King Day keynote looks at Mays '20 and his hopes for integrated church

Martin Luther King Jr. Day keynote speaker Barbara Savage at the podium in the Olin Concert Hall.

“Can we keep the faith when our dreams are imperfectly realized? I hope that we can.”

Monday was an especially fitting day for this question posed by historian Barbara Savage as she concluded her keynote speech for Bates’ Martin Luther King Jr. Day observances. The unifying theme for this year’s day of special programs was “Faith and Ethics in the Public Sphere: What is the Dream?” Savage’s address looked hard at a dream that Benjamin Mays ’20, the theologian, mentor to King and civil rights leader, had all his life: that the church could model integration for U.S. society at large.

Mays’ dream was not realized, leading to Savage’s expression of hope for faith’s power of endurance. That sentiment would resonate under any circumstances, but on this snowy Monday at Bates, where everyone was sobered by the tragedy of the Haitian earthquake, Savage’s closing was especially poignant.

Haiti, in fact, claimed an unbilled spot on the keynote presentation agenda, which was attended by about 200 people in the Olin Arts Center Concert Hall and opened by music from the Bates Jazz Band. Sophomore Eric Mathieu, who lives in New York state but has relatives in Haiti, made an appeal for disaster relief funds

- Read student impressions of King Day programming at Bates.

- See a multimedia presentation about Martin Luther King Jr. Day 2010 at Bates:

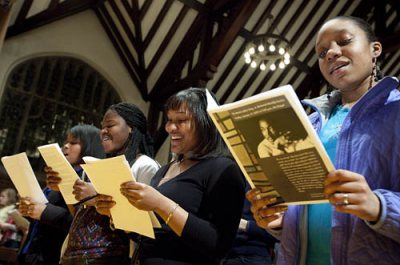

Amandla! sponsored the workshop “21st-Century African American Leadership.”

that raised $850 on the spot. (Other collections during the two-day King observance raised the total to more than $2,100, according to the Multifaith Chaplain’s office.)

Savage, a historian and the Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought at the University of Pennsylvania, spoke after remarks by Bates President Elaine Tuttle Hansen and Dean of the Faculty Jill Reich. Titled “Benjamin Mays and the Politics of Black Religion in the Age of Desegregation,” Savage’s address used Mays to illustrate some of the historic forces that helped shape, and constrain, the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century.

Inspired, in part, by extensive travels abroad, Mays believed that a racially integrated American Christian church could point the way to integration in the political and social spheres as well. Savage showed how Mays’ encounters with theologians and philosophers outside the U.S. — Gandhi, Muslim critics of Christianity, the would-be utopians of the 1937 Oxford Conference — shaped and annealed this ideal.

As a Southern, black, religious liberal, Savage explained, Mays had a complex case of the kind of “multiple consciousness” developed by people who live in worlds that do not overlap. “Perhaps the advantage of a multiple consciousness is a learned aptitude for abiding with irreconcilable contradictions,” she noted.

So even as Mays witnessed and advocated for a worldwide religious movement for social justice and racial integration, he understood that churches in the United States — which above all express the attitudes of their parishioners, both black and white — might stubbornly choose to remain segregated.

“He argued that Christianity ought to be color-blind and desegregated,” Savage said, “while at the same time he adhered to a belief in the political necessity of black-controlled institutions, especially churches and colleges.”

Ultimately, the contradictions prevailed. If the 1960s offered “a glimpse of the possibility of realization” of Mays’ dreams and ideals, Savage said, the last years of his life were marked mostly with personal disappointment and disillusionment about the goal of integration, especially in terms of black cultural and political identity. The trouble with integration, he told one audience, is that “it always moved from black to white and never from white to black.”

Citing Martin Luther King’s observation that among churchgoing Americans, 11 o’clock Sunday morning remains the “most segregated hour in this nation,” Savage noted that the ” ‘race church’ remains a fact of American life” and Mays’ “search for a progressive politics of religious globalism remains as elusive as during his long life.”

So if Mays’ adherence to these ideals represents a particularly American optimism, a faith in democracy and progress, as Savage suggested, this chapter of Mays’ story is nevertheless more of a cautionary tale.

As she said in her conclusion, “All of this is evidence of the necessity to shift and rethink our own dreams and our own ideas, and to realize that dreams are often incompletely and imperfectly realized.”