As the Bates community far and wide learns about the historic $50 million gift from Michael ’80 and Alison Grott Bonney ’80, there’s one reaction the Bonneys are hoping for.

“We hope people think, ‘Wow. There’s something special about Bates College, and I want to be a part of it,’” says Michael.

“We have never been more optimistic about the future of Bates.”

One of the largest monetary gifts ever to a Maine college, the Bonneys’ gift will support new and modernized STEM facilities at Bates, an essential part of the Driving Academic Excellence priority of the $300 million Bates Campaign.

Given to Bates by the Bonneys’ family foundation, the gift supports an equally historic fundraising effort. The Bates Campaign is the largest in Bates history and, in keeping with Mike and Alison’s hopes, one that’s been joined by many partners: The campaign kicked off this week with $168.5 million in gifts to date.

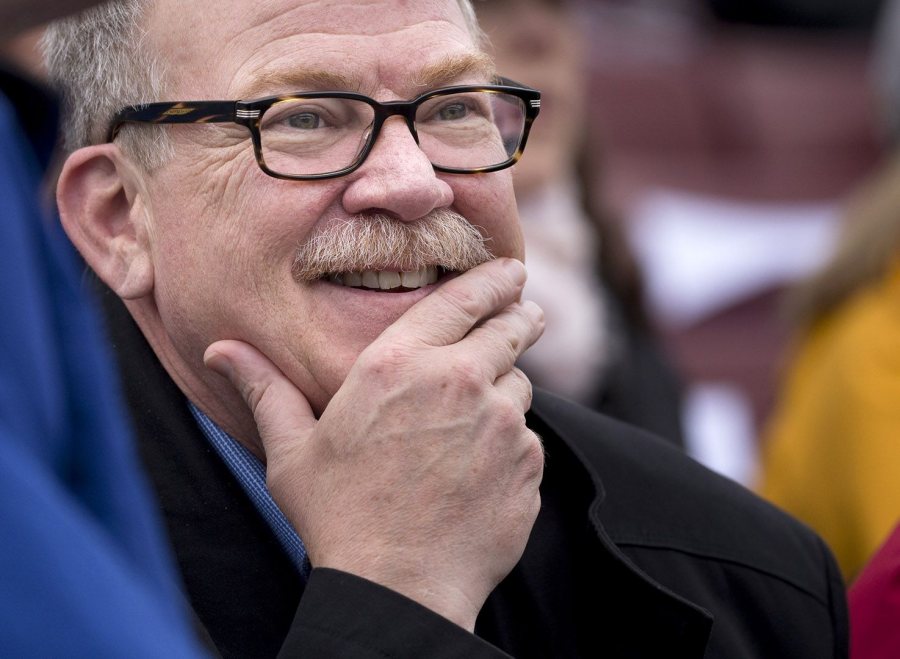

Mike Bonney ’80 and Alison Bonney ’80 talk about their $50 million gift to Bates during Tuesday night’s Bates Campaign kickoff in Boston. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The gift is singular, yet the Bonneys’ motivation for giving — gratitude combined with come-one, come-all optimism — is shared by the community of alumni who love and support Bates.

“Alison and I are incredibly fortunate to have been associated with this institution for the vast portion of our lives, more than 40 years,” says Mike Bonney.

“At the same time, we have never been more optimistic about the future of Bates and its ability to adapt, thrive, and continue to prepare our students and graduates to navigate the world in a purposeful and joyful way.”

Two of the four Bates generations of the Bonney family are seen here. At right are Mike ’80 and Alison Bonney ’80, and at left are Weston Bonney ’50 and his wife, Elaine Bonney. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

As with many in the Bates community, the Bonneys’ love for the college is seen in a rich tapestry of personal relationships.

The weave starts with family — four generations’ worth. Mike’s maternal grandfather, Lauren Gilbert, was a member of the Class of 1927 who was born and lived in nearby Turner. “He was a student when Alumni Gym was built,” says Mike, whose father, “Wes” Bonney, graduated in 1950 and is a trustee emeritus.

Mike and Alison met during their first year at Bates, and their college circle of friends remains tight-knit today. “My closest friends today are friends that I met at Bates,” he says. One of his three sisters, Melissa Bonney Kane, graduated in 1981, and Mike and Alison’s three children graduated from Bates, in 2009, 2012, and 2015.

Mike is chair of the Bates Board of Trustees, co-chair of The Bates Campaign, and the retired CEO of Cubist Pharmaceuticals.

He led Cubist to the most successful U.S. launch ever of an important intravenous antibiotic, Cubicin, and the acquisition of two firms. In 2011, he was named one of the six best corporate leaders in the country by MarketWatch. He retired in 2014, the year Cubist was acquired by Merck & Co.

Early in his career in Maine, Mike managed a Wellby’s drug store in Bangor, a chain once operated by Maine-based Hannaford Brothers. As he told NECN’s CEO Corner in 2011, he found himself wanting to learn about the pharmaceutical side of the business. “I found I spent a lot of my time in the pharmacy asking the pharmacist, ‘What’s this used for, what’s that used for?’”

He’s never abandoned that curious, inquisitive style.

“I ask a lot of questions,” Mike says. “I am a lifelong learner and I love to learn new stuff. I will dive into any subject matter even though I have no reason to expect that I can learn it. And I try to figure out what it all means.”

Bates, he says, taught him how to “tease out, amongst a broad array of information, the things that are particularly germane to a specific issue or solving a specific problem.”

Mike recently talked about what The Bates Campaign means for Bates and about his and Alison’s gift to the college.

In a way, college fundraising campaigns are similar. You tend to raise money to support students, the faculty, and facilities. But every campaign also occupies a specific time and place for the institution and in the world. How is The Bates Campaign distinctive?

The pithy answer is that the time is now. What I mean by that — at least in the trajectory of my relationship with Bates — is that never have both the external and internal forces aligned to make a campaign more critical, but also more joyous, than this one.

We have an incredible set of forces working on the world today — some threatening — that are changing the way we interact and changing with whom we interact. Because of that, I believe that never in the history of the liberal arts tradition has a liberal arts education been more critical, when one thinks about the future of our society, than today. That’s the external piece.

The internal piece of this is that it is very clear to me that under Clayton Spencer’s leadership we have developed a tremendous amount of forward momentum. She has built a superb administrative team to complement what I believe to be the most dedicated and hard-working faculty in higher education.

The residential liberal arts model is an enduring model, but it is not a static model.

We have a clear vision for how the liberal arts education needs to evolve to provide our students and our graduates the skills and the discipline of learning that will not only serve them as they build their lives beyond Bates but, importantly, allow them to navigate what is an increasingly complex and, to use a science term, fractionated world.

How central is the concept of innovation to this campaign?

Different times require different skills from citizens. The residential liberal arts model is an enduring model, but it is not a static model.

Along with the digitization of the world, the creation of knowledge now more than ever ignores traditional departmental or disciplinary boundaries. With innovation, you enable the institution to evolve its pedagogy in a way that remains true to the ideals of the liberal arts but relevant to the skills that the students need.

Through innovation, we ensure that students continue to develop the habits of mind they need to navigate this amorphous world — where every day more and more boundaries come down — with greater clarity and greater confidence.

Given our distinctive history, we need to stay true to the founding values we’ve tried to live up to for the last 160 years and also be forward-looking, to anticipate where knowledge is going, where society is going, and how we can best prepare our students to navigate the world in a purposeful and joyful way.

In what ways has Bates stayed the same? What does your dad recognize about Bates today?

Our strong sense of community is an enduring legacy, as is our aspiration to be a welcoming community to a diverse group of students, faculty, and administrators.

I also think that the Bates idea that success is defined by elevating the community, that it is not a zero-sum game, remains strong.

And the warmth of the place has endured since Dad was here in the late ’40s. I’m sure it was resonant before that, but that’s as far as my institutional memory goes — I don’t remember having conversations with my grandfather about his experiences in the 1920s!

![Students get their mail in Chase Hall this 1950s photograph. Then and now, "the warmth of [Bates] has endured since Dad was here," says Mike Bonney. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2017/05/web-4-E-14-postoffice-2-900x717.jpg)

Students get their mail in Chase Hall this 1950s photograph. “The warmth of [Bates] has endured since Dad was here” in the late 1940s, says Mike Bonney. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

What does Bates look like after this campaign?

I hope it looks like a college on the move. Like we’re taking on the tough questions of what skills our graduates need — as we always have done — and we’re able to adjust our offerings to ensure students have every opportunity to acquire and demonstrate those needed skills before they leave.

I hope we’re able to take even greater pride in the institution going forward but that it remains recognizable to our longest, “most experienced” alumni!

Why is Clayton Spencer the right president for Bates at this time?

She is visionary and a tremendous integrator. She sees the forces shaping our society and she sees the globalization of everything.

“We are incredibly fortunate to have Clayton Spencer at the helm in this moment in history,” says Mike Bonney. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Clayton also has a deep and intuitive understanding of what the mission of the liberal arts has been historically, so she is able to articulate how we can stay true to our traditional values while evolving and staying at the forefront of the residential liberal arts experience. We are incredibly fortunate to have her at the helm in this moment in history.

As the retired CEO of a major pharmaceutical company, you probably have a pretty good grasp how trends in STEM intersect with Bates’ needs.

For me, the driving force is how we ensure that all students who graduate from Bates have the foundational skills to pursue a career in the sciences if that is their interest. Almost by definition, that requires that they have first-class training so they can get into the best Ph.D., medical, or other programs in the country.

It is also clear to me in the 21st century — and this is very relevant to the work I do in life sciences in the commercial space — is going to be the century of biology.

One of the challenges we have as we think about the sciences for the 21st century is how we create physical spaces that will work for what is foreseeable — and also work for what is not foreseeable.

Our understanding of how humans work and how disease processes manifest themselves — the genetic components and the environmental components, for example — is going to explode. We can sequence the DNA of any living organism and start getting insights into how that organism evolved, where those genes came from, and what function they have. It’s remarkably different today than it was just 10 years ago, let alone 60 years ago.

It is an incredibly exciting time. And we need to make sure that our faculty and students have the skills and tools to be active participants in this explosion of understanding.

In terms of facilities, how can we better support our faculty in the sciences?

Bates has a very strong faculty overall. In the sciences, as with other divisions, a lot of the work is at the intersection of traditional disciplines. But our facilities don’t support the ability of the various disciplines to collaborate, either in their pedagogy or their research.

Improved STEM facilities are an area where we can see dramatic gains not only in the experience of our students but in the continued recruitment of world-class researchers as Bates professors in the sciences.

Assistant in Instruction Greg Anderson works with biology major Ruth van Kampen ’19 of Brunswick, Maine, in the Laboratory for Advanced Microscopies in Carnegie Science Hall. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Then there’s an attendant issue: The tools that scientists use today are evolving at a relatively fast rate. One of the challenges we have as we think about the sciences for the 21st century is how we create physical spaces that will work for what is foreseeable — and also work for what is not foreseeable.

We know that the tools, techniques, and machines that we use to probe the world are going to be different. Inevitably, the pedagogy is going to be different. So we need to make sure that, however we envision our future scientific facilities, we retain lots of optionality to configure and reconfigure.

What qualities do you admire in our faculty?

I would have to start with their dedication to pedagogy. Their willingness to engage one-on-one with students beyond the classroom is unparalleled.

The other powerful aspect of our faculty is their ability to balance effective pedagogy with remarkable scholarship. When I think about how much energy they devote to coaching these young people, and then look at the output of their research, it is really quite remarkable.

They are grade-A players in their scholarly communities while being professors at a small residential college in Lewiston, Maine. That’s just great.

Where does athletics fit into the liberal arts model?

I take great pride in the athletic success of Bates students. To use this year’s men’s lacrosse team as an example, this is an extraordinary team that has brought great pride to the institution.

More broadly, I think that if our mission is to prepare students to go forth in the world and to build lives of purpose that have impact on their communities, one of the aspects of that is to develop the habits of the mind but also the habits of the body to remain robust for a long time. Sports is one way to do that.

“Sports is one way to learn to recognize different skill levels while still valuing what everyone brings to the team. And that’s a critical ability.” (Brewster Burns for Bates College)

Sports also teaches a set of skills that I think are increasingly critical. On a sports team, you need to figure out how, if your teammates approach the game differently, you can mesh as a team and make 11 lacrosse players better as a team than as 11 individuals.

Sports is one way to learn to recognize different skill levels while still valuing what everyone brings to the team. And that’s a critical ability if you are going to lead any large organization, a nonprofit, a community organization, or a Little League team.

You have asked for gifts on behalf of Bates. And you have been asked for gifts. What are those experiences like?

I would use the word “joyous.”

“Facilitating that personal journey of discovery for a donor is a very, very joyous thing,” says Mike Bonney. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

But perhaps more important than the gift solicitation is the process that leads up to it. What you’re trying to do in the process is to find where the donor’s passion intersects with the priorities of the institution. When you can find that intersection and make that connection, it is magical.

It is a great joy to be in the position to be a philanthropist. But not everyone is completely comfortable with what that means. They’re not sure how to go about discovering their passion and where their philanthropic dollars can have an impact that is meaningful to them.

Facilitating that personal journey of discovery for a donor is a very, very joyous thing.

Can you talk about the alignment of a campaign priority with your own background, experiences, and family?

Alison and I have been very fortunate in so many ways. We never anticipated that we would be in a position to be philanthropists at the level we are.

We always, however, had a strong belief that we had an obligation to improve the communities in which we have lived and to ensure that subsequent generations had the kinds of opportunities we had both professionally and personally.

We found each other at Bates. Our closest friends are Bates friends. We started our life together feeling that life was a great adventure, and it has taken us places we could never have predicted. Along the way there are always bumps on the road, but we try to maintain an optimistic outlook — a continued commitment to each other, to finding joy in the world, to being optimistic about the world.

“I am absolutely convinced that the world is a better place when we put 500 Bates graduates out into the wider world every year.”

All that has put us in a place that is humbling, in many ways, to be able to help provide opportunities for the next generation and generations after that to build the kind of lives they hope for.

Does your gift reflect optimism or does it help create optimism?

I hope both. I really do. I am very optimistic about the future of this institution. Beyond the optimism, I am absolutely convinced that the world is a better place when we put 500 Bates graduates out into the wider world every year. From that standpoint, our gift reflects optimism.

But I also hope — and Alison and I have talked a lot about this — that by coming forward with a gift like ours, at this moment in time, and being willing to own that gift, that we will inspire others within our community to see the possibility that the future holds for Bates and its community if we are all thoughtful about our philanthropy.