The Bates College Museum of Art’s purchase of a painting by Marsden Hartley, a major figure in American Modernism, is one of the outcomes of a $100,000 grant to the museum from a foundation in New York City.

Half of the grant from the Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz Foundation for the Arts has helped fund the purchase of “Intellectual Niece,” a late Hartley work depicting his niece Norma Berger.

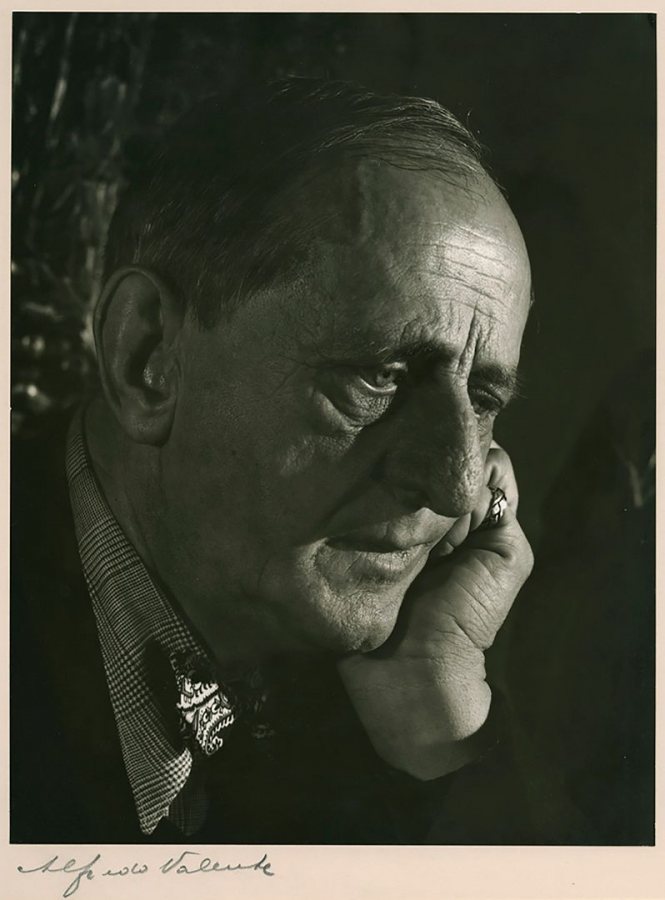

Marsden Hartley depicted in a gelatin silver print made around 1940 by Alfredo Valente, a photographer best-known for his images of Broadway actors and actresses. (Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection, Bates College Museum of Art)

The purchase dovetails nicely with the museum’s plan for the remainder of the grant, which was approved in February. The $50,000 will fund scholarly documentation of items in the museum’s Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection as part of the development of a fully accessible online catalog of the collection — a collection made possible by Berger’s generosity.

The museum’s Hartley collection comprises artwork by Lewiston native Hartley and other notable artists, his personal library, and a treasure trove of his personal effects.

“The Horowitz Foundation grant further strengthens a definitive Museum of Art resource,” says museum Director Dan Mills. “The Hartley Collection, which includes the largest collection of Hartley drawings anywhere, provides unique ways of understanding the life and creative work of an important American artist.

“The Horowitz grant, along with other recent grants, is enabling us to conserve, research, and document the collection, and to make it more accessible. And ‘Intellectual Niece’ is a significant painting that is important to and a great fit for the collection,” Mills continues.

“It’s gratifying that a leading arts advocate like the Horowitz Foundation shares Bates’ commitment to growing and stewarding this nationally valuable collection.”

“Intellectual Niece” was acquired from Nova Scotia residents Chris Huntington and Charlotte McGill. Art collectors and longtime supporters of the museum, “they have donated significant drawings of Hartley’s, as well as work by other Maine artists,” says museum curator William Low, who works closely with the Hartley Collection.

(The day after Low spoke to us for this article, he headed to Patten, Maine, to meet the couple and pick up their latest gift, an important donation of more than 75 works by Maine painter and Hartley contemporary Carl Sprinchorn.)

“Being able to acquire ‘Intellectual Niece,’ is a huge step for the museum,” says Low, “but it’s also part of a long-term relationship.”

“Intellectual Niece,” a 1939 oil painting by Marsden Hartley. (Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection, Bates College Museum of Art)

“Intellectual Niece” is the first significant Hartley painting, as opposed to works in other media, that Bates has acquired. Norma Berger was Hartley’s “most intimate relative later in life,” Low says. “She was his favorite correspondent, someone he was very close to.

“He frequently sent her gifts from his extensive travels, beginning when she was quite young. She was devoted to him, and the Hartley Collection is here at Bates because of her efforts.”

The collection grew from two gifts that followed Hartley’s death in 1943. His heirs gave Bates the remaining effects from his home and studio in Corea, Maine, in 1951. In 1955, Berger made a gift of Hartley artwork including 99 drawings.

In the 1950s, says Low, “Hartley was relatively unknown in his hometown. But he had expressed a hope that at some point he’d be recognized as a contributor to American art and his hometown. And Bates was fortunate to receive those gifts.”

The Berger portrait “brings together some loose ends in the collection. It depicts the person who’s responsible for the collection coming here. It connects with other works in the collection in special ways. We’re really grateful to the Horowitz Foundation for recognizing the importance of those connections.”

“Intellectual Niece” represents a transitional time in Hartley’s art. “He didn’t start painting figurative work until late in his career,” says Low. “This is a painting from a significant 1939 exhibition that was his first real exhibition devoted to figurative work.”

“We’ve been hoping to acquire this painting for years — this has been my single most important wish-list item literally for 20 years.”

Hartley’s influence remains potent. Just in the past couple of decades, his work has been the focus of high-profile exhibitions in Hartford, Fort Worth, Berlin, Los Angeles, and elsewhere, a string culminating last year with Marsden Hartley’s Maine, a landmark show organized and shown by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Colby College Museum of Art.

And continuing interest in Hartley means continuing interest in the Hartley Collection at Bates. Hartley scholars and aficionados visit campus increasingly often to avail themselves of the resource, says Low. The Hartley aura also attracts artists interested in the possibility of having their work included in the museum’s overall collection, whose roots in the Hartley holdings are evident in Bates’ collecting focus on drawings and works on paper.

Totaling more than 400 pieces, the collection includes art by Hartley in other media and work from his personal collection by friends and colleagues including Sprinchorn, Mark Tobey, and George Platt Lynes; Coptic, Mexican, and Asian textiles; pre-Columbian objects and Luristan bronzes; photographs; and the artist’s personal library.

“We’ve been hoping to acquire this painting for years — this has been my single most important wish-list item literally for 20 years.”

In sum, the collection affords unparalleled insights into Hartley’s work, his life, and his times. But fully realizing that value depends on work that will be supported by the Horowitz grant and by grants previously received by the museum from the Henry Luce Foundation and from the Coby Foundation.

The Horowitz grant focuses on updating scholarship for the various components of the collection, Low explains. The Luce Foundation grant is supporting more “mechanical” aspects of managing and cataloging the collection, such as making digital images of collection items and creating the online database. The Coby grant is funding conservation of the fragile textiles in the collection.

“The ultimate goal is an American art resource that will provide easier and more thorough access to the collection online,” Low says. But, he adds, “it is also intended to serve as an means of collection preservation.”

That is, as interest in Hartley grows, “the scholarship and online resource will contribute to the long-term care and preservation of the collection by reducing physical handling of fragile artworks and objects.”