‘Love drug’ oxytocin’s possible dark side is the topic of $300,000 Bates study

Associate Professor of Psychology Nancy Koven works with Jason DeFelice ’17 of Salem, N.H., and Julia Rice ’16 of Providence, R.I., to analyze brain images during their cognitive neuroscience class on Sept. 24, 2015. (Josh Kuckens/Bates College)

“I want a new drug,” Huey Lewis sang in the ’80s, “one that makes me feel like I feel when I’m with you.”

That drug might be oxytocin. Released by our brains when we get physically or emotionally close to someone, the hormone is associated with nurturing and intimacy — it’s even part of the feel-good feedback loop when dogs and humans gaze into each other’s eyes.

While the public has been told warm and fuzzy stories about the hormone’s effects, Bates neuroscientist Nancy Koven will use a three-year, nearly $300,000 federal grant to take a cold and hard look at oxytocin.

“Oxytocin in the media is the love hormone, the cuddle hormone. I see my project as probing its potential dark side,” says Koven, an associate professor of psychology, chair of the Program in Neuroscience, and recipient of a $299,439 grant from the National Institute on Aging within the National Institutes of Health.

Bates pilot study in 2013 yields “huge surprise.”

Koven got a glimpse of OT’s potential dark side in 2013 when she and a senior neuroscience major got a curious result from a pilot study: Otherwise healthy young subjects who had naturally high levels of oxytocin reported feeling anxious, socially disconnected, and aloof.

“It was a huge surprise,” she says.

At the time, Koven and her thesis student, Laura Max ’13, were looking to see if there was a relationship between low oxytocin levels and personality indicators of psychosis proneness.

“We didn’t find evidence of that,” Koven says, “but we did find a surprising opposite effect: Higher levels of OT can have negative emotional correlates.”

That wasn’t the only surprise. The subjects who reported those aloof feelings had also scored well on tests of emotional intelligence, including the ability to read people’s facial expressions and predict their emotions.

“The students who were innately good at that and who also had high OT levels were choosing to remove themselves from social settings,” Koven says.

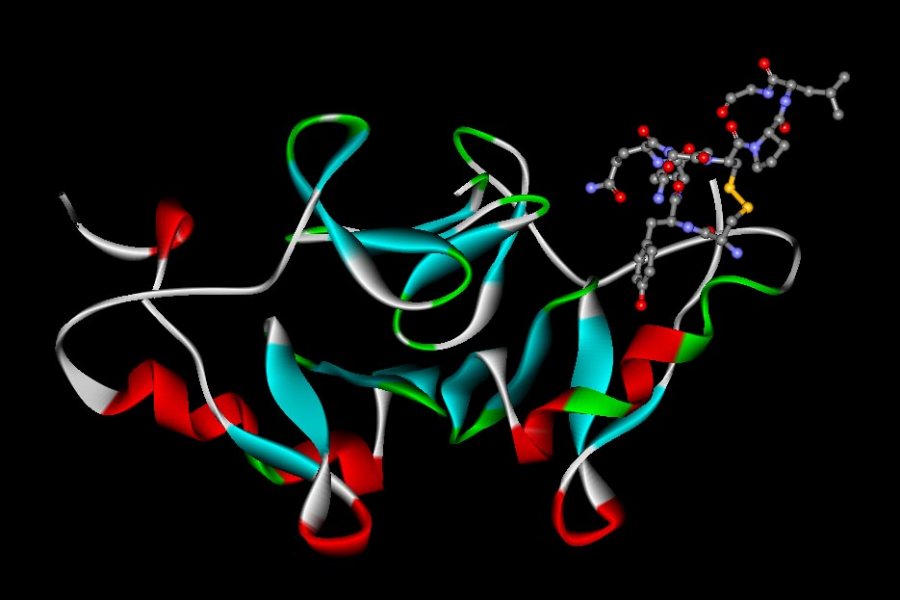

A representation of the oxytocin molecule, upper right, bound to the protein neurophysin, shown as ribbons, that carries it through the body.

Oxytocin is widely available, mostly as a spray, with one website suggesting that you spray it “on your shoulders like a perfume [and] let other people around you inhale it, thus making them more trusting of you.”

Another site says that “the potential benefits of this to your social and business life hardly need to be spelled out.” Koven spells it out. “I am very alarmed by that message. It’s being marketed as a thinly-disguised date-rape drug.”

“Maybe too much…is not a good thing.”

The haphazard use of oxytocin isn’t limited to the online marketplace. In at least one study, Koven says, oxytocin was administered to residents of a nursing home to boost their desire to socialize. “It had no effect at all — we’re not exactly sure why — but there seems to be a lack of understanding that maybe too much of this hormone is not a good thing.”

She adds, “If you keep giving this drug without measuring how much oxytocin is already in someone’s system, you don’t know what emotional and cognitive states you’re pushing people into.”

That will be a main goal of Koven’s study, which will involve 240 subjects from age 20 to 80, primarily Maine residents. She wants to learn more about patterns of psychosocial adjustment associated with our natural levels of OT. For example, she asks, “is someone with a high OT level becoming aloof because they don’t find socializing rewarding? Or because socializing is overwhelming, like hitting a raw nerve?”

Koven also wants to look at how OT plays out over adulthood. “While there is considerable literature describing age-related cognitive decline,” she says, “little is known about the effects of aging on the OT system.”

And, she wants to see if individual differences in cognitive and affective style — which themselves might be governed by two additional neurotransmitters, serotonin and dopamine — moderate the effects of OT on our sense of well-being.

It is easier to drool than to be poked.

The project’s final goal is less about OT itself than about how researchers do this type of work. Specifically, she wants to prove to the scientific community that a researcher can effectively use saliva, rather than blood, to test for trace amounts of a substance like OT.

Obtaining saliva “is much less invasive than blood. It’s easier to drool into a vial than to be poked with a needle,” she says. “If we want to increase OT research, saliva is the way to go. We need to raise the esteem of saliva.”

While blood is the “gold standard” when it comes to testing for substances flowing through our bodies, Koven hopes to show that a current biochemical technique, known as two-dimensional liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, can be used effectively on saliva, too.

The saliva tests will be done through a partnership with the University of New England.

As she does with all her research, Koven will enlist senior neuroscience and psychology majors as her research partners. This year’s team members are Zachary Radford ’16 of Wolfeboro Falls, N.H.; Sophie Sohval ’16 of Ridgewood, N.J.; Adriane Spiro ’16 of Durham, N.C.; and Erica Veazey ’16 of Fairbanks, Alaska.

Each will have the opportunity to publish aspects of the work both in their senior theses and in scholarly journals.

“Almost all my publications are with students because Bates students do the science with me. They are junior colleagues in a shared enterprise,” Koven says.

In 2013, for example, Max reported the surprise findings both in her honors thesis and, with Koven, in an article in the journal Psychoneuroendocrinology.

“When students join me in the lab, it becomes their research, too,” she says.

“As a faculty member, nothing is more thrilling than to watch students leap from being consumers of knowledge to producers of knowledge.”