Why Bates?

On Valentine’s Day, as the Bates Admissions staff is halfway through reading, re-reading, and re-re-reading every one of a record 4,506 applications for the Class of 2009, the topic of conversation in Lindholm House is the courtship between applicant and college.

For starters, the College expects a certain love light in the eyes of each student who applies. “We want people who want to be here, who have a passion for Bates,” says Jared Cash ’04, assistant dean of admissions.

Dean of Admissions Wylie Mitchell says that “we try to give the advantage to the applicant and put as many people as possible into our competition.”

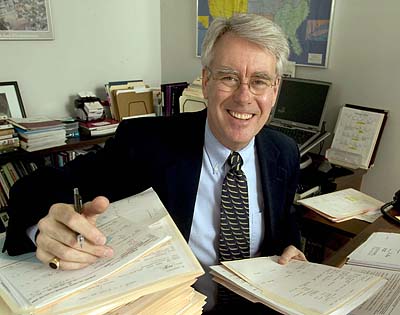

“All things being equal, we want someone for whom Bates is at the top of their list,” adds Dean of Admissions Wylie Mitchell, who has been at Bates since 1978, four years before Cash was born, and has served as dean since 1995.

Bates wants to be wooed, but the College is also a demanding suitor. The incoming class must number about 500 students evenly split between men and women, who represent worldwide human diversity, and also display the talent and proclivity to sustain 31 varsity sports, 89 clubs and activities (including art, dance, debate, theater, and music programs), and 32 academic programs.

So while mutual attraction is the ultimate goal, the process is also a “competition,” Mitchell says, and for every acceptance letter mailed, the College sends three letters of rejection. This is what makes the admissions courtship an angst-filled affair for applicants and parents: the 3-to-1 odds against acceptance, never mind the stories in the media that depict the process as something more perilous than Shackleton’s South Pole adventures.

Consider the numbers:

4,506: the grand total of Bates applications, counting Early Decision (472) and Regular Decision (4,034);

216: students accepted from Early Decision (they must matriculate);

1,035: students accepted from Regular Decision, of whom about 300 will choose to attend Bates (students typically are accepted by several colleges);

500: the target for the incoming class.

As with any courtship, the final result, however magical, defies easy explanation. Associate Professor of Biology Joe Pelliccia is serving as a faculty fellow in admissions in 2004-05. In late winter, he gathered with eight other admissions deans around a well-worn wooden table (a relic from Coram or Hedge, says Mitchell) for the discussion, debate, and decision on every applicant, whose credentials are reviewed three different times in the weeks leading up to committee meetings.

“What was heartening was to see that, when all the data was in front of you” — the application, essays, grades, SATs if provided, recommendations, interview reports — “most decisions were pretty straightforward,” Pelliccia says. “For those cases that were on the fence, I was impressed that everyone’s voice mattered.” President Hansen, who sat in on one morning session, also noted the “painstaking” care given each application.

Pelliccia captures the complexity — data and voices — and the Bates process, beginning with the interview, pays more attention to the voices. For instance, Bates is the rare college whose deans interview students both on campus and off, the latter during the fall season when they fan out across the country (visiting two dozen states during the campaign) and the world. Alumni-in-Admissions volunteers help out, too, and they conducted 541 interviews off campus this past cycle.

While many selective colleges conduct interviews (policies vary greatly), few value the one-on-one discussion as much as Bates. “At a college that supports the individual through all four years,” Mitchell says, “it seems straightforward that when you enroll 500 new students you would want to meet as many of those people as possible, going as far as three or four continents to do so.”

The primacy of the interview is reflected by a telling sentence that’s been in the Bates admissions Viewbook, unchanged, since the 1980s: “Candidates without an interview may be placing themselves at a disadvantage in the evaluation process.”

Says Mitchell, “It’s the most significant instruction that Bates gives prospective students.” The numbers bear him out. Only 13 percent of applicants who do not interview are admitted. Applicants who do interview are admitted at a 44 percent clip.

Besides being a vehicle for Bates to get to know an applicant (more later), the interview is a tool to keep the student front and center in the process. “When I meet prospective students here in the lounge at Lindholm House,” notes Mitchell, “it tends to be a conversation with the parent, with the student observing. In the interview, the student gets into the conversation.”

To give students more opportunities to be part of the conversation, Mitchell instituted a novel practice: split campus tours, where parents are led by one guide and students by another. Success begets success, and during the split tours prospective students can interact with charismatic Bates student tour guides. (The split-tour practice was quickly chronicled with approval by Jay Matthews in The Washington Post.)

These tricks of the trade have a greater purpose — “the dignity of each individual,” in the words of the Bates mission statement, the very basic College ethos that also led Bates to abolish SAT requirements in 1984, believing, and ultimately proving, the test to be a questionable predictor of academic success. This ethos is also reflected, less famously but just as importantly, in a modest plaque in Lindholm House honoring namesake Milt Lindholm ’35, dean emeritus of admissions. “You looked beyond the credentials and saw the person,” the plaque says.

In late winter the deans peel back the layers of credentials during committee deliberations. Optimism rules. “Bates admissions has always had a policy of hopefulness,” says Ginny Harrison ’63, longtime associate dean of admissions who retired in 2004. “It’s the same upbeat attitude about people that the College as a whole has.” As Mitchell likes to say, “We are not an office of rejection but an office of admission.” It sounds like a catch-phrase — after all, Bates mailed more than 3,000 letters of rejection this year — but Mitchell points out that “Bates ‘reads to admit,’ meaning we try to give the advantage to the applicant and put as many people as possible into our competition.”

For example, the subtle arrangement of paper in a Bates applicant’s manila admissions folder — the paper trail reflecting the applicant’s journey through high school to the cusp of college — suggests how Bates admissions reads to admit. Some schools put SATs and other test scores first. “Some offices are driven by their average SAT profile,” says Mitchell. “As an applicant, I would be afraid that if a folder starts with test scores, that would determine how thoroughly the folder is read.”

In a Bates admissions folder, in contrast, the reader sees applicant-created materials first: the application and Bates supplement, the essay, and other personal materials. “We read these materials first and ask, ‘Who is this person? What do they do? What do they offer? How do they think?’” Mitchell says.

Many schools require applicants to fill out a supplement to the Common Application, often asking for additional writing samples. Here, Bates poses a deceptively simple question: “Why, in particular, do you wish to attend Bates?” The query is another way, along with the interview and a campus visit, for Bates to know whether a student is truly interested or merely playing the field. Because half of all applicants apply to five or more colleges, and 10 percent apply to 11 or more schools, colleges like Bates increasingly measure applicant interest. In fact, every official contact a student has with Bates is chronicled in the admissions folder.

The middle third of the folder includes test scores — if submitted — as well as grades and recommendations. High grades in tough courses are expected; students who submit SATs need to know that Bates’ median is 1350 (out of 1600, though the new writing component will make the top score 2400). The student’s intellectual promise is assessed. “You never know 100 percent what’s being said in a recommendation,” Mitchell explains. “But a string of phrases like ‘hard worker… nice… consistent… always does well,’ may not suggest an applicant who delves beyond what’s at hand.”

The final item in the folder is the interview report, an all-important bookend.

Yet for all its importance, the purpose of the interview is sometimes misunderstood. When Mitchell educates new staffers, senior admissions fellows, and Alumni-in-Admissions volunteers, he tells them “not to think of the prospective student as a potential friend, a roommate, or a teammate. Admissions professionals are interested in the breadth of interests that students have. We are not simply drawn to people we like. We listen, but don’t judge.”

Harrison suggests that the applicant just try to “be yourself” in the interview. “Get beyond the pat answer. Don’t try to say what you think we want to hear.”

“For the successful candidate, the interview report should confirm all the other evidence in the folder,” Mitchell says. “That evidence needs to tell us that the applicant represents the best of Bates: talent, independence, motivation, and a desire to make connections with the world.”

Like a pitcher who goes to his best pitch in a tight spot, the committee relies on the basics — applicant interest and compatibility — when decisions are close. The valedictorian from a tiny Maine high school who gets a good interview report and whose sibling is an alum is admitted. (At Bates, as at other selective schools, applicants’ family relationships to Bates are considered — especially in the case of “legacies,” children of alums. Typically, 20 to 25 legacy students enroll each year from an applicant pool of about 50.) Yet, the applicant who wants Arabic and business courses and expresses worries about the senior thesis in the interview goes on the waitlist.

Still, there’s no glee, à la American Idol, when a folder goes into the deny box. “Who doesn’t get admitted to Bates?” repeats Cash, a Maine native. He shrugs. “A lot of great kids.”