Webster Harrison ’63, a revered football and lacrosse coach from the 1970s into the 1990s who inspired his students with a fusion of Bates ideals and practical values gained as a Marine Corps combat veteran, died June 17 at age 78 after suffering cardiac arrest at his home in Auburn, Maine.

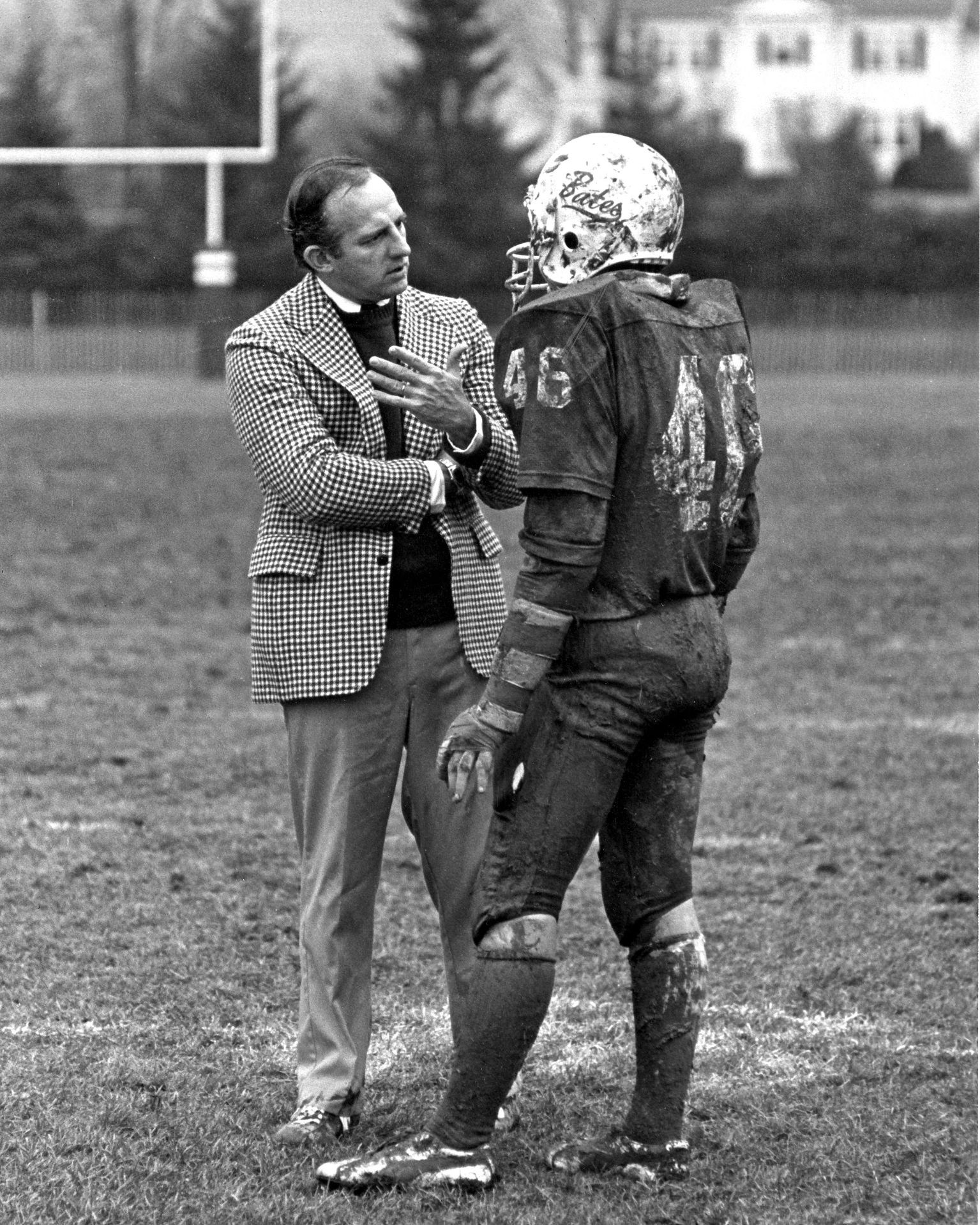

Appointed in 1974 as an assistant coach of football and track, Harrison would serve as a head coach in three Bates sports for a total of 35 seasons.

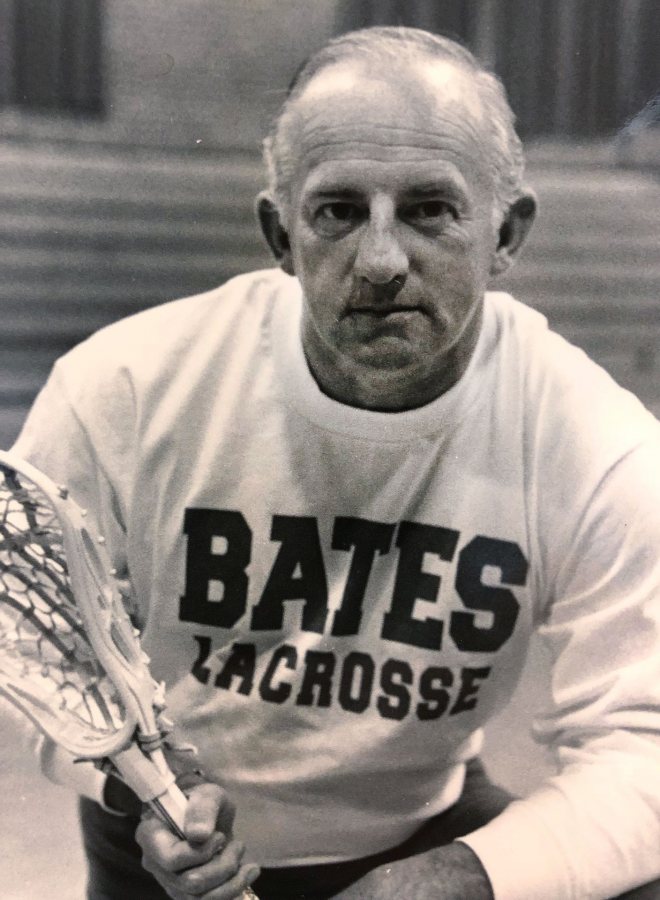

He led the football program from 1978 to 1991, winning four CBB titles. As the founding head coach of the men’s varsity lacrosse program, he led the team from 1977 to 1995, earning ECAC tournament berths in 1984 — and receiving New England Lacrosse Coach of the Year honors that year — and again in 1987.

Memorial Gift and Service Information

Memorial gifts may be made in Web Harrison’s memory to Friends of Bates College Athletics, Office of College Advancement, Bates College, 2 Andrews Road, Lewiston ME 04240. A memorial service will be held at the Gomes Chapel at a later date.

A longtime associate professor of physical education, Harrison also served as head coach of women’s track and field for two years, 1977–78 and 1978–79.

After coaching, Web joined the Office of College Advancement, where he established the Bates Parents & Family Association and gave programmatic focus to the emerging culture of parent philanthropy. He retired in 1999.

For his players, Harrison provided a way to live life with value and purpose. “He had uncompromising integrity,” said Peter Wyman ’86, who played football for Harrison and is now senior vice president for cooperative development

“For many of us, his example has been a beacon and guidepost all our adult lives. He transcended the role of coach. He challenged us to make the right and best decision, to do it right the first time, and to develop standards and values and hold tight to them, especially in difficult times.”

Web Harrison ’63 talks with one of his Bates football players on Garcelon Field, circa 1982. (Courtesy Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library0

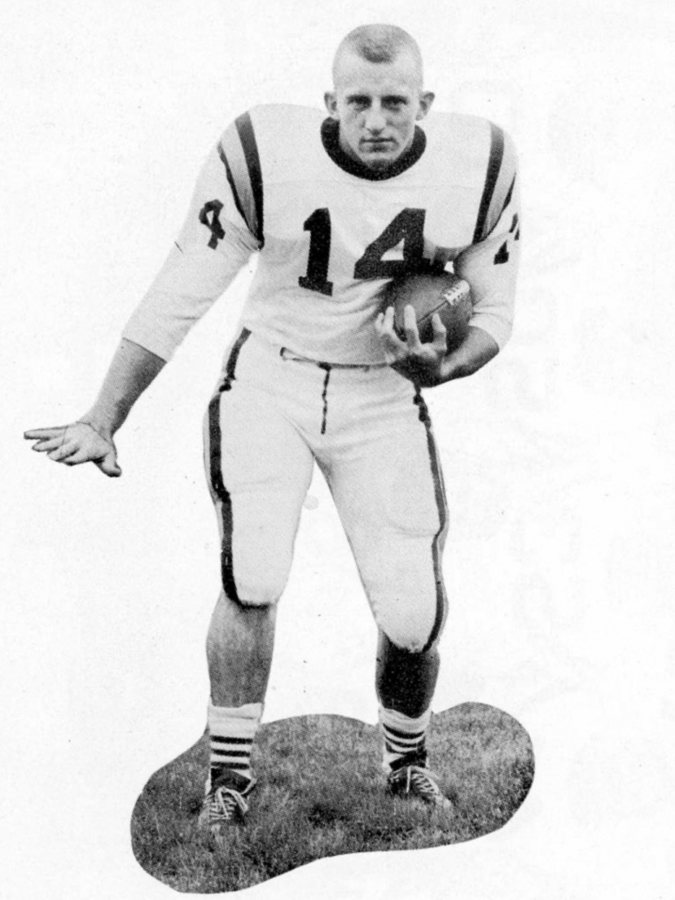

Harrison was a native of Torrington, Conn., whose maternal grandfather, William E. Webster, was mayor of Lewiston in the early 1900s. A biology major at Bates, he was a four-year member of the football team, a sportswriter for The Bates Student, and part of the Mirror business staff.

As a Bates Student sportswriter noted, Harrison was “small for a fullback — 5-10, 170 pounds — but a vicious blocker.”

He decided to join the Marine Corps during his junior year and completed the required Platoon Leaders Class the summer before senior year. His Bates roommate Thom Freeman ’63 recalls the shock of returning to their dorm that fall. “Our room was never the same. The doorknob was Brasso’d and shoes had to be spit-shined.”

“Most everything he did revealed his deep love of Bates.”

Harrison lived Bates and Marine Corps ideals and values, said one former player, Steve Brackett ’85.

“He had an innate sense of responsibility for the people around him. And he was exacting. When you crossed that line onto the field, your socks were pulled up and your helmet strapped because if you’re going to do something, you do it right.”

Brackett, now partner and head of strategic partnerships and business development for Shepherd Kaplan Krochuk in Boston, says that Harrison “also had tremendous respect for the history and egalitarian legacy of Bates. He knew more about Bates than anyone I knew. He lived Bates. He embodied it.”

“We all knew he was a Marine and had served in Vietnam, but it was also always clear that he was a Bobcat,” recalls David Hild ’84, who played lacrosse and football for Harrison for eight sports seasons and is now a dean at Kingswood Oxford School in West Hartford, Conn. “And most everything he did revealed his deep love of Bates.”

“He loved competition and loved to win, but not at any cost — a great lesson that he passed along to his players to keep us grounded in our own careers.”

Above all, he “was always concerned that his players represent Bates. He wasn’t interested in just ‘football’ or ‘lacrosse’ guys. They had to be more than that in the Bates community.”

“He loved competition and loved to win, but not at any cost. He had his core values that kept him grounded — a great lesson that he passed along to his players to keep us grounded in our own careers,” said Andy McGillicudd ’85, a football and lacrosse player who is now CEO of Endocellutions.

Web Harrison ’63 (second from left) prepares to tee off with lifelong friends, from left, Chick Leahey ’52, Howard Vandersea ’63, and Bob Flynn at a Reunion golf outing in 2005. (Jay Burns/Bates College)

The character of Harrison’s players was the focus of a 1982 profile by a Maine Sunday Telegram columnist. Harrison produces “gentlemen-athletes,” wrote Hank Burns. That might sound corny, he told readers, until you hear from Roger Park, then the college’s athletic trainer.

Harrison “always was able to cut through the crap to say, ‘Here’s why you should appreciate someone.’”

“Web attracts good citizens,” Park said. “I’ll be honest. When I first came here, before Web, the kids we had on the team treated me as some sort of machine designed just to service their needs. The kids we get now…are genuinely interested in me as a person and in the work I do.”

Steve Brackett explains how Harrison taught his players to appreciate the humanity of the people around them. One fall day, Harrison called Brackett and two football teammates, Rico Corsetti ’85, and Rich Sterling ’85, over to his office. “He said, ‘Roger just got a couple cords of wood delivered. Could you help him stack the wood? You’ll get a spaghetti dinner from his wife.’”

Thus began a four-year tradition. “After the first year, we asked if we could stack it again for him. That’s how we got to know Roger and his wife.”

Harrison “always was able to cut through the crap to say, ‘Here’s why you should appreciate someone,’” said Bracket. “He would always say, ‘Help other people up the ladder.’”

When people talk about Web, phrases like “it’s a cliché but…” come up a lot. Clichés exist because they’re true. “Web created a family among his players,” Brackett says. “It’s a cliché, it’s overused, but we felt that way. Every day I get to look at a photo in my home of my wedding, and there’s Web, beaming with a cigar and a drink, surrounded by his players.”

Brackett recalls having film sessions with a 16mm projector in Web’s family room. In those sessions, Harrison’s focus was never on mistakes but on making decisions. “He allowed you to make mistakes. He didn’t hammer you.”

Brackett recalls Harrison pressing the clicker to make the film go backward and forward. “Back and forth, back and forth, always with one question, ‘What could you have done differently?’”

Those sessions helped Brackett think like a leader.

“By the time you were a senior, Web wasn’t yelling instructions from the sideline. He expected you to adapt, or call an audible and make it work. He allowed you to make your own game plan. That’s what life is about: figuring out how to look at something three ways rather than one, to find options, to bring people into the success.”

Other times, cliches can obscure finer details. Harrison was a Marine, but “he could laugh at himself,” recalls Hild. “He famously joked about his lack of lacrosse knowledge prior to being named head coach. But like everything he did, he put his heart and soul into it and became a fine and respected leader of that program.”

“He wanted you to come off the field physically spent but full of pride.”

He could be introspective, too. With the football team struggling to a 1-6-1 record in 1983, “Web was candid, openly assessing and asking for input about how he might improve himself. He was an honest and friendly man.”

With Harrison, Brackett continues, “you didn’t always have to succeed. He never faulted you for losing. But he would fault you for not giving 100 percent because you were not doing yourself any favors.

“You just had to look in his eyes when you came off the field to know if you weren’t giving it all. He wanted you to come off the field physically spent but full of pride.”

Fatherless from a young age, Brackett always saw Harrison as a father figure; he was a rock that he and other former players could lean on. “Any time I called Web, just to check in, he would always respond, “Stevie, how can I help you?”

As a player, “there was a clear line between us and him as a coach,” said Bracket. “But it was always about respect first. When we graduated, he continued to take a great interest in our lives and pride in our successes,” said Brackett.

“Web would get a gleam in his eye when he was talking about one of his guys doing something that made him proud,” recalls Hild. “And ultimately, most of us truly cared about making him proud.”

Web Harrison poses with his former players, including Steve Brackett ’85 (center, bow tie), at Brackett’s wedding reception. “As a player, there was a clear line between player and coach,” said Bracket. “But it was always about respect first. When we graduated, he continued to take a great interest in our lives and pride in our successes.” (Photo courtesy Steve Brackett)

Harrison cultivated diverse interests. Before joining the athletics staff in 1974, he and his first wife, Virginia Erskine Harrison ’63, took a stab as organic farmers in Fayette, Maine. “But I could never coach the rocks from the lands,” Harrison would say.

In 1988, the Lewiston Journal featured him in a story about local coaches who prepare distinctive dishes for Super Bowl parties. Cooking, he said, “is almost like coaching. “You put a plan together and see results — faster than you do in coaching.”

Harrison’s recipe for “Buffalo Wings Plus” was featured, and he touted one of his drink recipes. “Beat Bowdoin Greasewood Golden Margaritas,” named in honor of a big Bates football victory.

Then there is Harrison’s huge spread of daffodils — some 12,000-plus in 14 gardens — that would bloom each spring in front of his home in Auburn and that he would deliver to area schools and medical nonprofits, including the Dempsey Center and Androscoggin Home Healthcare and Hospice.

“Marines, athletes, daffodils,” he said — “you start them all young and nurture them.”

In May 2017, Web Harrison ’63 sits amid some of his daffodils at his Auburn home. Each year, he donated the blossoms to area nonprofits. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

An unusual legacy at Bates is that Harrison coined the famous Bates cheer, “It’s a great day to be a Bobcat,” an amalgam of Bates and Marine Corps cultures.

As officer candidates, he and his fellow Marines were expected to greet officers this way: “Good afternoon, sir, and welcome to another grand and glorious day to be alive and a member of the U.S. Marine Corps, where every day is a holiday and every meal is a banquet.”

Web brought the sentiment to Bates, where the saying got shortened to, finally, “What a great day to be a Bobcat.” “I’m actually very happy that it’s being carried on,” Harrison said in 2013.

During Reunion 2013, Web Harrison explains how he coined the Bates rallying cry “It’s a Great Day to Be a Bobcat.”

The story about Harrison joining speaks volumes about the U.S., pre-Vietnam. His classmate Alan Marden, fearing that he was going to flunk Shakespeare and thus flunk out of Bates, wanted to check out military service. For support, Harrison accompanied Marden to the Marine Corps recruiting station.

“As it turned out, Al did all right in Shakespeare and didn’t join the Marine Corps,” recalled Harrison in a 1998 Bates Oral History Project interview. “But I did.”

In his Bates oral history interviews, Harrison often had to detangle his decision to join the Marines from a common perception of the era. While it was the 1960s, it was not yet The Sixties. Vietnam wasn’t on everyone’s radar, and World War II was less than 20 years in society’s rearview mirror.

“Young men who grew up at the time I did,” Harrison said, “heard an awful lot about World War II from older relatives, and all you heard were the good things. I had something that I owed to my country. And it was also a challenge. I felt that being an officer in the Marine Corps would help me figure out what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.”

“I get what America means,” he added. “I get the benefits of what America means. So, how do I help preserve what that means? Service is one way.”

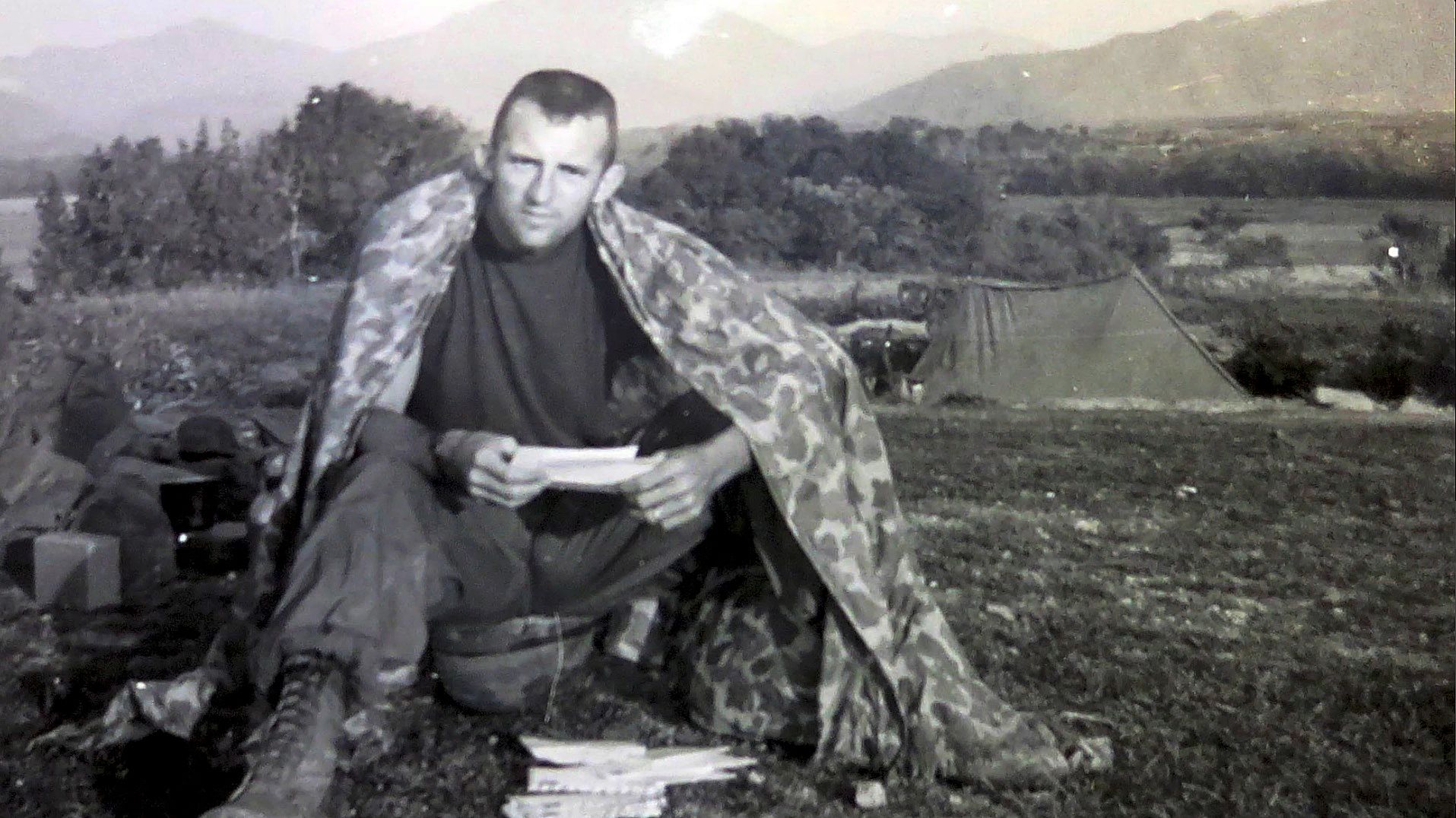

He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Marines on the day he graduated in 1963. Two years later, in 1965, he was among the first U.S. combat soldiers deployed to Vietnam.

His experiences as a Marine Corps infantry platoon commander, company executive officer, and battalion and regimental operations officer in and around Da Nang Air Base are referenced in the acclaimed Vietnam memoir A Rumor of War by Philip Caputo.

The book is a graphic and unvarnished account of the long war’s earliest months. In one scene, Harrison looks out over the Marines’ encampment, which Caputo describes as “everything aboveground, uncamouflaged, laid out in tidy rows, and nothing between it and the VC but a roll of rusting concertina wire.” Looking at the vulnerable scene, Harrison speaks of the past and future when he says, “Jesus, Phil, even the French dug in.”

The book has “got its mark on me, and probably a lot deeper than I would like to admit,” Harrison said in 1998. “I don’t know whether it’s bad or good or what, but it certainly has had a very big effect on me.”

Harrison classmate Howard Vandersea ’63, part of a tight-knit group of Bates friends from the early 1960s, was head football coach at Springfield and later at Bowdoin, from 1984 to 1999. He faced Harrison-led teams eight times.

Military service in Vietnam, says Vandersea, “formed the person Web became: disciplined, goal-oriented, a leader, a patriot.” In 2013, Harrison and several classmates gave a Reunion talk about their Vietnam experiences. “He was consumed with the study of Vietnam,” Vandersea says, “its history, its people, and the ‘why’ of the war.”

Web was discharged from the Marines as a captain in 1967. He did graduate work at Boston University and served as an assistant football coach before moving to Maine in 1974.

“None of that had to do with their athletic ability. It had to do with helping them be the best person they could be.”

He turned to coaching, he said, because he regarded his own coaches, people like the late Bob Hatch and Chick Leahey ’52 (both Marines) “as people that I thought led exemplary lives. They were true role models for me, and I think in many ways that’s why I wanted to get into coaching — I thought, what a great way to spend your life.”

In his oral history, Harrison said that coaching was most rewarding when he helped students “who had the toughest time here. Those were the ones that I felt were my successes — students who changed the most in the course of their time here and who came in and needed help and needed direction.

“None of that had to do with their athletic ability. It had to do with helping them be the best person they could be. Those were the ones who I remember most fondly.”

As he told an interviewer in 1982, “I’m probably a pretty poor X’s and O’s coach. I probably spend too much time in the locker room with the players just talking and finding out what’s going on in their lives.”

His experience in the Marines, he said, “gave me a chance to see if I could fill a leadership role. And I liked it. I found out that I could do it reasonably well. As I view coaching now, I’m kind of doing that same thing: I’m having an influence on young men in not too different a way from what I did when I was in the service.”

Alumni like Brackett have felt it all their lives.

“I’ve coached youth leagues, and I can’t step on a field without thinking about him,” Brackett says. “I relate so much about my life to Web. I credit him with success in business, family, and friendships. Web taught me about living with integrity and a moral compass.”

Harrison’s survivors include his wife, Kathleen McEntee Harrison, a daughter, Kathryn Harrison, and her husband, Tim Smith; and a granddaughter, Delia Smith.