When the time came for the students and professor in the upper-level course “Film Festival Studies” to produce an actual festival — the inaugural Bates Film Festival — there were friends ready to lend a hand.

Friends like Academy Award–winner Stacey Kabat ’85, Anike Tourse ’92, Nicole Danser ’15, Taylor Blackburn ’15, and Alexandra Morrow ’16, all creators of short films that will be shown at the festival. And like Constance “Stanzy” Brimelow ’16, who, as an associate producer of a Sundance award–winning film, will take part in a festival panel on women in media.

Rhetoric professor Jon Cavallero leads his “Film Festival Studies” class in Pettigrew Hall on March 19, two days before the opening of the Bates Film Festival. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

And Trey Callaway P’20, a prominent producer and screenwriter who will lead a screenwriting master class on the festival’s final day. And Michael Sargent, a Bates psychology professor whose filmmaking debut has its premiere at the festival: Witchcraft Blue, a feature-length documentary about burlesque performers in Maine.

The willingness of these folks to work with the 14 “Film Festival Studies” students as they organized the BFF exemplifies a collateral benefit of the Bates education. Rhetoric professor Jonathan Cavallero opened the Bates network of industry contacts, many of whom he has met or taught since coming to campus in 2013, to the class knowing that his students might benefit from those connections later on.

Even as the festival, and Bates’ overall exploration of film, is benefiting from them now. “Bates people who are in film want film at Bates to grow,” says one of Cavallero’s students, Luc Alper-Leroux ’20 of Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “So they did everything they could to help.”

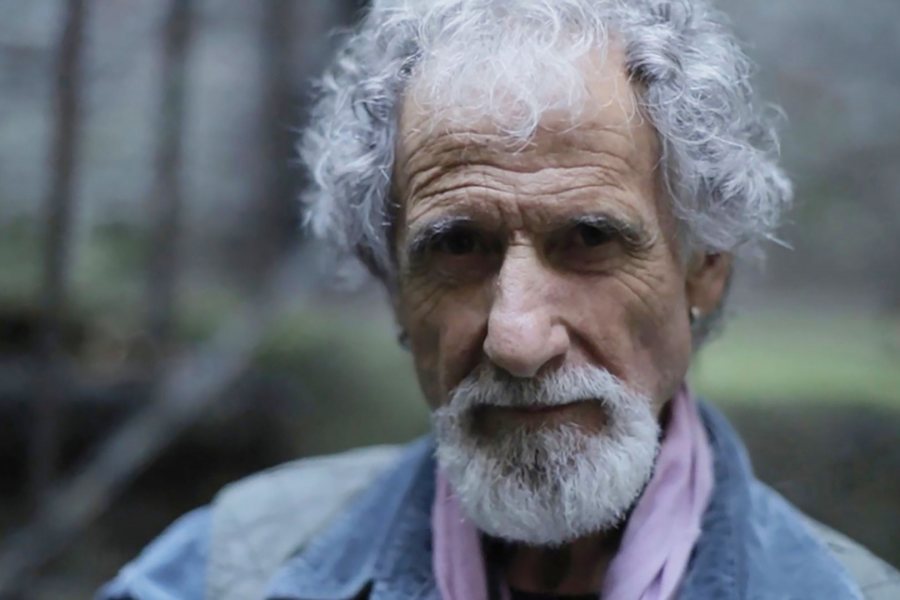

The Bates Film Festival features Frank Serpico, a documentary profile of the reform-minded undercover policeman whose story was fictionalized in a hit 1970s film, on March 23.

Another way the festival says “Bates” is through its spotlight on films involved with social and environmental justice. “That’s one thing that we really wanted to do with this festival,” says Nate Merchant ’18 of Los Angeles, a rhetoric major focusing on screen studies.

“With the overarching theme of social justice, we wanted to find different narratives that can influence people in powerful ways.”

While there are some exceptions on the screening schedule (notably the midnight screening of the 1998 teen thriller I Still Know What You Did Last Summer, written by Callaway), socially conscious films dominate the festival schedule. They delve into topics as timely as police misbehavior (e.g., Frank Serpico, a documentary profile of the reform-minded undercover cop); ethnic identities in the U.S. (White Rabbit, following the travails of a Korean American performance artist); and the consequences of rape (The Light of the Moon).

Clockwise from upper left, rhetoric professor Jon Cavallero is shown with some student organizers of the inaugural Bates Film Festival: Nathaniel Merchant ’18 of Los Angeles, Luc Alper-Leroux ’20 of Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Gillian Coyne ’19 of New York, and Marisa Sittheeamorn ’18 of Bangkok. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

Alper-Leroux adds that the class has sought out films that bring international perspectives to international concerns. For instance, he says, “we often talk about climate change, but it’s only ever within our context” as Americans. Hence the screening of Anote’s Ark, exploring the topic of climate change from the standpoint of Kiribati, an island nation that will likely be underwater within this century.

An afternoon session of short films by Bates alumnae and an evening screening of Witchcraft Blue open the festival on March 21. Sargent’s topic might seem lurid at first, but Cavallero points out that what the psychology professor is really examining is body positivity “and getting to a comfortable place with that.”

Cavallero explains, “These performers outwardly seem quite confident in their bodies, but Michael is able, through his interviews, to reveal that there’s an inner dialogue. It’s often a struggle for them to get on stage and perform.

“What I really appreciate about his film is that it reveals exactly how much his subjects trusted him” to reveal so much in a public forum. “It’s an impressive film, and very much is in line with what we’re trying to accomplish with the festival.”

The Bates Shorts session, meanwhile, exclusively presents work by alumnae. Among them are Tourse, who directed America; I Too; writer-producer-editor Morrow (The River Behind My House and The First Coast); Academy Award winner Kabat, producer of Strong at the Broken Places: Turning Trauma to Recovery; Danser, who directed F***; and Blackburn, a former Bates debater who wrote and executive-produced Where Things May Grow.

In addition to Brimelow ’16, Bates-connected members of the Women in Media panel include Bumble Ward P’17, an industry publicist whose clients include director Sofia Coppola, and Amy Geller ’96, who co-directed, with Allie Humenuk, The Guys Next Door (2016), a documentary about a truly inspiring Maine family.

In this era of #MeToo, it’s timely “to have a panel on women in media, given the current climate in Hollywood, specifically. It’s really socially-politically pertinent and I think it will really resonate on campus,” says Gillian Coyne ’19, a double major in rhetoric and French from New York City.

The Bates Film Festival shows Father and the Bear, about an actor dealing with dementia, on March 24.

The social justice emphasis “happened organically,” Coyne notes. “It came about from us watching anything and everything, from Sundance selects to Bates grads’ work. It was something that the class winnowed out of all the films we watched.

“It was like playing a semester-long Tetris game, deciding what fits in and what gets priority. It turned into really fun, sometimes heated, discussions — filling up all the whiteboards, and who’s voting for what, and how do you prioritize the message that you want to get across.”

“Festivals have this image of famous people getting together to watch movies,” says Cavallero. “But the students have not seen this just as an opportunity to bring films to campus, but an opportunity to lead conversations on campus about important issues that this community and others around it are facing.

“So the festival is right at home in a rhetoric department, because it is very much about engaging the public discussion and being informed citizens. I’m really proud of the way that they’ve done this.”

Looking back to rhetoric professor Bob Branham’s 1992 shoe-industry documentary Roughing the Uppers and even earlier, Bates has had a close relationship with the moving image. And as Bates has redefined the liberal arts education as something that readies students for a life of meaningful work, it’s hard to think of a better academic course for that job than organizing a film festival.

For one thing, it’s assertively cross-disciplinary. “One of the things that I’ve been most impressed by, since I came here, is the number of people who teach film and the number of departments that those people are in,” says Cavallero.

“It’s a way of bringing in different perspectives and really having interdisciplinary conversations. Our hope for this year’s festival is that that happens.”

In addition, while the film-festival course provides ample grounding in theory, there was plenty of hands-on work to do too. “The skills that we’ve developed are really versatile and can translate into the workforce,” says Marisa Sittheeamorn ’18 of Bangkok — everything from catering arrangements to negotiating distributor fees. “It’s all been really interesting and new.”