It is no secret that swimming is a predominantly white sport. I experienced it differently, though, as a kid growing up in Bowie and Bethesda, Md.

When I first started swimming competitively at the age of 8, my club team consisted of 90 percent Black girls like myself. That contrasted vividly with my school life outside the pool. I attended a predominantly white elementary school from kindergarten through fourth grade.

As I grew older, my swimming life also became more white as my Black friends dropped out of the sport. And my high school was also mostly white, too.

I became whitewashed, because of the way I grew up in a predominantly white environment in school and, later, in swimming. I was not really acknowledging my Blackness.

Then during my junior year of high school, I heard some of my white peers say the “n-word” for the first time. They were saying it in song, loudly, in our common area where the juniors hung out. That happened a few times, and we brought it up to the administration, and nothing was ever done. I can confidently say nothing is still being done because I know other people who went through the same experience.

It was the first time in my life that I felt a divide between me and my comfort zone. That was when my perspective of my school switched. And as time went on, my perspective of the world around me changed as well.

Weird, in a good way

I was into ballet and swimming from a very young age. My mom, Danielle, was a ballet dancer all the way through college.

I actually stopped dancing in fourth grade because my mom came up to me and was like, “Okay. These two schedules are way too rigorous to do them at the same time. So you need to choose.”

Physically, I was not flexible. I was not that coordinated. It was not working out for me with dance.

Also, I didn’t like to sweat, so I chose swimming. Plus, my younger sister, Jillian, was getting into swimming, so that motivated me even more.

My mom always said that swimmers are “weird,” in a good way! Our sense of humor is kind of different than a lot of the people I have encountered. That may be attributable to the rigorous schedule we go through pretty much our whole lives. We go through hell together, all the time.

We swim twice a day, two or even three hours each session, always exhausted. It brings us closer together as friends. That struggle also shapes who we become.

Not accessible to all

Unfortunately, the history of swimming is pretty racist.

Simply having access to a pool is a challenge for many Black people. Most of the public pools in this country are in predominantly white neighborhoods.

People think swimming is an inexpensive sport, but it’s not if you’re a competitive swimmer. Excluding team fees, the equipment itself: suits, goggles, caps, all the things in our equipment bags. There’s at least 10 items in there that are all expensive on their own, so much so that I didn’t want to buy new things for my senior year at Bates.

Then you add on the expense of being part of a team, and the expense of going to meets and being able to travel to meets in the first place. It’s not accessible to everyone.

I am not sure if that can be altered because we live in a capitalist society. But that is definitely a huge factor holding back many Black people in swimming.

Another structural impediment to Black people, especially girls, is the size of swim caps.

The size of the caps do not vary much. During my first year at Bates, I had to cut my hair because my hair wouldn’t fit in the cap, and not everyone is willing to do that. People of color who have braids or dreadlocks, they don’t do well with caps because their hair is too long or takes up too much space for the cap to handle. I think it has to do with the cap material, because they break pretty easily.

Sometimes I wonder if that is one of the reasons my swim teams became whiter and whiter as I grew older. For Black girls and women, our hair is especially important, and the chlorine from the pool water can do a number on one’s hair. When you are eight years old, that isn’t a big deal. But as you grow older, the way you present yourself becomes more important. I was lucky, as my hair did not react very much to chlorine, but for a lot of Black girls and women, the chlorine can cause hair to fall out.

As you might expect, I never thought about these issues as a kid growing up in love with swimming.

A fading naivete

I entered both high school and eventually college naive to many things when it comes to my Blackness and how it relates to the world.

Hearing my white peers in high school saying the “n-word” started to change that. Trump’s election my senior year also had a big impact. I viewed not only the administration but my peers differently because a lot of them were of age to vote, and most of the people who were of age to vote in my class voted for Trump.

It was just shocking. The Maryland/D.C. area is not necessarily liberal, but I thought it was more aware than a lot of places. Now it was more, “Where am I?” I realized that I didn’t know a lot of the people as well as I thought I did.

Despite all that happening, I still wasn’t embracing my Blackness. High school has so much stress to begin with, from SATs to college applications. Plus there was the swim team, my own little bubble. I was a chameleon, blending in with my white environment.

‘I’m not going to bleeping Maine’

Speaking of college applications, my friend Sally Harris Porter ’21 was a swimming teammate of mine in high school. During senior year, she was admitted to Bates during Early Decision and was excited to row for the Bobcats.

She grilled me for probably over a month. Every time she saw me, “Did you apply to Bates? Did you apply to Bates?” And I was just like, “No.” It was the fact that it was in Maine. I just kind of shut it out. I was like, “No, I’m not going to [bleeping] Maine. It’s way too cold.”

At lunch one day, she just put her computer in front of me and said, “Look at the website and apply.” I was like, “All right, fine. Is this going to stop you from asking me? Because then I’ll apply.” So I applied and I ended up getting in without visiting. I may have emailed the coach just because I was applying. So then when I got in, I went to visit and that’s when I fell in love.

I was considering attending Fordham, where I would not continue my swimming career, or Bates, where I would. Once I had a meal with the Bates swim team, the choice was easy. PC (head coach Peter Casares) was so welcoming. My visit totally sold me on Bates.

I went into college not really knowing much about Bates as a school, and really only knowing it as a swim team. I was shocked — in a good way — by the Bates culture at first, because I was going in like I had in high school. Just going in full force, not really paying attention to racial issues or issues in general. I just focused on my friend groups and my classes and swimming.

I studied abroad in Denmark during the fall semester of my junior year. I was having so much fun on the other side of the world but I was also very much missing Bates and my friendships. It was nice to miss something that much.

I came back to Bates from abroad for the winter semester, then COVID hit, so we got sent home.

A divided summer

Over the summer, with the country already dealing with a deadly virus, the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the police really slapped everyone in the face. Police brutality is still a big problem in this country. Black people knew that already, but it appeared to open a lot of white people’s eyes to the issue. And with COVID, people had time to focus on police brutality and on racial equity in general. That includes issues of racial equity at Bates.

Our swim team at Bates is the best, most welcoming group of people I have ever been around. But being separated by COVID and everyone going home in March was really difficult.

One of the issues we encountered over the summer as a team was being at our respective homes meant that each of us viewed the events happening nationally surrounding George Floyd and Black Lives Matter through very different lenses. It was very divided over the summer.

If somebody was brought up in a household that has a culture of white supremacy, and they’re in that environment while all this is happening, their viewpoint about Black Lives Matter and George Floyd is going to be shaped by the people around them.

I tried to remind myself about that when we had our team Zooms and talked about what was happening nationally with race. Whether we’re talking about a new topic we’re all learning together, or we’re talking about an incident that happened, or somebody’s bringing up a question, I try to keep an open mind.

Even though I am a person of color and I’ve been through certain experiences that other people may not even realize, I don’t know all the answers. I don’t know where anybody else is coming from. So for anyone, especially myself, to have a closed mind, I think that is ridiculous because why would you not want to learn?

Because of the way some of my teammates seemed to view BLM and the protests, I was very nervous for our team’s dynamic in the fall. But we are doing much better now.

We had a very long Zoom meeting the first semester. I think it was about two hours long. It was a Zoom meeting where I shared my mental health struggles surrounding some important interpersonal issues. It was basically me pouring out all of my feelings onto this Zoom with 60-plus people.

I had no idea if all of them were actually listening and appreciating what I was doing. I felt very vulnerable to begin with, but also I felt appreciated by the seniors I was sitting with during the meeting. So, while I felt appreciated by the people around me, I also felt like certain people weren’t really listening. And those were the people I was trying to get to listen.

So I ended that Zoom being kind of frustrated and hurt, because it was my personal story that I was sharing and my experiences that I was sharing. And I didn’t feel heard by everyone.

But one person actually texted me after the Zoom and said, “I have a few questions. Can I call you and ask?” And I was like, “Oh, of course.” I almost started crying because I was excited. “Oh my God. This is working already.”

I had a conversation with that teammate and it was very beneficial and he learned things. I learned things, too, about him that I hadn’t known before. He just didn’t want to say them in front of 60-plus people, which I totally get. Both parties learned a lot and a barrier was broken down.

Our coaches, Peter (Casares) and Vanessa (Williamson ’05), are here for me and I love it.

They both reach out a lot to check in on me. After team Zooms, they see how I am doing because a lot of the Zooms can be taxing. The coaches have also been doing a lot of learning, which I’m so proud of and I’ve noticed it pretty significantly.

I don’t think I’ve had coaches who were so fast to be on board with things that weren’t specifically about swimming. Coaches are always like, “You can come to me for everything, whatever you need I’m here.” But, I never really took that literally. I kind of just was like, “Oh, they’re being nice, whatever. Swimming is swimming, I’ll come and I’ll swim and I’ll move on with my life.” I can really go to Peter and Vanessa for literally anything, and that’s just an amazing feeling.

I think we are definitely on the right trajectory as a team, but it’s going to take some time.

‘You’re not seeing me’

Because I grew up the way that I did, I didn’t really acknowledge my Blackness for a long time. Now that I am embracing it, and learning more about myself, it’s something that’s really important to me.

When people say ‘I’m color blind, I don’t see color.’ Oh, then, you’re not seeing me. You’re not seeing who I’m growing to be, or who I want to know is me. One of my pet peeves is when people say they’re color blind.

I have realized how easy it would be to go through Bates without encountering any type of class on race, or even classes that help you understand why people are the way they are, in a sense that it kind of gets rid of entitlement a little bit, or at least pokes at entitlement.

I’m a psychology major, so that’s been my whole life at Bates. Great classes are there if you seek them out.

In fact, right now I am taking “Race and U.S. Women’s Movements” with Visiting Associate Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies Melinda Plastas. Another impactful class I am taking is Discipline, Race, and Schooling with Associate Professor of Education Patricia Buck.

But I am now realizing that you could totally leave Bates without any education on racism or how people interact, which I think is extremely important to have in the real world. It’s not just about getting a degree.

An anti-racism class requirement would be a great start, but it can’t be a “check the box” course for Bates students. I know that’s how I see taking a science course. I don’t really pay attention. Hopefully, an anti-racism course does not end up like that because we’re not talking about chemistry, we’re talking about people’s lives.

Agents of change

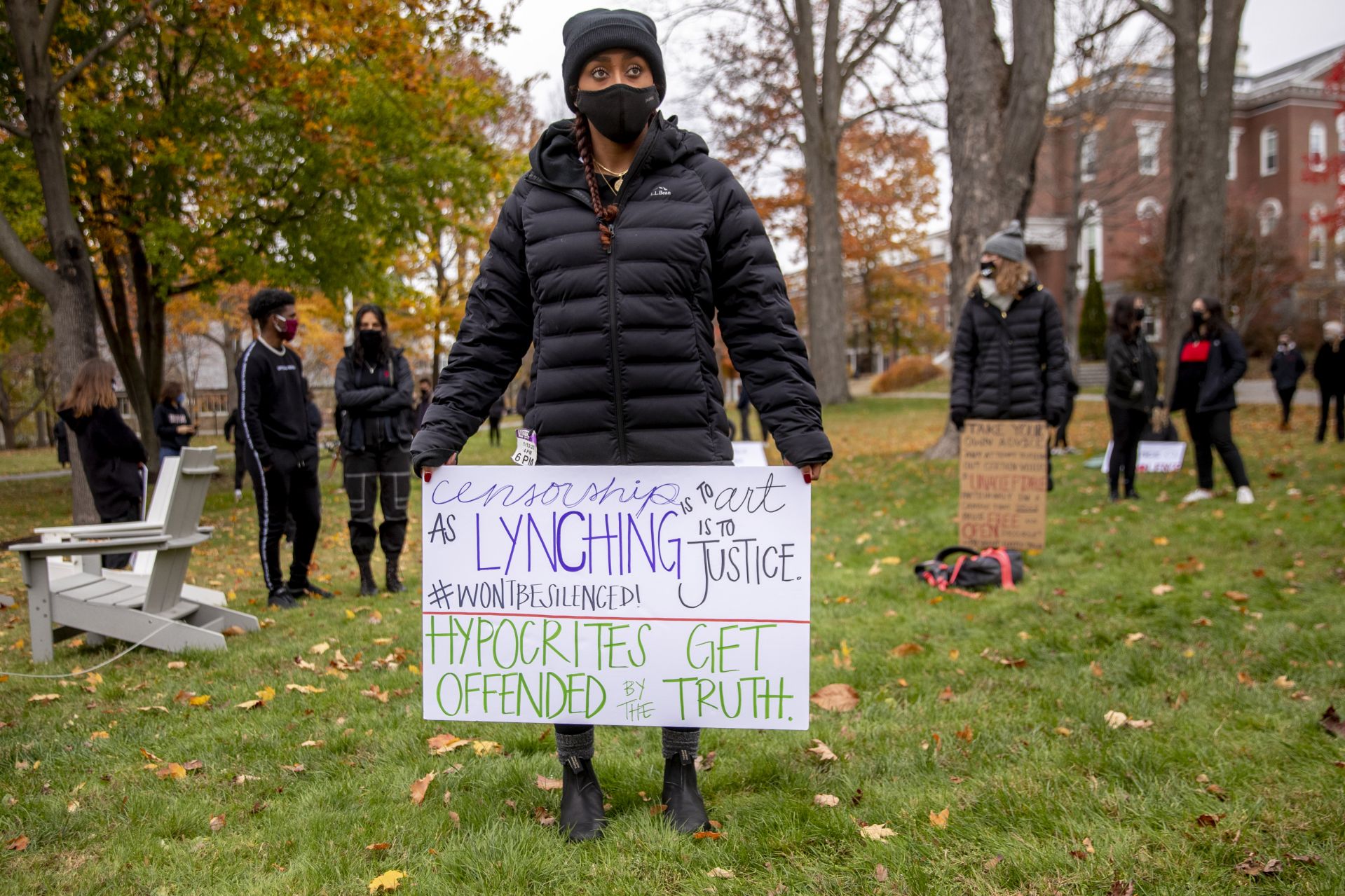

Over the summer, a number of student-athletes, including myself, realized we needed to band together for much-needed change. The Bates Athletics Agents of Change and the Bates Athletes of Color Coalition are brand new groups in partnership with the Athletics Department, and I hope they have an impact for years to come.

But we are in a delicate spot. I don’t think a lot of Bates athletes are even aware of these groups right now. In particular, the Athletes of Color Coalition is supposed to be a support group for athletes of color to feel welcome. Head football coach Malik Hall is passionate about it and I love it, but there’s only so many emails we can send. I hope that in the next two years, these groups are known to everybody on campus.

The student-athletes who started the groups are mostly seniors. I’m afraid that once we graduate and once the political environment around Black Lives Matter, police brutality, and injustice dies down, this spirit of activism will also die down. I’m really hoping it doesn’t. Assistant Athletic Director of Student-Athlete Services Jess Duff is really invested in it and I have faith because of her.

In terms of changes I am looking for moving forward, it all starts with recruiting. I would like to see more athletes of color at Bates and not athletes of color in stereotypically Black sports. We need more Black swimmers, more Black rowers.

On top of that, I don’t know how many people know this but there is a divide between students of color and student-athletes of color on the Bates campus, mostly because of the inability to hang out with a lot of people outside of your team because of practice schedules. That needs to change.

These groups within Bates Athletics are in their infancy, but they have already shown me ways that sports psychology and social justice can go together, which is something I had not realized.

Now I’m thinking more about the sports psychology course I took, and my thesis actually has to do with sports psychology. I’m looking at the way athletes view themselves based on their experiences because of their race. I haven’t really decided if I want to look at all sports or look at specific sports that may be more stereotypically Black or more stereotypically white.

My thesis advisor is Su Langdon. She helps me come up with more questions to ask myself about what I want to look into, which has been great. I’ll go to her and say “Okay, now I want to do this,” and she’s like, “No, look further.” I won’t lie, that can be frustrating! But it is also very helpful.

‘Now I wonder why….’

To me, embracing my Blackness means that I am more aware now of the things that people who look like me go through on a daily basis and I am more aware of the things that I go through on a daily basis because of my skin color.

I reflected back on my swimming career this past summer because of everything that was happening and because my friends and I had been talking about racism in the sport of swimming. It was definitely a topic of conversation in my household as well.

At first, I couldn’t think of anything. Then as the summer went on I kept remembering events that happened that I hadn’t realized were problematic at the time, but were certainly problematic.

One memory in particular stays with me.

When my club team was predominantly Black, when we warmed up for meets we would all go behind the blocks together and there would be other swimmers from other club teams. The lanes weren’t assigned. So it didn’t really matter where we went, but because we were all friends, we went to the same places together.

So there would be this big group of Black girls behind the blocks and then the adjacent two lanes would empty. The white kids would just leave the lanes. This happened a lot.

My team was called Central Chesapeake, so we called ourselves “Peak” for short, and we thought it was great, an area all to ourselves! We would just be like, “Oh, the Peak lane. Ha ha ha. That’s so fun.”

But now, I wonder why those white kids always left.

As told to Aaron Morse of the Bates Communications Office. Photos courtesy of the Boucree family. Additional photos by Theophil Syslo, Phyllis Graber Jensen, and Brewster Burns.