Leading up to the election, we asked Bates folks to share stories recalling their first U.S. presidential vote. Their stories that went beyond ballots and candidates to capture feelings of pride and responsibility — and a deep awareness of what it means to protect one’s vote.

Áslaug Ásgeirsdóttir

Professor of Politics and Associate Dean for the Natural Sciences and Mathematics

I grew up in a politically active household in Iceland, where voting was something you were expected to do. When I first began to vote in Iceland, I was always struck by how my grandparents’ generation dressed up for going to the polls. It was clearly a day of celebration. I soon realized that this was probably because they had experienced Iceland becoming an independent country in 1944, after centuries of Danish rule. They did not take voting for granted: It was something to celebrate.

Because I emigrated to the United States, I lost my ability to vote in Iceland’s elections, and I was not able to vote anywhere until decades later, when I became a U.S. citizen in 2015. My first time voting in person was on June 16, 2016, in primaries at Auburn Middle School. It was a big day for me.

The first presidential election vote however was a bit anticlimatic as I was on sabbatical, and thus away from Maine and submitted an absentee ballot, which I have done again this year. It is not quite the same.

James Reese

Associate Dean of Students for International Student Programs

I was eager to participate in my first vote since the large question was whether Atlantic City, N.J., would implement legalized gambling.

I lived in Cherry Hill, N.J., just outside of Philadelphia. I was suspicious, since the proposal stated that taxes from the gambling would serve as a new foundation to fund the public school system of Atlantic City, where the large majority of students were African American. While the gambling vote easily won, I observed then, and over the years since, little increased funding went to schools, making little difference.

The larger meaning behind my voting for the first time was to honor the legacy of African Americans, including my parents’ attempt to gain voting rights.

In 1959, my family was living in Alabama. My father was not able to vote due to not being able to register. While all U.S. citizens had a Constitutional right to vote since 1865, many Southern municipalities installed difficult and discriminatory voter registration procedures.

In our small town, the registration process was that two specific women could register anyone if these two women were together in one place — a grocery store, city park, or sometimes at the City Hall.

My father knew these two persons, and decided to keep his eyes open in case he ever saw them together. One day in 1959, 10 years after he had moved to the town, he saw one of the women get out of her car and walk into the courthouse building. He pulled his car over, got out, and followed her into the building.

There, right in front of him, the two women sat together at a table. He approached them and said, “I would like to register to vote.” They replied, “We don’t know what you’re talking about.” He said, “I know that you’re the two people who can register people to vote when you’re together, so I would like to register to vote.”

They continued to say they didn’t know what he was talking about. One of the women got up and left. The second woman remained, continuing to indicate no knowledge of what he was speaking. After a short time, my father decided to leave, having not been able to successfully register.

He was told that if he did come to testify, the commission would not be able to guarantee his safety.

Unbeknownst to my father, someone inside the courthouse building reported the incident to the federal Civil Rights Commission, created in 1957 to investigate how Blacks were being denied the right to vote through a variety of methods in the South, including what my father experienced.

A couple months later, my father was invited to the state capital of Montgomery to speak to the commission members about the incident. He was told that if he did come to testify, the commission would not be able to guarantee his safety. Understandably, none of his friends, due to fear, decided to join him. So he went on his own.

The commission members included Father Theodore Hesburgh, then president of the University of Notre Dame. After the interview concluded, the commissioners asked my father about his safety. My father said that he was glad to have attended the interview but had a newly elevated worry about his safety. After some thought, he decided to wait until night and drive the 50 miles to his hometown with no headlights on.

It happened to be true that our family moved to Knoxville, Tenn., only two weeks later. Thus, there were no official outcomes from my father’s interview. (The commission made its report in 1959, outlining many ways that Black voters in the South were prevented from voting.) In Tennessee, there were no registration prohibitions, so my father was able to vote once again, and my mother voted for the first time in her life, just beyond the age of 30.

Casey Andersen ’12

Assistant Director of Alumni Engagement

I remember waiting in line for hours outside in the cold of Cleveland, Ohio. I remember a woman wearing a dress made from Barack Obama campaign signs. There was a true sense of companionship.

Holly Ewing

Christian A. Johnson Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies

My first presidential vote was on my 18th birthday, during senior year of high school in Oklahoma. I had to register two weeks in advance, and the clerk at city hall said I was not eligible since I was not yet 18, but I knew the law and the registration form, which said that as long as you were 18 on or before election day, you could vote, so I got to register.

Although all my preferred candidates lost, the act of voting was moving: I was now enough of an adult to be responsible for my participation in democracy.

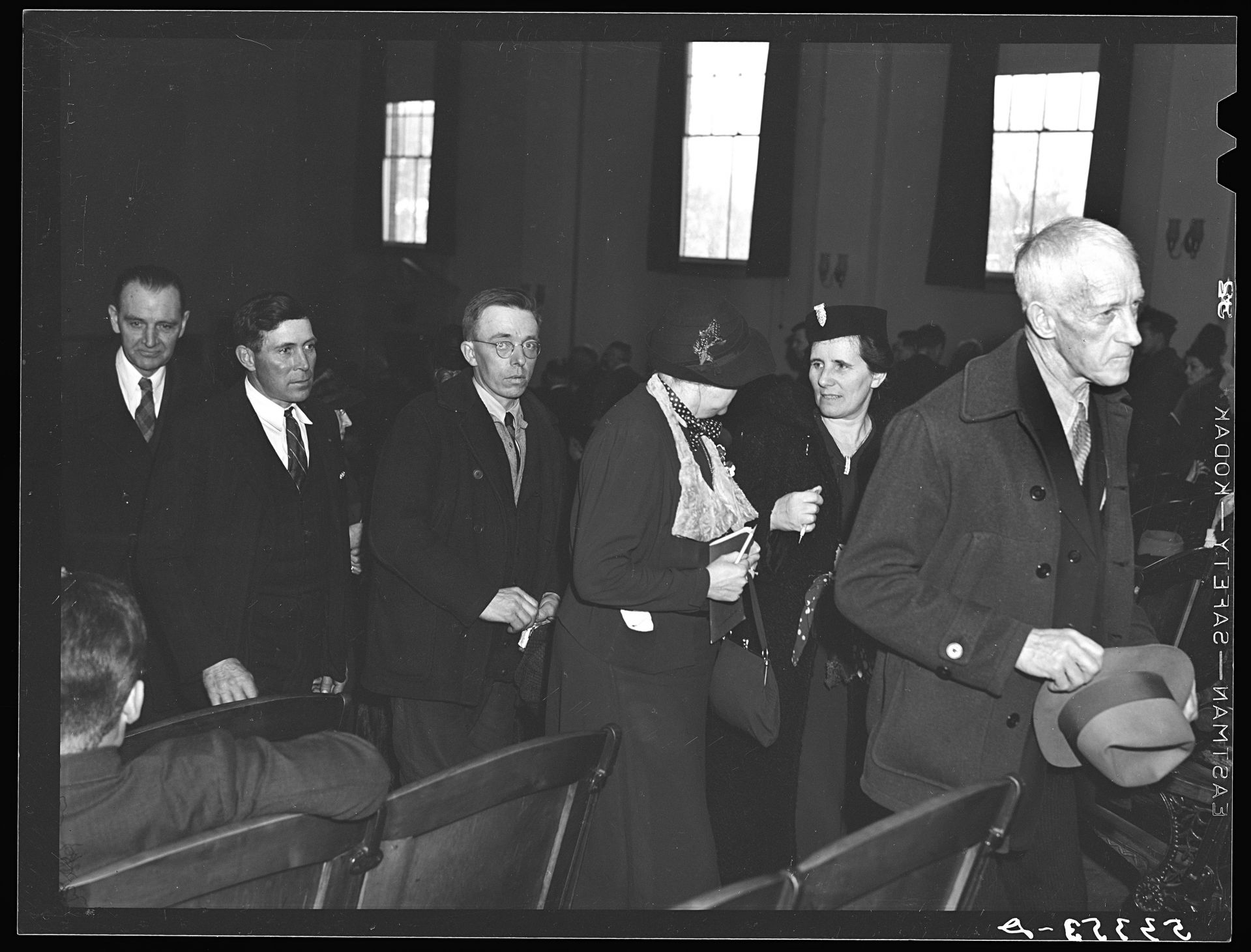

![http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ds.08063

[Three women at a polling place, one looking at a book of registered voters on November 5, 1957, in New York City or Newark, New Jersey] / TOH.

O'Halloran, Thomas J, photographer. Three \women at a polling place, one looking at a book of registered voters on November 5, in New York City or Newark, New Jersey / TOH. United States, 1957. [5 Nov] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2015651653/.](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2020/10/master-pnp-ds-08000-08063u.jpg)

Doug Hodgkin

Professor Emeritus of Political Science

My first vote was at Lewiston’s Martel School in the Republican primary for Maine offices in June 1960. My presidential vote in November was by absentee ballot, as I was in my senior year at Yale. I cut a German class to attend a rally for Richard Nixon at the New Haven Green.

Peggy Rotundo

Director of Strategic and Policy Initiatives, Harward Center for Community Partnerships, and former Maine legislator

I can’t remember the first time I voted, but I do remember that as a child I always accompanied my mother to the polls every November when she voted.

During one of my reelection campaigns for the Maine Senate, a constituent — 92 years old — proudly told me she had never missed voting in an election since she had first registered to vote 70 years ago. Her father, a millworker in Lewiston, had impressed upon her the importance of voting and accompanied her to City Hall when she registered.

To celebrate and to emphasize the importance of this milestone in her life, he with his meager earnings bought her a corsage, which she proudly wore for the rest of the day. I loved the idea of celebrating this rite of passage. When I accompanied my own children to City Hall to vote, we went out for lunch after to celebrate!

Marcos Pacheco Soto ’24

Student from Santiago, Chile

My first election happened to be the most important election in the past 40 years of Chilean history. It was just recently, on Oct. 25, 2020, when Chileans voted overwhelmingly to tear up the dictatorship-era charter in favor of a new citizen-written constitution.

Voting in this plebiscite was meaningful to me because it was a pure example of democracy as it came from the people’s incessant unrest against inequality, elitism, and structural oppression. I saw myself and friends in Chile and all over the world traveling from afar to their consulates and polling places, amid a pandemic, to vote because taking part in toppling Pinochet’s legacy has been the popular struggle of many generations.

Peter Osborne

Associate Director of Career Exploration and Pre-Law Advising, Center for Purposeful Work

I was a college junior when I voted absentee for Barack Obama in 2008. It was my first presidential election and my first time voting ever. I remember the excitement and the strange anxiety I felt when I requested my ballot, received it, and mailed it in. I realized how serious a responsibility it was for me to vote. I take it even more seriously now and encourage everyone I come into contact with to vote!

Glen Warner

Custodian at 280 College Street, Facility Services

My first opportunity to vote for president was in 1976. I grew up watching my dad vote in all elections, whether local or national. As if this wasn’t enough of an incentive, my eighth-grade civics teacher lit the political fire that still burns strongly within me.

As I entered the voting booth for the first time, little did I realize I would also be choosing my first commander-in-chief, as I enlisted in the Navy the following year.

Jimmy Carter was my choice over his Republican opponent Gerald Ford. Though I thought Ford deserved a second chance, I couldn’t get over the fact that he had pardoned Richard Nixon. Looking back maybe I should have voted for Ford. The Carter Administration was a dismal disaster. But as we have recently heard, “Elections have consequences.”

I would encourage all who have the opportunity to vote. To quote one of my idols, my father, “If you don’t vote you have no reason to complain.”

Angus King

U.S. Senator from Maine; 2014 Martin Luther King Jr Day speaker

My first presidential vote was in 1968 for Hubert Humphrey — and some guy from Maine named “Edmund Muskie.” Richard Nixon won that election by fewer than one vote per precinct nationally, a fact that I’ve never forgotten and often use to remind people why their vote is so important.

My clearest memory of that election was of a rally at the airport in Richmond, Va., just before the election. (I was in law school at the University of Virginia at the time). Muskie — who I had barely heard of and never seen before — spoke to the crowd next to the plane. For some reason, I was in the front row. To this day I can’t explain it, but when he finished speaking, I spontaneously shouted, “We trust you!” It was an instinctive reaction to his honest demeanor and authentic connection to the audience.

And little did I know that 45 years later, I would assume Ed Muskie’s seat in the U.S. Senate.

Emily Levine

Director of Parent Giving, College Advancement

I turned 18 on Election Day 1988. I was excited about my first year of college (and about the birthday cake my parents had sent me that day through dining services), but I was thrilled about the opportunity to vote. I had arranged for a mail-in absentee ballot.

Some of the people I voted for won, and others didn’t. I was familiar with the top race — president, as well as gubernatorial and U.S. senate races in my home state — but other races led me to learn about elected offices and candidates I hadn’t known about before. It was an amazing feeling to be part of something bigger than myself by casting my vote.

Frank Daggett

Catholic Spiritual Advisor, Multifaith Chaplaincy

The first time I voted, by absentee ballot as a college freshman, was memorable because everyone I voted for, from president of the U.S. to minor town office, lost! The only exception was a county “race” where the candidate was unopposed.

But instead of becoming disillusioned, I got more involved, voting in every election and frequently communicating with candidates and elected officials between elections.

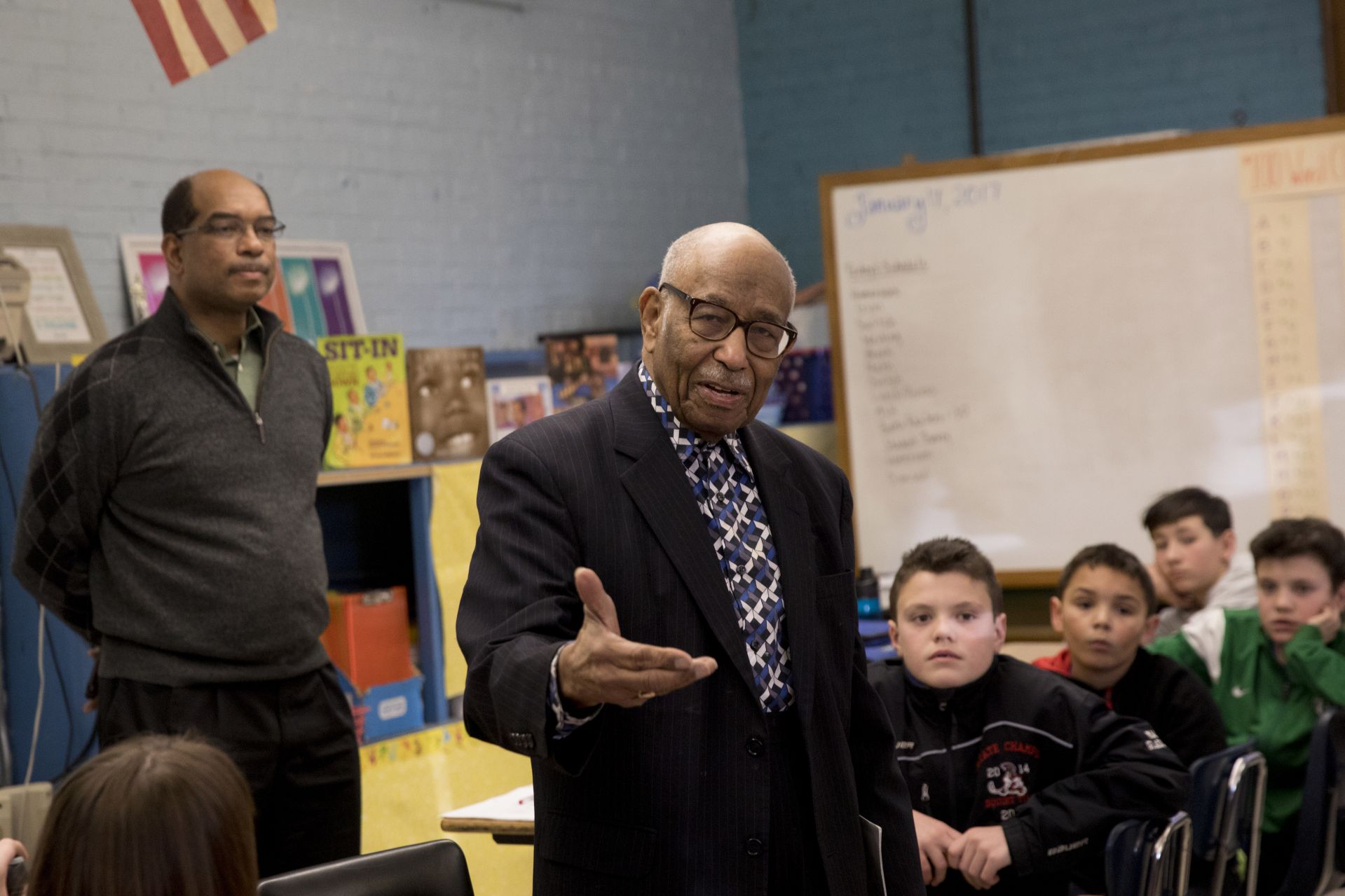

![Negro voting in Cardoza [i.e., Cardozo] High School in [Washington,] D.C. / [MST].SummaryPhotograph showing a young African American woman casting her ballot.Trikosko, Marion S, photographer. Negro voting in Cardoza i.e., Cardozo High School in Washington, D.C. / MST. Washington D.C, 1964. Nov. 3. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003688167/.](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2020/10/master-pnp-ppmsca-04300-04300u.jpg)

Loring Danforth

Dana Professor of Anthropology

In 1972, Americans were bitterly divided by the Vietnam War. It had already cost the lives of far too many Vietnamese and Americans. Richard Nixon had been president for four years and was running for reelection with vague promises of “Vietnamization,” “Peace with Honor,” and the continuation of seemingly endless negotiations with the government of North Vietnam. Running against him was George McGovern, a strong opponent of the war who promised to bring an immediate end to the war.

A few years earlier as an undergraduate, I had applied for conscientious-objector status, as a result of my strong opposition to the Vietnam War. I had drawn a low number in the draft lottery and had come close to being drafted. By November 1972, I was a graduate student in anthropology, living in Athens, Greece. I felt deeply alienated from the U.S. and was eager to begin a new life in Greece.

As election day drew near, however, I also felt very American, and I was deeply committed to voting for George McGovern and against U.S. involvement in the war. In order to vote, I knew I had to go to the U.S. Embassy in Athens, a building I tried to avoid because I always associated it with diplomats and spies.

I steeled myself, entered the building, and made my way to the appropriate office. As I cast my ballot for George McGovern, I wondered for a moment whether the embassy staff would open my ballot, see who I voted for, and throw it away. But as alienated as I felt at the time from American politics, I think I still had enough faith in the democratic institutions of my country to be confident that my vote would in fact be counted.

In the end, Nixon won by a landslide. But the only state in the country that Nixon had not carried was my state, Massachusetts. Two years later, when President Nixon resigned as a result of the Watergate scandal, bumper stickers appeared all over the state: “Don’t Blame Me. I’m from Massachusetts.”

I was proud of my state, I was proud of myself, and I was proud of my vote.

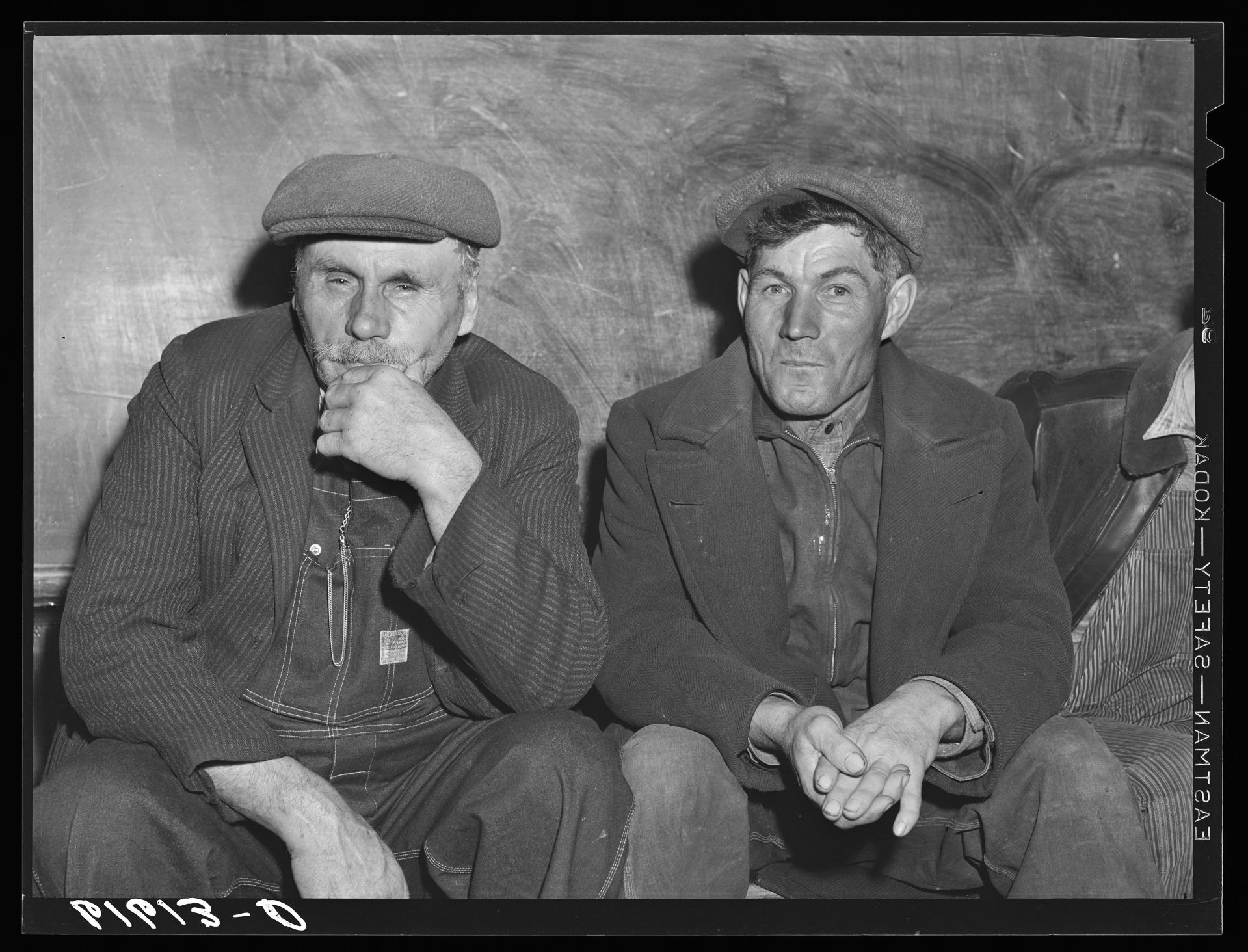

![[African American demonstrators outside the White House, with signs "We demand the right to vote, everywhere" and signs protesting police brutality against civil rights demonstrators in Selma, Alabama] / WKL.

Leffler, Warren K, photographer. African American demonstrators outside the White House, with signs "We demand the right to vote, everywhere" and signs protesting police brutality against civil rights demonstrators in Selma, Alabama / WKL. Alabama Selma Washington Washington D.C, 1965. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014645538/.](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2020/10/master-pnp-ds-05200-05267u.jpg)

Lauren Ashwell

Associate Professor of Philosophy

My first presidential vote was the day I’m writing this: Oct. 19, by absentee ballot, dropped off at Portland City Hall!

When I became a U.S. citizen in 2018, I certainly did not expect my first presidential vote to be absentee, in the middle of a pandemic. I have saved all of my voting stickers from primaries and from the midterms, including the one given to me by the League of Women Voters when I first registered that says, “Watch Out! I’m a Voter!”

This year, there was no sticker as a physical reminder, but I’m extremely grateful to be able to vote.

Cary Gemmer ’07

Leadership Gifts Office, College Advancement

My first presidential election was 2004, Bush vs. Kerry. I remember feeling proud and significant — I had just turned 18 a few months prior, was two months into my college career at Bates, and voted for the first time at the Lewiston Armory. I remember that election season vividly — I had also gone to a rally with John Edwards, when he was a rising star and hero in politics. I was so young, yet felt like I could have a real impact. I was inspired by messages of hope and change.

Jerryanne LaPerriere

Clerk, College Store

Having been born in October, I was one of the few high school seniors old enough to vote in November 1971 when the voting age changed from 21 to 18. It was a day that I will never forget. I was so proud to be able to vote and haven’t missed an election since.

Michelle Greene

Assistant Professor of Neuroscience

My first presidential election was Bush vs. Gore in 2000. On election night, I was so nervous because no winner had been declared. I walked over to the student newspaper office at midnight, naively thinking they would have better information. They were just refreshing the CNN homepage every 30 seconds like I was, but it was good to be uncertain together.

Mary Pols

Media Relations Specialist, Bates Communications

It’s 1984, and I’m voting in Durham, N.C., where I’m a student at Duke. I’ve chosen to vote there rather than my native Maine because notorious conservative Jesse Helms is up for re-election and I want to vote against him.

I’m in a public school gymnasium, somewhere in the city, and I’m in the line, knitting and feeling overwhelmed with patriotism because I get to vote in this election and because Walter Mondale, while entirely uninspiring to me, has selected Geraldine Ferraro to be his running mate, making her the first woman to share a presidential ticket.

Mondale lost and Helms won, but I remember the dim light in that gym and warm colors, the kind that feel like fall all year round, and realizing I might cry a little from the emotion and the privilege to have a voice. This still happens to me every time I vote.

![Photograph shows Margaret V. Lally at the door of a voting booth during the first election where women could vote, New York City. (Source: Flickr Commons project, 2016)

Bain News Service, Publisher. Ready to Vote. , 1918. [March 5] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014706759/.](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2020/10/master-pnp-ggbain-26500-26590u.jpg)