In a wide-ranging discussion that felt like a salon, a group of Bates scholars gathered the other day to talk about the courage and energy it takes to transgress — to cross the assumed boundaries of their teaching and scholarship by engaging in topics of racism, white supremacy, and unequal structures of power.

They were invited to the gathering by Associate Professor of Africana Sue Houchins, the recipient of this year’s Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching.

Charles Nero, the Benjamin E. Mays ’20 Distinguished Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies, moderated the discussion, titled “Courage to Transgress: Engaging Dangerous Ideas in the Classroom.”

Houchins set the scene by referencing the book Teaching to Transgress by the late bell hooks. “The title makes it clear,” said Houchins, “that our vocation is to instruct students in the practice of pushing back against what is normative, what is safe.”

Houchins explained how, in hooks’ career as a scholar, teacher, and activist, she exposed the “interplay of race, capitalism, gender, and…their ability to produce and perpetuate systems of oppression and class domination.”

Which is what’s happening at Bates, said Houchins. Funding from a $1.2 million grant from Andrew W. Mellon Foundation is helping the faculty “to excavate in the archeologies of our various disciplines so that we can transform our curriculum and change our pedagogical approaches to better align them with our institutional values and goals around equity and inclusion.”

“At that moment, I realized that there was a price that I paid for my particular interest and desires.”

The best teachers, hooks wrote, “had the courage to transgress those boundaries that would confine each student to an assembly line approach to learning.”

Looking at the colleagues she had invited to be panelists — Assistant Professor of Biology Lori Banks, Associate Professor of Religious Studies Alison Melnick Dyer, Assistant Professor of Digital and Computational Studies Anelise Hanson Shrout, Assistant Professor of Classical and Medieval Studies Mark Tizzoni, and Nero — Houchins said that each have “reputations for just this kind of courage.”

Nero, for example, recalled his first semester in his Ph.D. program at Indiana, when “three professors asked me a variation of the same question, ‘Why are you interested in that Black stuff? Hasn’t everything been said and written about Black people?

“At that moment, I realized that there was a price that I paid for my particular interest and desires.”

A generation younger than Nero, Banks did her undergraduate studies at a historically Black university, Prairie View A&M. Unlike what generations of BIPOC students have experienced at predominantly white institutions, Banks and her peers were spared from being told, overtly or otherwise, that Black students lacked the “intelligence or ability when it came to the practice of science or medicine.”

But as she emerged into academe, Banks came to learn how “historical narratives within our scientific community have excluded the contributions of women, people of color, openly queer folks. Those narratives were not true — it was just that we were all being exploited and somebody else got the Nobel Prize.”

For example, Angelina Fanny Hesse, wife and sometimes-lab assistant of microbiologist Walther Hesse, never got credit for her contributions that led to Robert Koch’s Nobel Prize in 1905.

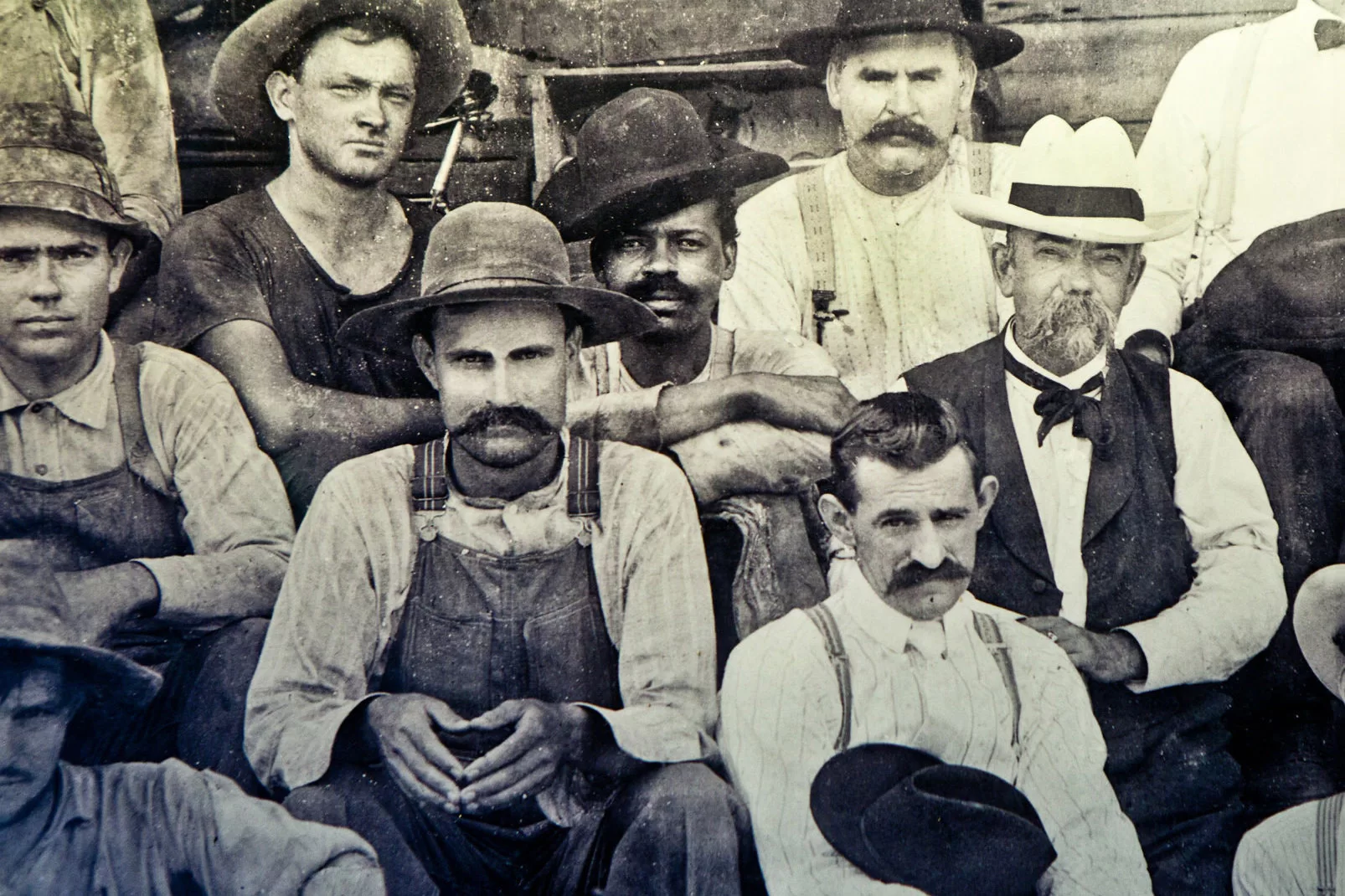

Such lack of recognition isn’t limited to the upper echelons of science. Jack Daniel’s is a household name in whiskey, but it was Nathan “Nearest” Green, an enslaved person, who taught a man named Daniels how to make whiskey. The whiskey company describes Green as a “friend” or “mentor.” “But neither of those terms really applies given the power differential associated with human ownership,” said Banks.

Banks was frank about the net effect of centuries of unequal power structures: It means that “we’ve been lying to our students about who does science,” she says. “I want to fix that and I want to squash those narratives. That’s how I approach my pedagogy.”

Students come to college with a preconceived idea of who is a successful scientist. It’s a kind of “idol worship” of a stereotypical idea — think Neils Bohr, Albert Einstein, and Watson and Crick — of “who you’re supposed to be, what kind of music you’re supposed to listen to, and how you dress, and who you love.”

But in real life, Banks says, “all of these things are not the same for everybody who practices science and medicine.”

Dismantling preconceived notions takes courage, which Banks was feeling that day, having just watched The Woman King. (The movie reference got a round of applause. “Go see it,” said Nero.) “I acknowledged a long time ago that these were going to be difficult conversations,” she said. “I kind of just take a deep breath and go for it.”

There is, of course, immutable scientific knowledge. As a colleague of Banks’ noted, “the Krebs Cycle doesn’t change because you went to a different institution.”

Melnick Dyer, whose teaching includes Buddhism and other Asian religious traditions, said, with a laugh, “It turns out that how people think and talk about Buddhism absolutely changes depending on what institution you’re in.”

Which means that students arrive with all kinds of “misunderstandings about religious traditions that are perpetuated through histories of cultural appropriation and adoption and adaptation.”

If so, asked Nero, how does a professor, especially one who does not have tenure, navigate these waters with students who might be uncertain about hearing something new?”

“I’ve been thinking about this a lot,” Melnick Dyer said. Confronting a student’s misunderstandings can help them “confront their own privilege and perhaps other things they might find very uncomfortable.”

But that carries risk. A student unhappy about being pushed toward a new way to understand Asian religions can vent about the professor on a course evaluation, and that “directly relates to how we perceive our own precarity or our own safety as educators.”

But “we can get around this,” she said. When introducing difficult topics in the classroom, it’s key not to ambush a student. “Invite them into the conversation,” by clearly introducing upcoming topics, like privilege, cultural appropriation, and even the students’ relationships to the cultures and traditions they’re learning about. Placing them in context can help encourage interest and engagement, rather than leaving students feeling alienated.

In Shrout’s courses in digital and computational studies, often the most uncomfortable discussion is the one about the highly problematic historical relationship between statistics and eugenics, as many early statisticians were eugenicists.

“I don’t mean that in a hyperbolic sense,” said Shrout. “These were men that actually believed that they should develop statistical models to study humans so that they could figure out who should die. That’s really uncomfortable.”

But as long as a student feels safe in the discussion, creating discomfort is important.

Students who understand the history of statistics and eugenics are going to be better prepared to “engage with their field and a career than if they could just pretend that these dudes — who Hitler loved, by the way — were just distant figures on a pedestal devoid of social context.”

Shrout has noticed a shift in the conversations and questions about how “the ways in which white supremacy and settler colonialism and these other structures of powers have shaped the disciplines that we’re in.

First was resistance: “It doesn’t belong in our curriculum.”

Second, ambivalence: “How do we shoehorn it in?”

Third acceptance: “This is the thing we should be thinking about.”

Finally, transgression and action: “What have I been missing by not thinking about this? How do I rectify that?”

Nero who asked the scholars how they engage in transgression in their fields, “with our peers who are immediate, as well as our peers who are beyond this institution.” The question’s answer, he said, does require a certain amount of handling, “gingerly,” since a scholar’s reputation is at stake.

In response, Tizzoni spoke about his forthcoming book, which takes a new view of the history of Roman and post-Roman North Africa, a region known after antiquity as the Maghreb.

Scholars of the ancient Maghreb often viewed it through a Eurocentric lens, divorced from its African contexts. Tizzoni will embrace an African and Indiginous orientation, raising questions of colonization, resistance, and racialization. He expects the text to generate some controversy becaus “the people who trained me would expect me to think about ethnicity instead of race,” he said.

And though his field of premodern studies is beginning to consider its “complicity with white supremacy and the construction of modern systems of white supremacy, it is hotly contested right now.”

Because he and his students study history from 1,000 or 2,000 years ago, there’s a lot of prior scholarship that can’t be accepted at face value. The author of a well-known book on Latin language, Gildersleeve’s Latin Grammar, Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, was a Confederate soldier who remained “unrepentant and pro-slavery for the rest of his life,” said Tizzoni.

“Students need to know the ways in which foundational figures within the discipline were problematic,” he said. “We need to read these texts knowing that that has happened. The danger really is in continuing to pretend that it didn’t because it did, and it’s all there.”