Open Forum: Winter 2011

Letters from the Winter 2011 Magazine

Please Write!

We love letters. Letters may be edited for length (300 words or fewer preferred), style, grammar, clarity, and relevance to College issues and issues discussed in Bates Magazine. E-mail your letter to magazine@bates.edu or postal-mail it to Bates Magazine, Office of Communications and Media Relations, 141 Nichols St., Lewiston ME 04240.

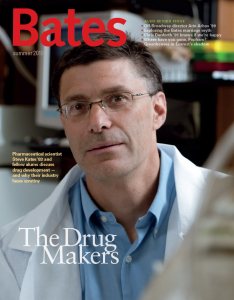

Drug Response

I read “A Drug Story” (Summer 2010) hoping for some precise insights into this high-risk and high-return industry, whose central challenge is, as Steve Kates ’83 puts it, that “many people don’t realize how many failures there are in this process and the costs involved in bringing a drug to market.”

It is critical to understand the number of failed attempts versus winning ones that drug companies are used to and thus what sort of justification they can offer in support of their pricing and other business practices. To say that “without profit you wouldn’t have the incentives or resources to innovate” only nibbles around the edge of the issue. Exactly what amount of investment versus payoff is typical for drug companies? Wouldn’t knowing this help readers understand why drug companies should be allowed to (1) pay physicians to prescribe their drugs and (2) “pay to delay” the introduction of cheaper alternatives to market? And shouldn’t this discussion recognize that these companies compete in and affect a worldwide market including, for example, Africa, where human need is nearly immeasurable?

David Farnsworth P’11, P’13, South Royalton, Vt.

Steve Kates speaks to the risk-return question:

“The return on pharmaceutical R&D isn’t as productive as in other industries and the profits are often lower. In 2006, a Congressional Budget Office study, Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry, noted that pharmaceutical firms invest as much as five times more in research and development, relative to their sales, than the average U.S. manufacturing firm. The study also noted that increasing sales revenue has been matched by increases in drug R&D spending. “In addition, it’s not the return from the investment that’s key, but the return to continue to invest, and drug discovery is more and more difficult because addressing the indications (diseases) and targets (biological pathways) is so complex. The increased investment and shorter patent lifetimes mean that companies do what they can to recoup investment and future costs. While profit-based and research-driven innovation is aesthetically unappealing, it is the only system that’s proven effective.”

Adding another voice to this discussion, Associate Professor of Chemistry Jennifer Koviach- Côté posed Farnsworth’s final question, about the global context of drug development, to students in her first-year seminar, “A Drug’s Life.” The students wrote:

“Human need is certainly immeasurable in both developed and developing countries. However, there is a limit to what pharmaceutical companies can do based on the economics involved in the discovery and production of new drugs. We must recognize that providing drugs to developing countries will result in higher prices locally and less availability to Americans. In addition, the current means of delivering drugs to the needy are not effective due to corruption and lack of personnel and infrastructure. In the future, the creation of re-engineered products to suit developing countries’ economies may offer a solution to the current problems.”

‘Corporate Blandishment’

Since the whole pharmaceutical industry is exploitative and loads its pills with such high costs, why give them free advertisement? Admittedly, Steve Kates ’83 is Bates, and thus bears mentioning, or at least he needs to be recognized. But frankly, I’m not impressed with people who say that without the drug profits there would not be the incentive to innovate. That’s apparently how their revenues grow, as you say, at about 8.6 percent per year.

Why not do something which is not corporate blandishment, such as Bates and education or Bates and the military, both of which would involve a number of less self-seeking graduates?

Arthur Knoll ’51, Sewanee, Tenn.

Incentive to Invest

As a patent attorney representing Steve Kates’ firm, Ischemix, I should clarify the article’s explanation of the 20-year patent term for new drugs. The clock does not start running when a drug is patented, but actually several years earlier when a patent application is first filed.

The first patent application for Ischemix’s CMX-2043 was filed in 2000, and the drug is not projected to be approved by the FDA for several years. Similarly, the first patent application for Ecallantide, which Mike Bonney ’80 of Cubist discussed abandoning in the article, was filed in 1994, and the drug was not approved by the FDA for any indication until 2009. (Ecallantide was developed by another client, Dyax.)

In both cases, these companies invested millions of dollars and the passion of their employees to develop a drug to meet the unmet needs of a population of patients, only to be faced with perhaps five years of patent exclusivity, out of the hypothetical 20, to recoup their investment.

Fortunately, there are ways for these companies to extend their patent and non-patent market exclusivity, but Bonney is right: The pharma business model leaves many potential investors scratching their heads.

Jaleen Milligan ’90 and I (yes, we’re another statistic) will continue to happily pay large amounts of money on drugs to manage our younger daughter’s Type 1 diabetes because we know that those life-saving drugs would not have been developed without that incentive for companies to invest in their development. And the cure for Type 1 diabetes will not be developed without that incentive either.

Michael Siekman ’90, Lexington, Mass.

Making the Most of Marriage

I appreciated Maura McGee’s article and Marty Braun’s illustration (“The 60 Percent Solution,” Summer 2010). The illustration shows, I believe, that marriage, Batesie or otherwise, is not just a white heterosexual privilege, which I interpret as a subtle statement in favor of marriage equality. Thanks!

Emily Blowen Brown ’65, Ely, Minn.

Cover Question

Several things came to mind as I read the Spring 2010 issue and the articles revolving around Islam. On the cover, Joanie Meharry ’07 is wearing a hijab while in Afghanistan. Was this a way to fit in, or a requirement under Shariah law? There’s a world of difference. As a Bates religion major, I and others were encouraged to challenge our beliefs, and rightfully so.

As a Marine reservist, I left Bates during Operation Desert Storm to serve in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. When I got back, many students assumed I did not want to go overseas, figuring that I joined the military for the GI Bill. They were surprised when I told them I learned more about life and the world during my six-month deployment than I ever did in a college classroom. For example, in Saudi Arabia, we were told only Islam could be practiced. Unaffiliated with any religious tradition, it did not bother me as much as it did the many Christians in our unit, who were told they were not allowed to pray.

Then, I read the article “Folks Back Home,” about the friendship between two students, one an Afghan and the other a Marine combat veteran. I am glad to see veterans going to a school such as Bates, and have to say that I was treated with respect by all my fellow students, as well as staff and professors, when I returned to the classroom.

Will Selling ’93, Oxnard, Calif.

Joanie Meharry explains why she wears a hijab:

“As a foreign woman living in Kabul, the choice to wear a headscarf is my own. It is considered good etiquette and a demonstration of respect for the culture where I am a guest. While walking the streets of the city I feel safer and at public events I feel more comfortable. Indeed, I am often more concerned about the position of my scarf than my Afghan friends. Aesthetically, a headscarf frames the face even more elegantly than when a Western woman dons a hat; and the raw silk scarves from Mazar-i Sharif or the range of soft cotton and silk scarves imported from India are coveted items. Practically speaking, it better protects the hair and neck from the dust and wind, whether in Kabul or Connecticut. Thus, I appreciate my right to choose, but I would never choose to do otherwise.”

Location, Location, Location

A correction to the story “They Love the Sixties” (Summer 2010). The SNCC 50th gathering was indeed at Shaw University, but that school is in Raleigh, not, as the story said, in Charlotte.

Frances Curry Kerr ’50, Matthews, N.C.

Body Art

Thank you for your story “Sharp Pencils and Sweat” (Summer 2010) celebrating Joseph Nicoletti’s Bates career and artistic accomplishments. I was not an art student at Bates and never took one of Professor Nicoletti’s classes. I was, however, in many of those classes as a model.

Being a model for figure drawing classes is still the most physically strenuous job I have had. Taking my clothes off in front of a room full of my peers was a daunting experience but also one of the most empowering of my life. Joe taught his students to look at me like art — they noticed the shape between arm and torso, knee and shin, chin and neck.

I would often stay through the full class to listen to students’ critiques of each other’s pieces — it was intellectually challenging work. I heard the intensely personal feedback he provided to each artist as he circled the room during those classes. I noticed the care with which he offered praise, and constructive feedback. For me personally, though, Joe gave me an incredible gift: The ability to think of my own body as a work of art.

Kirstin McCarthy ’03, Washington, D.C.