NPR reports on ‘first-of-its-kind’ national study challenging the value of standardized tests

What was deemed a “bold step” by the Bates faculty in 1984 — their vote to make standardized tests optional for admission — has become a national march 30 years later.

NPR’s Morning Edition reports on a new study of 33 U.S. colleges and universities that yields more evidence to support what Bates instinctively knew back in 1984: that standardized tests do not accurately predict college success.

And at their worst, NPR reports, standardized tests can narrow the door of college opportunity when America needs to give students more access to higher education, not less.

Dean of Admission Leigh Weisenburger: Your high school transcript “is a much bigger story” than standardized test scores:

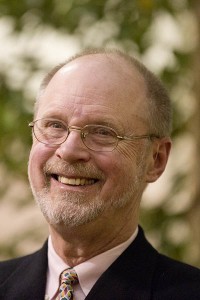

The study’s principal investigator is Bill Hiss ’66, former Bates dean of admission and now retired from the college. Valerie Wilson Franks ’98 is the study’s co-author and lead investigator.

Hiss tells NPR’s Eric Westervelt that “this study will be a first step in examining what happens when you admit tens of thousands of students without looking at their SAT scores.”

What happens, Hiss says, is that if students “have good high school grades, they are almost certainly going to be fine” in college, “despite modest or low testing.”

In terms of college access nationally, the authors pose a rhetorical question, asking whether “standardized testing produces valuable predictive results, or does it artificially truncate the pools of applicants who would succeed if they could be encouraged to apply?”

The answer “is far more the latter.”

Specifically, requiring standardized tests for college admission can narrow the door of college opportunity for otherwise capable students who choose submit test scores: “low-income and minority students, as well as more young people who will be the first generation in their family to attend,” reports Westervelt.

The recent study, “Defining Promise: Optional Standardized Testing Policies in American College and University Admissions,” looked at 123,000 student and alumni records at 33 private and public colleges. Submitter GPAs were .05 of a GPA point higher than non-submitters’, and submitter graduation rates were 0.6 percent higher than non-submitters’.

“By any standard, these are trivial differences,” write Hiss and Franks.

Roughly 3,000 four-year U.S. colleges and universities make SAT or ACT submissions optional.

Bates has studied its policy on a regular basis since 1984, so the new study is welcomed but not surprising to Leigh Weisenburger, dean of admission and financial aid.

“Prior to this 30-year study, Bates had done its own research, tracking the performance of submitters and non-submitters,” she explains. “Students who submit scores at the point of application and those who do not perform almost precisely the same at Bates.”

“We know that the best predictor of college success is the high school transcript,” she says.

Reciting a sentence that she says is practically a “Bates bumper sticker,” Weisenberg says that “while standardized tests are useful, we have found that three and a half years on a transcript will tell us much more about a student’s potential than three and a half hours on a Saturday morning.”

Annually, approximately 40 percent of Bates applicants do not submit any standardized test scores.

Standardized tests were sometimes “unhelpful, misleading and unpredictive for students in whom Bates has always been interested.”

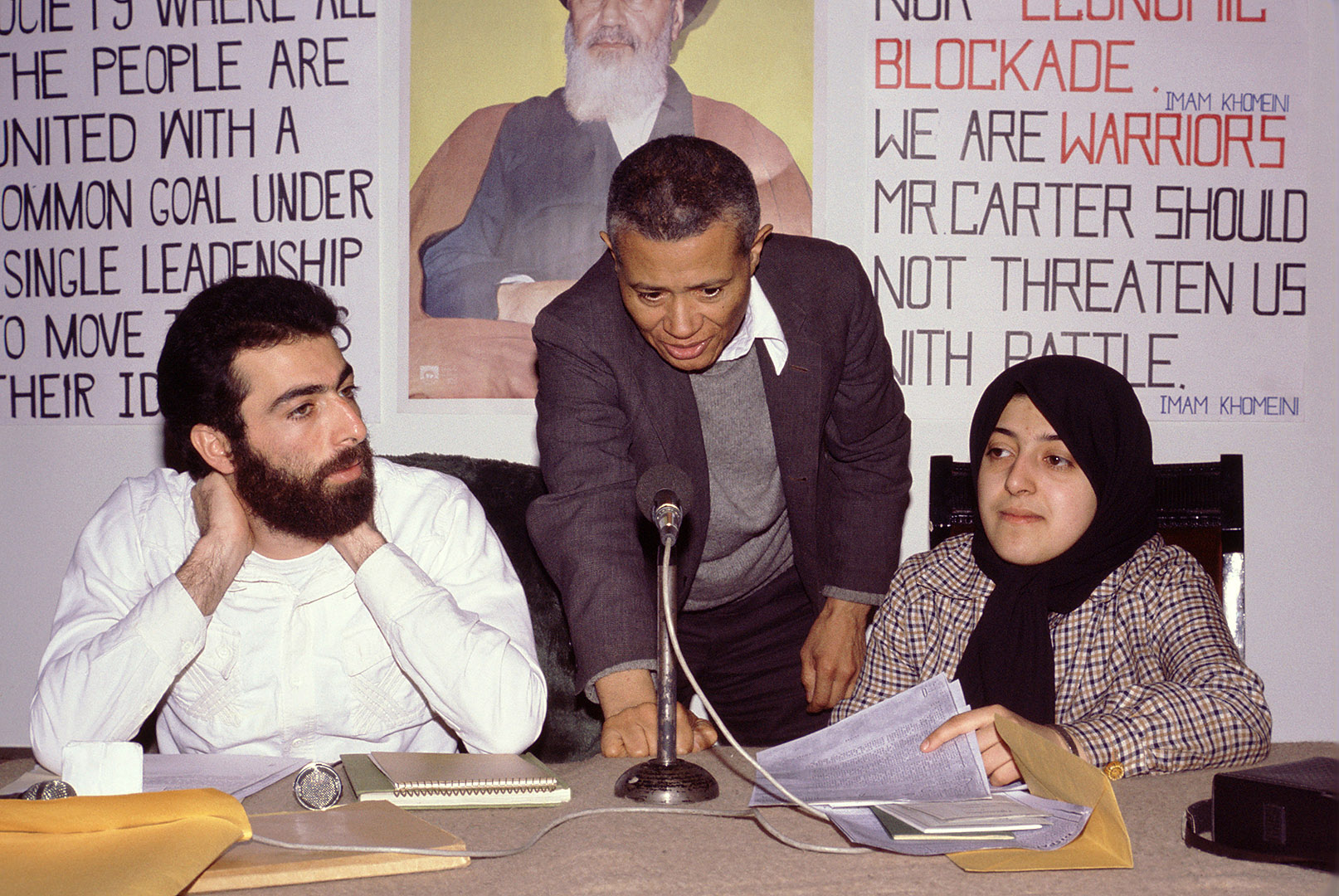

When the Bates faculty voted to make test scores optional on Oct. 1, 1984 — with Hiss as admission dean — then-President Hedley Reynolds said that action was “a bold step by the faculty, reflecting deep concerns with the effectiveness of the SATs.” (Bates became test optional in 1984 by no longer requiring SAT I. In 1990 all standardized testing became optional.)

A 1990 Bates Magazine story reviewing why Bates made the change noted that standardized testing by the 1980s was producing a kind of “mass hysteria” among high school students and their parents, “an unholy amalgam of passive surrender and frantic coaching for the test.”

It was also “a growing sense” that SATs were sometimes “unhelpful, misleading and unpredictive for students in whom Bates has always been interested,” including students of color, rural and Maine students, and first-generation-to-college students.

In 1984, the Faculty Committee on Admission and Financial Aid offered three reasons for recommending the policy change

1. SATs were an inaccurate indicator of potential.

2. Prospective applicants were using median test scores published in guidebooks as a major factor in deciding whether or not to apply to Bates. “The faculty realized that Bates should be seen first-hand,” said a story in the January 1985 issue of Bates Magazine. “Numbers cannot describe the tenor of a campus which has never had fraternities or sororities, a campus where students are respected as individuals.”

3. The relationship of family income to SAT success “worried the committee and conflicted with the mission of the college.” Noting the rise in SAT prep courses, the college worried that if coaching was successful, “it means that students with economic resources will enjoy undeserved advantages in admissions evaluations.”

In fact, the story said that Bates had studied the relationship of SATs to academic success for the prior five years, concluding that “the quality of the high school preparation (rigor of courses included) was consistently the best measure of the student’s potential at Bates.”