For many people, the idea of standing under the spotlight and reciting lines to a dimly seen audience is a daunting task.

Now imagine giving an onstage monologue in a mask that hides your mouth and muffles your every word, forcing you to speak louder, enunciate more clearly, and breathe more deeply. No easy task, right?

Facing the uncertainty of a pandemic while following rigorous COVID-19 protocols — including masks and physical distancing — this year’s theater majors took to their tasks with determination, successfully completing directing or acting requirements in three live plays staged this spring, the college’s first live performances in over a year.

Bates theater returned to the stage in March with A Gaggle of Saints, directed by Patrick Reilly ’21 of Mendham, N.J.; Grand Concourse, staged in April; and Twelfth Night, directed by Deon Custard ‘21 of Chicago and now in performance at Schaeffer Theatre.

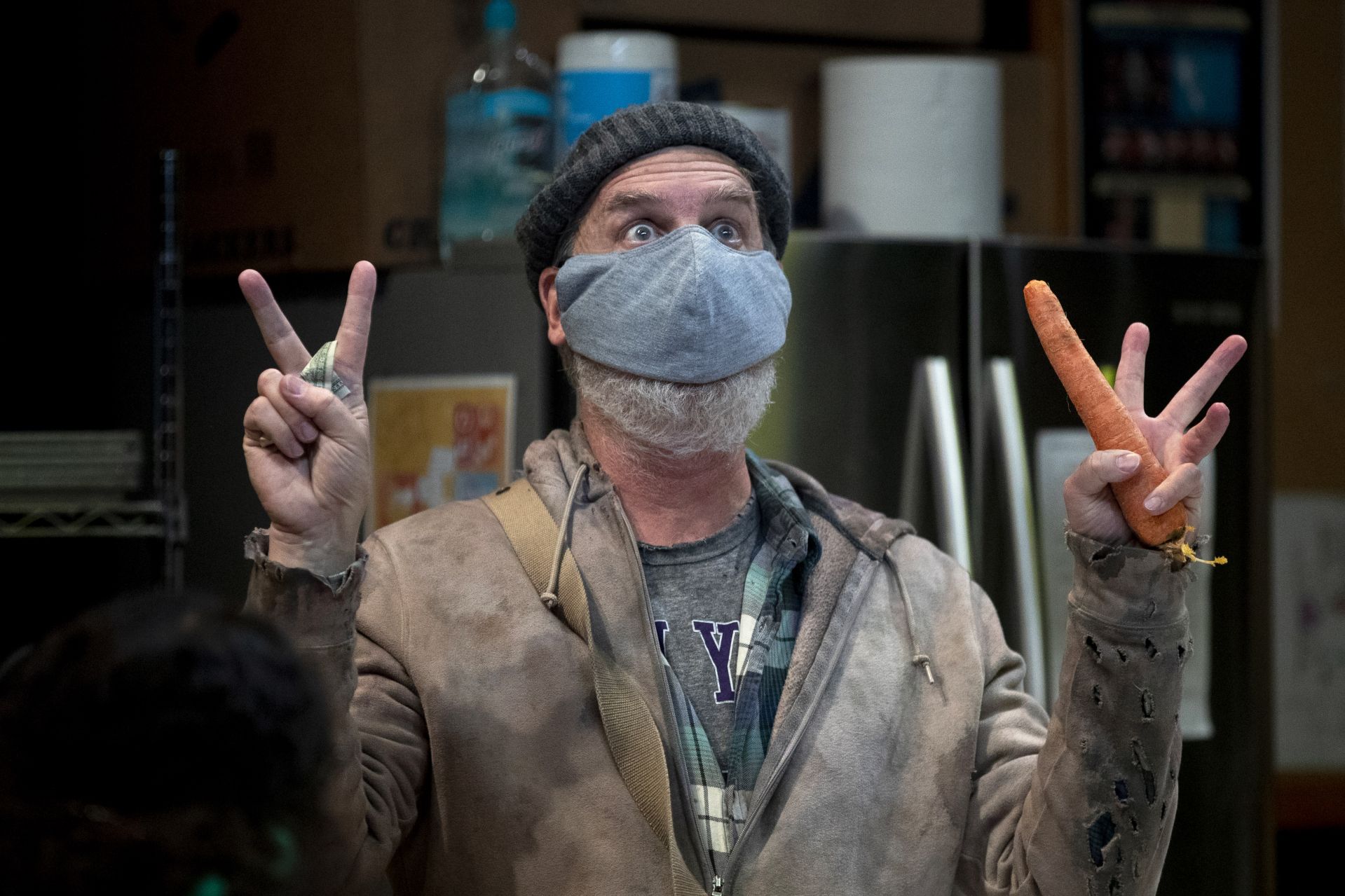

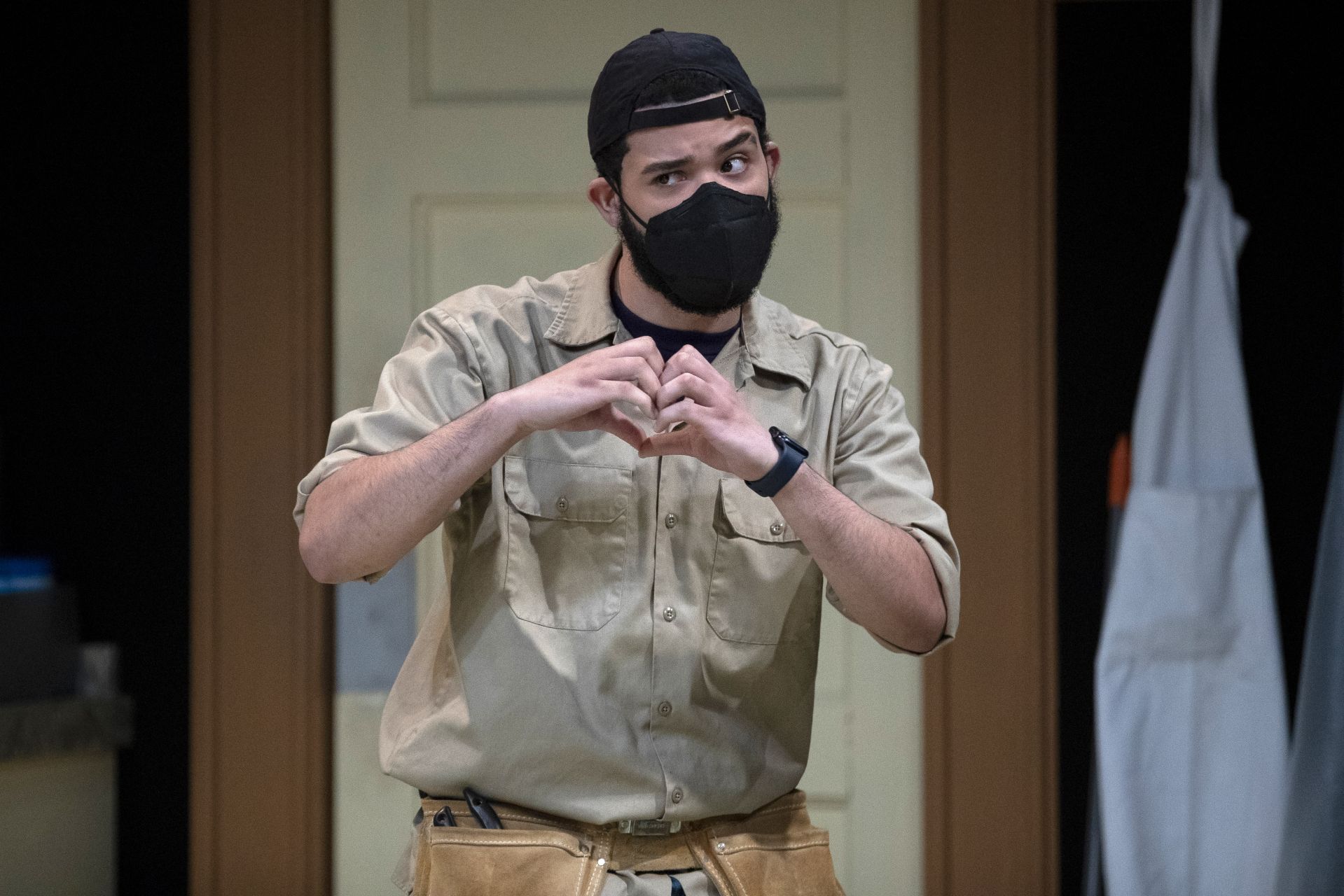

Recently I spoke with three key figures involved in Grand Concourse — director Nicky Longo ’21, actor Perla Figuereo ’21, and their advisor, Lecturer in Theater Cliff Odle — about the challenges, and unexpected rewards, of doing live theater in a pandemic. The cast also included Professor of French and Francophone Studies Kirk Read, Dawrin Silfa ’21 of New York City, and Emily Diaz ’23 of Corona, N.Y.

Nicky Longo: When a hug is not a hug

When Longo proposed Grand Concourse as his senior thesis in directing back in February 2020, he had no way of predicting the pandemic’s impact. However, his choice ended up being fortunate because actors wearing masks was a good fit with the play’s setting, a soup kitchen in the Bronx.

“We as a cast were basically like, ‘OK, this play will be set in the COVID time.’ It’s a soup kitchen, so it kind of made sense that the people working there might be wearing masks to protect their food, themselves, and the people they’re serving,” said Longo, who is from Cambridge, Mass.

While the play itself didn’t require much suspension of disbelief with COVID, Longo was challenged in restructuring some of the logistical elements. “I would always show up to rehearsal early or stay late the night before and think about a scene we were about to do, like ‘OK, they’re supposed to hug here, how do you evoke the same things that a hug does without a hug?’”

Longo is also a major in psychology, and he drew on lessons from that discipline when working through the challenges of directing masked actors. For one, he knew that his audience of mostly Westerners would likely have trouble interpreting the emotions of masked actors.

In Western societies, including the United States, “people often interpret someone’s emotions by looking at the mouth,” Longo said, referencing a 2007 study on the topic. On the other hand, the study found that people in Asian cultures focus more on the eyes than the mouth when interpreting others’ emotions.

“So here we are doing a play trying to convey emotions and now we’re restricted to only using our eyes,” Longo says. “That was definitely a challenge.”

The solution to this lay not just in channeling emotion through actors’ eyes, but throughout their entire bodies. “What we tried to do was really focus on gesturing,” Longo said.

He especially relied on the dance talent of one of his actors, Dawrin Silfa ’21 of New York City, to emphasize full-body expression. “We were able to use his ability to be confident in space to physicalize emotions with our whole bodies, not just our mouths.”

In the end, Longo firmly believes that the constraints and adjustments made possible the theater department’s in-person existence. “Masks afforded us a safe way to come back together in this space and make live theater for people. We were just so fortunate.”

And what the pandemic took away in terms of physical proximity, it also provided, through Zoom, greater access to external resources, including a Zoom visit with Grand Concourse’s playwright, Heidi Schreck, and Kip Fagan, who directed the play’s world premiere in 2014. “I don’t know if we would have been able to do that without Zoom in our lives,” Longo says.

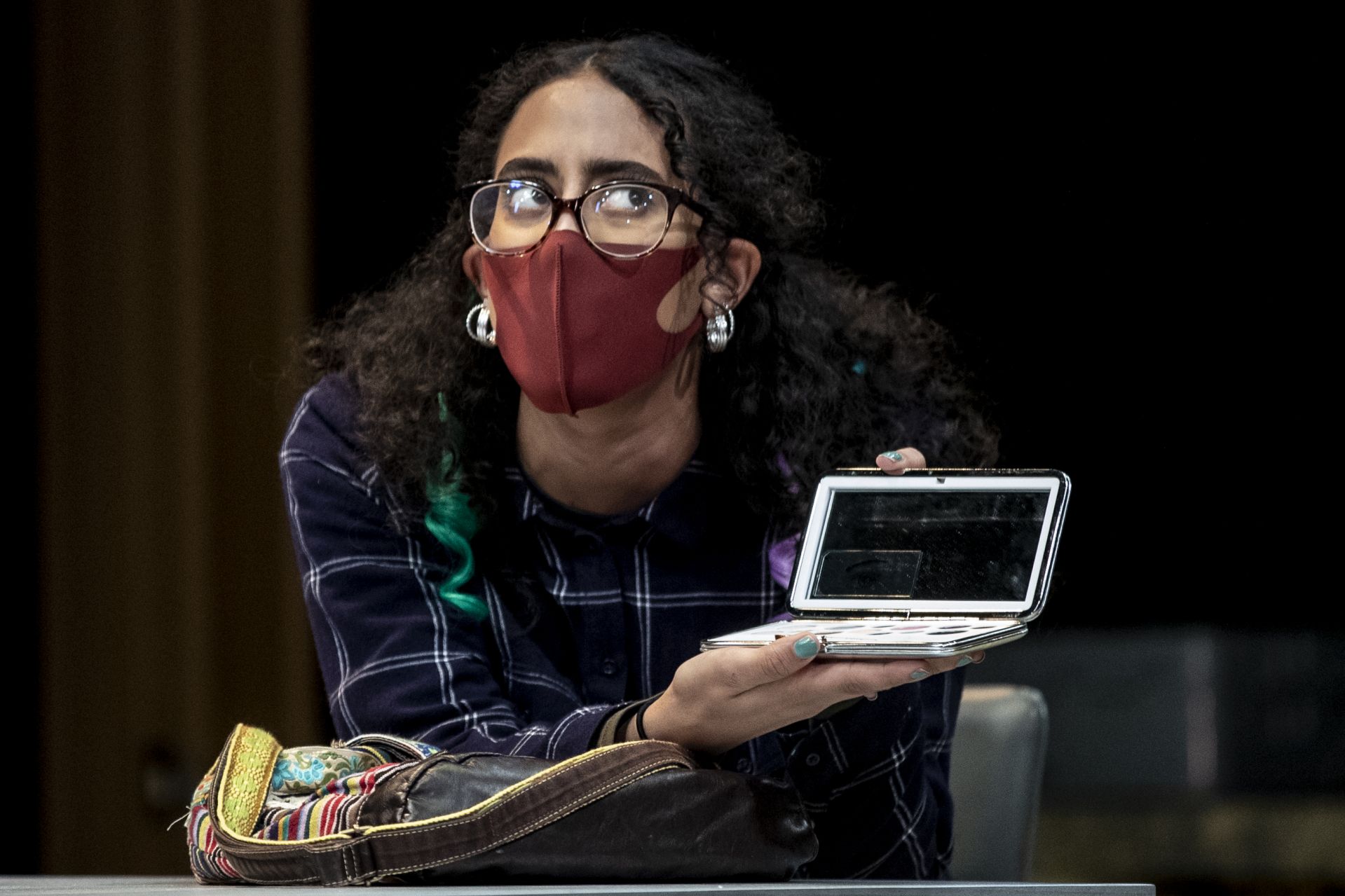

Perla Figuereo: When eyes become the face

For Figuereo’s senior thesis in acting, she played Grand Concourse’s lead role, a 39-year-old nun named Shelley who runs a soup kitchen in the Bronx. The role involves multiple monologues and requires highly emotional acting, both of which were made especially difficult with the use of masks.

“For me, enunciation was extra important because my words could easily get muffled into my mask,” says Figuereo, who herself is from the Bronx.

“When I would practice in my room, I would practice with a mask on. Not only was it a challenge of just acting, but a challenge to make sure people heard me.”

In the play, Shelley is pushed to the breaking point emotionally. “I had a lot of scenes where I had to cry,” Figuereo says. “I think my eyes became my face. If I was annoyed, I would roll my eyes or if I was scared, I would bunch my eyebrows.”

Like many actors, Figuerio can cry on command. For her, “it has to do a lot with breathing,” she says. But during her masked-up Grand Concourse scenes, tears weren’t enough. So in one scene, she collapsed onto a desk, and then onto the floor, making her character’s sadness a full-body experience.

The way a blacksmith needs a bellows, an actor needs strong breathing to make their lines heard. With a mask, “I just had to be more mindful of my breathing. If I didn’t catch my breath, if I didn’t take time to breathe, then I would drown in my own mask,” she said.

“It wasn’t the hardest thing in the world, I just had to be more mindful of pronunciation, breathing, and body language.”

Despite the difficulties, Figuereo says that acting with a mask had silver linings. “It made our stage presence even better because we all have to use our bodies and our eyes to communicate the story.”

Although Figuerio envisioned her senior thesis differently and was saddened that her family couldn’t see her perform in person, she said she was happy with her role and felt that she learned from the challenges it posed. “I feel like I am a better actor now because of the people that surround us,” she said. “It ended up being such a fun journey.”

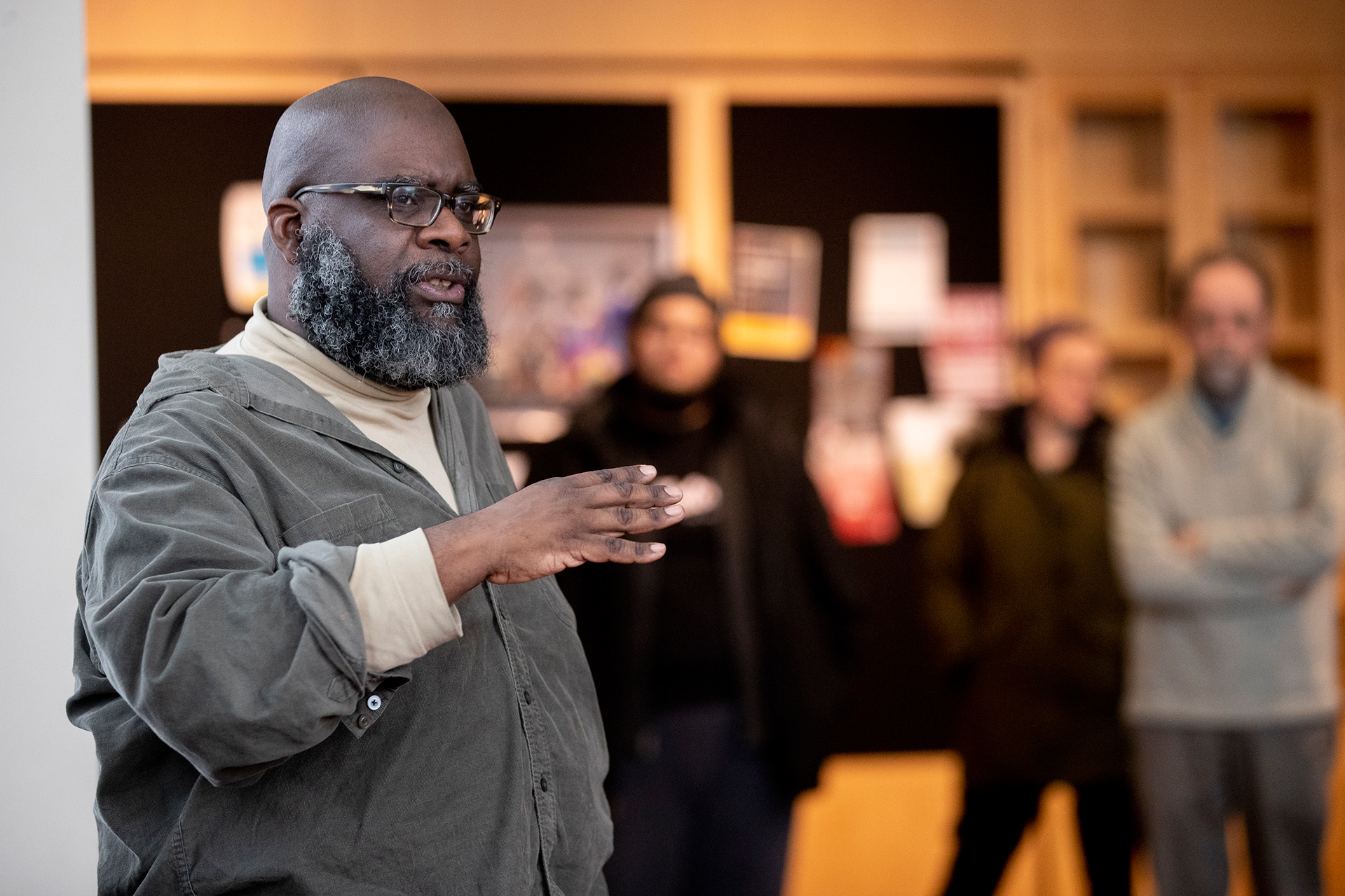

Cliff Odle: When you come out from the wilderness

A theater faculty member who advises a senior thesis in directing is a guide on the side. “It’s a lot of checking in, monitoring, and giving advice,” says Odle. “It’s making sure the student has what they need in order to have the best production possible.”

Like all other aspects of college life during a pandemic, the mise-en-scène involved in staging Grand Concourse required additional guidance and problem-solving. “It was a very intricate dance to keep people safe,” Odle says. One example was placing a large island in the soup-kitchen set to ensure actors’ physical distancing.

“Part of the challenge was remembering you can’t get too comfortable,” said Odle of the actors’ adjustments to wearing masks. “You have to project the idea that you’re comfortable on stage, but you actually can’t get too comfortable because as soon as you do, it’s easy to lose your voice. You’re not as articulate, you’re not as vocal, and the mask will expose all of that.”

And, of course, there was the ever-present threat that live theater would simply not be possible at all in 2020–21, whether due to a campus COVID outbreak or external disruption. The possibility that the show would end up being presented on Zoom “was always in the back pocket,” Odle says.

“When it comes to how we do the work under these conditions, we were in the wilderness,” Odle said. “So, the fact that they were able to do it is just awesome. The fact that there was a show with live people is a win, when a lot of professional theaters have not been able to do anything like that.”

There’s no doubt, Odle says, that Bates theater will carry forward the many lessons learned this year — whether about projection while acting with masks or how to deal with day-to-day uncertainty. “People are able to pull together under very difficult circumstances, and that’s an experience you carry with you.”