Bates, Morehouse debate King’s ‘Dream’

As debaters from Bates and Morehouse colleges made clear on MLK Day, discussing Martin Luther King’s dream raises more questions than it answers.

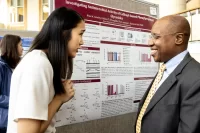

Debater Shannon Griffin ’16, left, listens to an objection Monday during the Reverend Benjamin Elijah Mays Debate between Bates and Morehouse colleges in the Olin Arts Center. (Sarah Crosby/Bates College)

“King didn’t want to change people, he wanted a better society,” said Morehouse sophomore Rami Blair, who went on to quote King’s own words: “The law cannot make a man love me, but it can keep him from lynching me.”

Representing the opposition, Blair and Morehouse junior Curtis O’Neal argued against the day’s motion: “This house believes King’s Dream is unattainable.”

Yet the core of the Jan. 20 debate was not so much whether King’s dream was unattainable, but what the dream was to begin with. The teams sparred over the definition of the dream and what King meant when he wished that his children “not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

The Morehouse debaters pointed out that King was, in Blair’s words, a “practical optimist,” not the radical idealist many perceive him to be. The dream was to create equality of opportunity under the law — not a color-blind utopia.

Bates’ Brooks Quimby Debate Council team supported the motion, arguing that the oppression within U.S. education, economic and criminal justice systems makes true equality impossible.

Represented by Stephanie Wesson ’14 of Mount Vernon, N.H., and Shannon Griffin ’16 of Philadelphia, the Bates team maintained that the dream was an idealized vision of a U.S. in which race no longer matters.

The annual tradition of the Reverend Benjamin Elijah Mays Debate honors the man who is at the center of the historic friendship between Bates and Morehouse.

Former captain of Bates’ debate team, Mays ’20 became the president of Atlanta’s historically black Morehouse College in 1940. He was a national figure in the civil rights movement as a theorist and as spiritual adviser and friend to King, who graduated from Morehouse in 1948.

Jan Hovden, Bates professor of rhetoric and director of debate, explained that the day’s motion was intentionally provocative in order to illustrate the power of “the spoken word above that of violent revolution.”

Professor Kenneth Newby, director of Morehouse’s forensics program, emphasized the importance of such cultural and intellectual exchange. “We consider Bates College a true friend of Morehouse College.”

The debate was in keeping with themes presented by that morning’s keynote speaker Gary Younge. An award-winning journalist and author, Younge argued that King was far more complex and polarizing than history tends to remember.