Bates in the News: Feb. 26, 2016

Digital and Computational Studies

Bates exemplifies the way a college “whose main focus isn’t technology is adjusting to the times.” — Inside Higher Ed

Inside Higher Ed feature writer Carl Straumsheim notes that Bates is “one example of how a college whose main focus isn’t technology is adjusting to the times.”

Writing about the college’s launch of a new Program in Digital and Computational Studies, Straumshein says that Bates’ approach is distinctive in choosing an interdisciplinary approach, “framing computer science as a way to help faculty members in other departments introduce computing in their own courses.”

It is “incredibly important” for Bates to embed digital and computational thinking into the “context of the liberal arts.”

He quotes President Spencer, who notes that for Bates it is “incredibly important” to embed learning about “digital platforms, computational thinking, and the reality of digital connectivity” into the “context of the liberal arts.”

The story notes that Bates’ approach has a great advantage: It’s “paid for,” as the college is using $19 million in gift commitments “to hire six new faculty members, three of whom will shape the digital and computational studies program.”

Digital and Computational Studies, Part 2

Employers want skills that go beyond computers; enter Bates and the liberal arts — MPBN

As Bates integrate computational skills into a liberal arts framework, says a Maine Public Broadcasting Network radio story about the college’s new digital and computational studies program, its students will benefit in the job market.

Matt Auer is vice president for academic affairs and dean of the college. (Sarah Crosby/Bates College)

Reporter Patty Wight says that while “it’s no secret that when it comes to the current job market, employers are looking for applicants with strong computer skills,” they also want to see skills that go beyond computers.

Matt Auer, vice president for academic affairs and dean of the faculty, tells Wight about an entrepreneur who told him that many job seekers come up short.

The entrepreneur told Auer that “we don’t need people who can just write clean code.” Rather, the need is for “people who can solve problems. We need people who can develop apps that will be helpful to society or make people’s lives better.”

“Enter a liberal arts education,” says Wight.

Matt Bogyo ’93

A key breakthrough in the new fight against malaria — Chemical & Engineering News

The battle against malaria and mosquitoes has been going on for hundreds of years. This undated photo from the early 1900s shows a man in Panama spraying oil to control mosquitoes. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

There’s an urgent need for new drugs to fight malaria, and Matt Bogyo ’93 is providing the weapons.

Bogyo, a researcher at Stanford University School of Medicine, is part of a team that has found “a small molecule” that can kill the malaria-causing parasite in mice.

The findings were first reported in the journal Nature on Feb. 20 and outlined in a recent story in Chemical & Engineering News.

CEN reporter Stu Borman says that the molecule does its thing by “inhibiting the proteasome, the cell’s protein-degrading machine in the parasite while doing less damage to the host.”

These “selective proteasome inhibitors,” Borman continues, “could complement current antimalarial drugs and lead to medications for other infectious diseases.”

Bogyo, a professor in the Department of Pathology at Stanford, “is doing absolutely amazing work,” says his honors thesis adviser at Bates, Dana Professor of Chemistry Thomas Wenzel.

Josh Macht ’91

Leading a “trend-defying 21 percent surge in paid circulation” at Harvard Business Review — The Boston Globe

Harvard Business Review’s group publisher Josh Macht ’91 and editor-in-chief Al Ignatius have done more than drag the HBR into the 21st century, reports The Boston Globe.

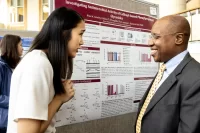

Joshua Macht ’91 meets with Shaina Lam ’17 of Portland, Maine, during a visit to Bates as part of the college’s Purposeful Work initiative.

(Sarah Crosby/Bates College)

They’ve done what other magazines have not: achieved a “trend-defying 21 percent surge in paid circulation from 2010.” The magazine’s 286,000 subscribers are at “the highest level in its history.”

Ad revenue has plummeted, as it has at most publications, but unlike others, digital sales have more than made up for the loss.

Jackie Ordemann ’15

The mark that lead leaves on the brain might show up as people age. — Science News

Using the water/lead crisis in Flint, Mich., as a backdrop, Science News points to new research by Jackie Ordmann ’15 and her thesis adviser, former Bates chemistry professor Rachel Austin, that suggests how lead could play a part in schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s.

Lead has the potential to “disrupt optimal neurological functioning” in both children and older people, according to new research by Rachel Austin and Jackie Ordemann ’15. (Photo courtesy of images-of-elements.com)

In the case of brain diseases, lead might “do its dirty work” by “masquerading as zinc,” says reporter Meghan Rosen.

Zinc, a trace element in human physiology, serves to “anchor floppy sections of protein together, forming a shape that plugs into DNA. This lets proteins flip genes on and off like a light switch.”

In the Jan. 8 issue of the journal Metallomics, Austin and Ordemann suggest that when lead takes the place of zinc, the protein switch might not work the same way.

Known as “lead substitution,” it has “the potential to disrupt optimal neurological functioning during development and much later in life,” say the authors.

In Flint, the city introduced a new, more acidic water supply from the Flint River that stripped away the protective scale that had built up in old lead pipes, allowing lead to leach into the water supply.