Never Too Late

In the summer of 1972, Rocky Wild Mossman ’67 and several other Navy wives fly to Hong Kong to meet their husbands’ aircraft carrier, the USS Kitty Hawk. Except for one bash with the officers and wives, Rocky and Harry Mossman ’65 spend their days and nights with just each other.

Rocky gives him cookies that she and their sons, Tom, 4, and Bill, 2, made together. At one point, Harry shows her — but doesn’t give her — a sheaf of handwritten pages, a letter to be delivered to the boys if Harry, an A-6A bombardier-navigator, is killed in action.

“I read it briefly,” Rocky recalls. “But I remember not wanting to deal with the possibility of death that they were dealing with every day.”

A month later, the possible has become real.

Harry and his pilot, Roger Lester, are reported missing after their fighter-bomber, call sign Viceroy 502, disappears the night of Aug. 20, 1972, over heavily defended Haiphong, North Vietnam. A radio transmission is heard: “Let’s get the hell out of here.” An explosive flash illuminates the clouds.

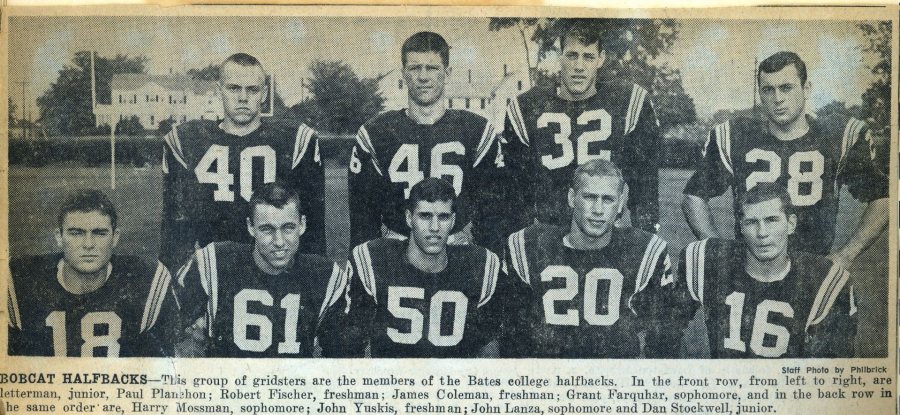

In 1972, members of the VA-52 Knightriders, including Harry Mossman ’65, seated third from left with glasses, prepare to depart Naval Air Station Cubi Point in the Philippines for combat operations off North Vietnam aboard the USS Kitty Hawk. Roger Lester, pilot of Mossman’s ill-fated A-6A fighter-bomber, is at the steering wheel. At far left, in aviator glasses, is Mike Smith, who would be pilot of the doomed space shuttle Challenger in 1986. (Photograph by Greg Wood)

Back in Oak Harbor, Wash., near Whidbey Island Naval Air Station where Harry’s VA-52 squadron is stationed, Rocky prepares to tell her two boys.

“In Oak Harbor it just wasn’t unusual for a father to be missing,” she recalls. “I was trying to be the stoic New Englander, so I just told these two little kids, ‘Our daddy won’t be coming home with the ship. He’s missing, like Jerry and Terry’s daddy.’”

She’s told that Harry is almost certainly dead. But a year later, when the POWs come home, the Navy puts Rocky and other wives of missing airmen on alert in case their names come up during debriefings. But no one speaks of Mossman or Lester.

“I feel bad that I was silent about their father,” she says. “But I strived not to be the pitiful widow.”

In 1975, Rocky remarries; so that the wedding can occur, the Navy makes a finding of death in Harry’s case. (Her second husband, Terry Moore, will later die in a car crash, and years later she marries a third time. That’s the last name she uses today — she is Rocky Harvey.)

The memory of Harry recedes. Rocky doesn’t try to keep it alive. “I feel bad that I was silent about their father,” she says. “But I strived not to be the pitiful widow, and I didn’t want to perpetuate a myth that [Bill and Tom] were poor children because they lost their father.”

Rocky later corresponds with other Vietnam widows and sees a pattern. “We didn’t talk about our husbands or Vietnam. You just didn’t know what kind of reaction you might get.”

Harry’s entire side of the family seems to fade away. His parents, Julian ’27 and Eleanor Seeber Mossman ’27, are dead by 1967. Harry’s only sibling, Carol, dies relatively young.

But there is Harry’s letter, 25 pages of lined tablet paper, filled on both sides. Reluctant to read it in Hong Kong, Rocky’s first thought after Harry’s plane goes down is: Get that letter. Harry’s roommate, Larry Yarham, sends it to her.

Their son Bill first reads the letter in his Central Washington University dorm room. “It was like going through 20 years of his hopes for me in one sitting,” he says. “Some things I agreed with. Some I didn’t. And some made me cry. I knew he was trying to do the very best he could as our father.”

Harry — the quiet, clear-thinking English major, the determined if undersized football player nicknamed “Harry the Horse” for how he kept on keeping on — would write to his sons: “Many persons have learned things from the dead individual…. In some small way, living persons share parts of his soul, conscious or otherwise.”

He expresses the conflict between military duty and his belief in rational thought. “The saddest part of the job I have undertaken is that the armed services represent… the last resort, when rational solutions… have failed.”

For Bill and Tom, growing from boys to men, the fact that his remains never come home is the yeast for unwelcome fantasies. “It was always in the back of my mind,” says Bill, now 34. “What if he somehow was alive? What if I’ve met him, but his memory is gone and he doesn’t know me?”

By the 1990s, the closure isn’t perfect, but Rocky doesn’t participate in the call for “full accounting” by MIA families. For one, she long assumed that Harry went down over water, making recovery of a body impossible. And there dewas a memorial service and other Navy ceremonies and dedications.

“I had no idea about the grim reports I would get.”

“I just braced myself to go on, and I felt like I’d done enough of those things,” she says. Trying to be a rock, however, takes its toll and she suffers bouts of depression. “Being stoic didn’t work.”

Then the letters begin to arrive.

In 1994, an A-6A crash site is found east of Haiphong. With each discovery at the site, elder brother Tom receives a terse military letter detailing the findings.

Looking back, Rocky is today awed by the military’s scrupulous efforts to find and identify remains of lost soldiers. (The Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command directs those efforts, and according to its Web site 78,000 Americans are missing from World War II; 8,100 from the Korean War; 1,800 from Vietnam; 120 from the Cold War; and one from the Gulf War.)

But at the time the letters are unsettling. “I had no idea about the grim reports I would get,” says Rocky. “Bits of flight suits. A report from a neighboring village about a boot. It felt macabre. The Navy was doing this in an entirely honorable way, doing what the military has always done. But for me, it felt 25 years too late.”

But, in a sense, it was just in time. As the letters arrive, Tom asks his mother about Harry, and she puts together an album: Harry’s Bates report cards and papers, drawings he’d made of their dream house, photos. She writes a note to Tom: “Thank you for asking to know more about him as a man.”

In 2003 a Joint Accounting Command team recovers bone fragments. Next comes DNA analysis, which in this case requires a blood sample from a relative besides Tom or Bill. Harry’s only sibling, Carol, is dead, but fate lends a hand: Carol’s daughter has reconnected with Rocky in the past year, after her son finds a Web page tribute to Harry as part of a genealogy project. “You start being a believer when something like that happens,” Rocky says.

“I didn’t think this would strike me as it did. Yet this has been very — very — good for us.”

In May 2004, using a blood sample from Harry’s niece, his remains are ID’d. (No identification has been made for Roger Lester.) In August, Harry’s burial takes place in Kent, Wash., and Bill delivers the eulogy: “There had always been a part of me that wondered — and even hoped — ‘What if they got out of that plane?’ That little part of me is now being put to rest with my Dad’s recovery.”

As for Rocky, a woman who always tried to look ahead, she is stunned by the impact on her life of this final chapter of her and Harry’s story together, one that began with a chance meeting in the Bobcat Den more than 40 years ago.

“I am more settled and peaceful than I ever thought I would be,” she says. “I didn’t think this would strike me as it did. Yet this has been very — very — good for us. We are a close family. But we are now closer.”

The A-6A Intruder

Displayed at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Wash., is a vintage A-6 Intruder painted in the scheme of the plane, call sign Viceroy 502, that flew from the USS Kitty Hawk and was shot down in August 1972, killing Harry Mossman ’65 and Roger Lester.

Their names appear on each side of the canopy.

.