Sculptor Rona Pondick and painter Robert Feintuch have been an item since 1975, and have been notable presences in the art world since the ’80s.

Painter Robert Feintuch and sculptor Rona Pondick pose with some of their work at the Bates College Museum of Art. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

But only since February 2017 has it been possible to see a substantial selection of both their work combined in one exhibition. And only now has that exhibition come to Bates, where Feintuch is in his 42nd and final year on the art and visual culture faculty.

Opening with a 6 p.m. gallery talk and reception on Oct. 27 at the Museum of Art, the exhibition Rona Pondick and Robert Feintuch: Heads, Hands, Feet; Sleeping, Holding, Dreaming, Dying was organized by museum director Dan Mills and made its debut nine months ago at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art.

“Rona and Robert each use themselves as a model, yet neither makes self-portraits per se,” Mills says. “While their work is materially very different, this approach to making work and the psychological interest in the body and gesture that they have in common fascinated me.

“I started thinking about exhibiting their work for Bates, where Robert has taught for many years but rarely shown and where Rona has never shown. And as I was developing this idea, I realized that no one had ever organized an exhibition investigating” that common interest.

“It became clear that this is the exhibition we should present at Bates.”

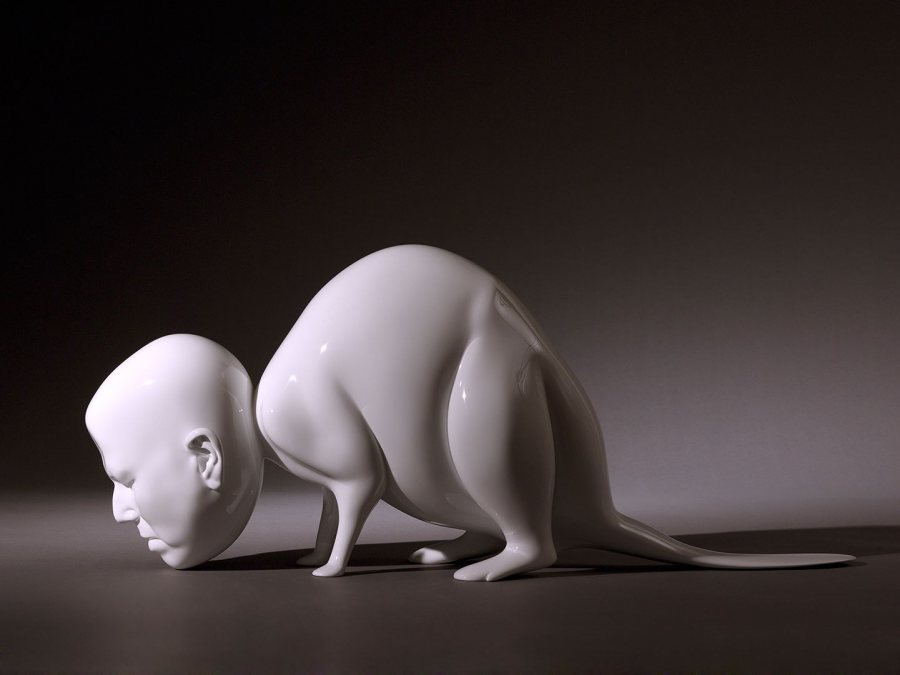

“White Beaver” (2009–11) by Rona Pondick, painted bronze, edition 2/3. Courtesy of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London/Paris/Salzburg; Sonnabend Gallery, New York; Howard Yezerski Gallery, Boston; Zevitas/Marcus Gallery, Los Angeles; and the artist.

Until Mills proposed the idea a few years ago, Feintuch and Pondick hadn’t considered a joint exhibition — even though each is intimately familiar with the other’s work (they even had adjacent studios for many years).

“A few people who followed our work very closely talked about seeing relationships between the work,” says Feintuch. But, he continues, “on a superficial level, we kept seeing the differences.”

Mills was one of the ones who saw the relationships. “They believe the body speaks,” he says. “They seek to represent subjective experience and psychological states through a physical vocabulary comprising aspects such as gesture, posture, naturalism, and expressive distortion.”

Pondick’s sculptures combine forms from the human body — usually her own — with those from non-human animals. ARTnews critic Lilly Wei ascribed “disquieting psychological reverberations” to her sculptures, reverberations that “paradoxically attract and repel.”

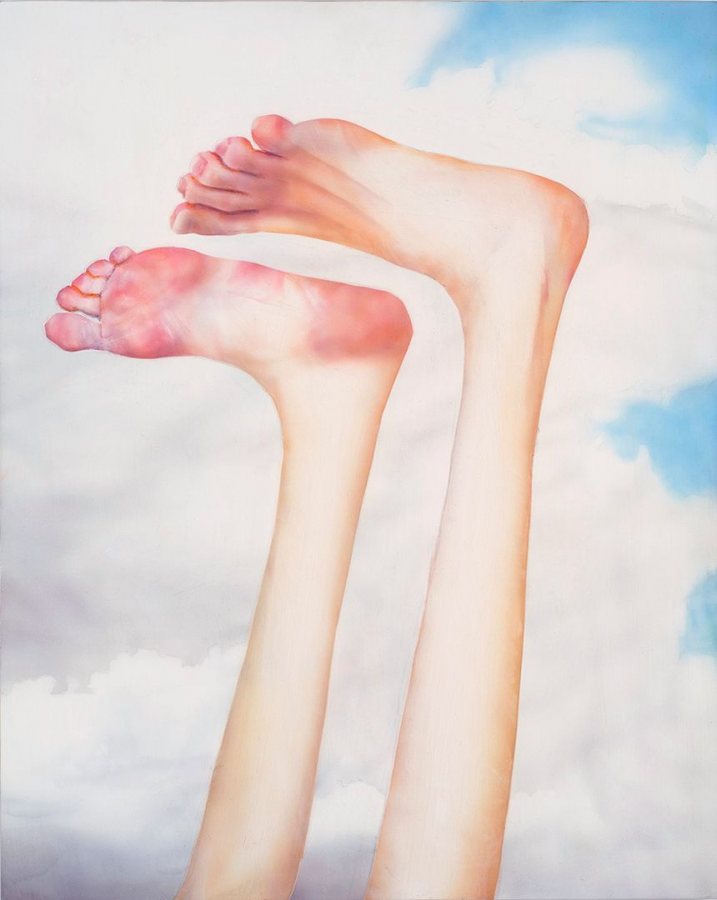

Feintuch, meanwhile, situates unheroic older men in dreamlike settings that express vanity and vulnerability, and his work is consistently regarded as comic and rooted in psychological machinations.

“Feet Up” (2013) by Robert Feintuch, polymer emulsion on honeycomb panel. Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery, New York; Howard Yezerski Gallery, Boston; Zevitas/Marcus Gallery, Los Angeles; and the artist.

Now residents of New York City, they met at the Yale University School of Art. The Bates exhibition comprises nine sculptures and a series of prints created by Pondick between 1998 and 2013, and 11 paintings that Feintuch made between 2007 and 2016.

Juxtaposing their artworks was something of a revelation to the couple. “One of the things that we’ve both been really struck by, between installing the show in Utah and then again here, is that it feels like our work goes together in a very interesting way,” says Pondick.

“Even though the work is approached so differently and our sensibilities are so different, we share so many interests that we complement each other in ways that are surprising to us. And that is both shocking and kind of intriguing,” given how long they’ve been together.

“We’re both interested in having people interpret the work,” says Feintuch — that is, look beyond the physical presence of a given piece. “That physical presence makes a lot of the meaning, but we also want people to think about what the work is about and what it feels like psychologically.

“I’ve had a wide range of interpretations of my work across the years, and none of them seem wrong to me. A lot of visual art is ambiguous in its meanings, and it’s one of the things I love about it.”

Art-historical references lend another dimension of meaning to their work. Pondick’s animal/human hybrid sculptures have a long lineage across many cultures, and Feintuch’s paintings often play with historical mythological and religious imagery.

Similarly, each combines age-old and cutting-edge technologies. Pondick employs three-dimensional scanning, computer imaging, carving, hand modeling, and traditional metal casting. Feintuch’s preparation for a painting has often mated hand-drawing from life with drawing on the computer and manipulating photographic material.

“Marmot” (1998-99) by Rona Pondick, silicone rubber, exhibition copy, edition of 6. Courtesy of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London/Paris/ Salzburg; Sonnabend Gallery, New York; Howard Yezerski Gallery, Boston; Zevitas/Marcus Gallery, Los Angeles; and the artist.

“Feintuch’s a terrific painter, whatever the subject,” Cate McQuaid wrote in a 2012 Boston Globe review. His works “wrestle with the debilitations and humiliations mortality imposes on us, but also with the possibility of grace, which we find in beauty and in hope.”

Reviewing “Heads, Hands, Feet” for Salt Lake City’s SLUG Magazine, Kathy Zhou wrote that Pondick recognizes the viewer’s “tendency to search for artworks’ distinctly human elements, and she embraces it, toying with the human form and the psychological themes it evokes in her audience.

“Her resulting sculptures are at times fantastical, at times unsettling and thoroughly difficult from which to avert your gaze.”

“Fat Hercules” (2011) by Robert Feintuch, polymer emulsion on honeycomb panel. Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery, New York; Howard Yezerski Gallery, Boston; Zevitas/Marcus Gallery, Los Angeles; and the artist.

Feintuch is a senior lecturer in the art and visual culture department. It’s fitting that he’s taking part in a Bates exhibition himself during his final year as an active faculty member: Since he began at Bates, in 1976, he has advised studio art majors as they spend their final year at Bates making work for the annual Senior Thesis Exhibition. (For many of those years, Associate Professor Pamela Johnson has advised the seniors during the fall semester, and Feintuch during the winter.)

Pondick has co-taught with her husband at the International Summer Academy of Fine Arts, in Salzburg, Austria. “I’ve witnessed how easily Robert can connect in a very quick way with a student,” she says, “understanding what they should be looking at and asking them questions, so that they can start asking the questions that you need to ask when you’re in the studio alone.

“And it’s not easy to forget about your own prejudices and the way that you think, and say, ‘This is not the way I think, but how would I approach this?’ So that you can then help your students develop.”

“Which is one of the pleasures of teaching,” Feintuch responds. “It’s fun doing that.”