Older alumni might recall Mount Gile in Auburn as a recreation spot featuring a ski slope, a destination on the Stanton Ride, and where a stone monument marks a 19th-century tragedy.

The Mountain

Soaring 545 feet above sea level, Mount Gile sits in East Auburn across the Androscoggin River from Lewiston, about 3.5 miles from campus. Mount David, by comparison, is 381 feet high.

The Person

The mountain is named for Edwin Tuttle Gile, an Auburn businessman who in 1884 bought 12 acres of land atop what was then called White Oak Hill.

Having already invested in the city’s first trolley (pulled by horses), Gile wisely leveraged that business interest by creating a trolley destination on the outskirts of town: his hill, which he turned into a destination for citizens seeking a relatively new offering of the Gilded Age of America, leisure and outdoor recreation.

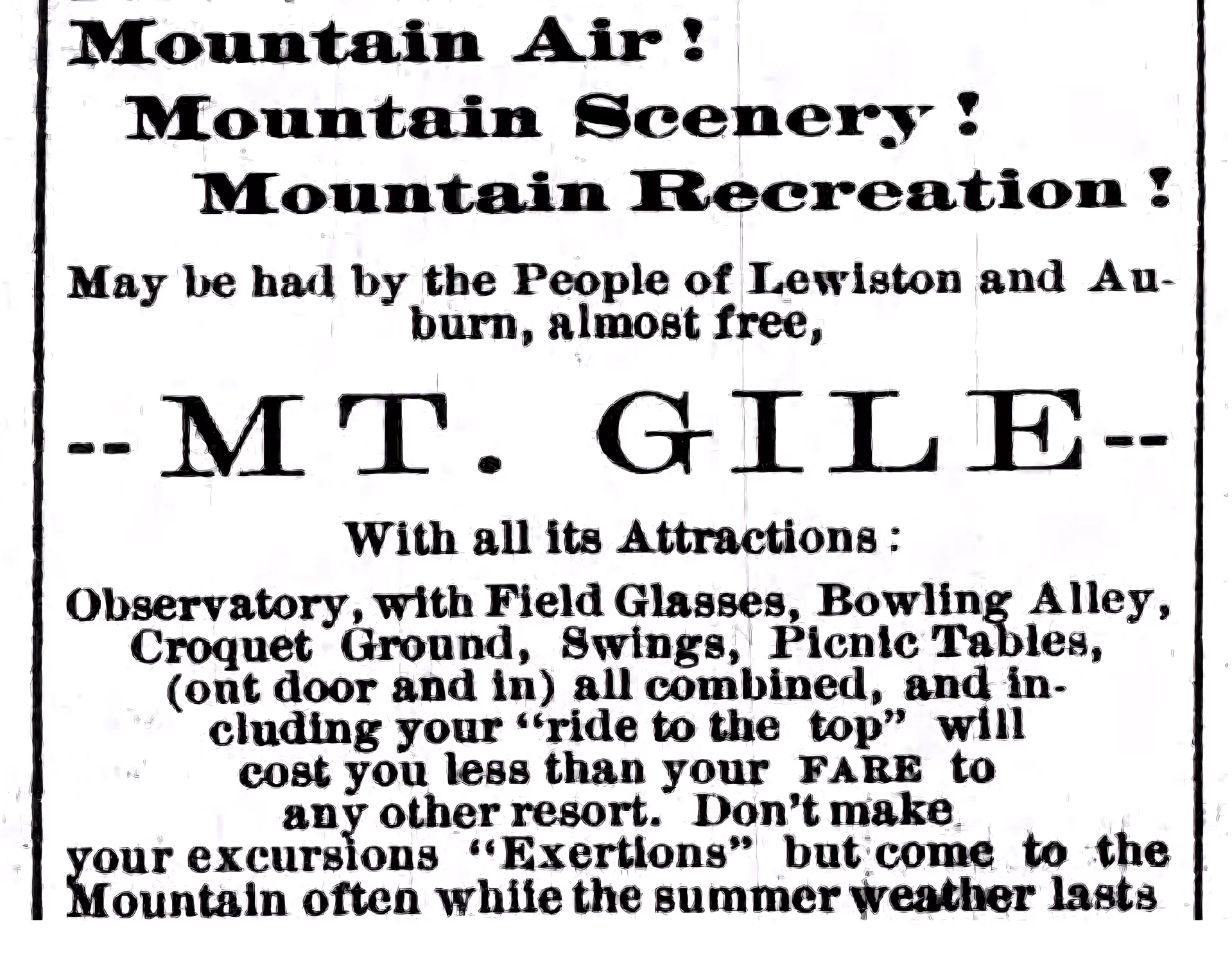

A Lewiston Evening Journal ad in 1886 promised “Mountain Air! Mountain Scenery! Mountain Recreation!” The site included a croquet court, picnic tables, and, in the words of an 1890 edition of The Bates Student, “a little observatory with the stars and stripes fluttering above it in the breeze.”

The Ski Slope

In the early 1960s, the East Auburn community created a ski slope at Mount Gile with a 550-foot rope tow. Small-town ski slopes were hardly unusual in the mid-1900s — Maine had 80 or more.

The Bates Connection

Into the early 1900s, legendary Bates professor Johnny Stanton brought each incoming class on a trolley ride from campus to Lake Grove Park, a bygone picnic and recreational area along the shore of Lake Auburn. From there, he led students on a hike up Mount Gile, followed by a meal.

After his death, the tradition of an outdoor outing during orientation became known as the Stanton Ride.

The Tragedy

In 1866, a 22-year-old woman named Louise Greene was asked to leave her school, the Maine Wesleyan Seminary and Female College (now Kents Hill School), after being accused of theft.

Rather than return to her home in Peru, Maine, she traveled by stage to Auburn and committed suicide by poison, her body was found on Mount Gile.

Her father, who mounted a vigorous public crusade claiming her innocence, erected a monument where her body was found. Atop a stone base, it is about 5 feet tall and surrounded by an iron fence. He also published many “pamphlets” in her defense. The inscription on the memorial says, in part, that she was the victim of unkind people and a “martyr to the prejudice and caprice of man.”

On the south side are these words, presented in Greene’s voice: “Heart breaking, dearly beloved, adieu.” On the north side, again in her voice: “I could have died for one friendly hand-grasp and thought it happiness to die.”

From the early 1900s to the 1960s, the monument was a stopping point on the annual “Stanton Ride,” the outdoor orientation trip for first-year students led by legendary professor “Uncle Johnny” Stanton and later by Dean of the Faculty Harry Rowe.

Gathered around the memorial, the new Bates students heard all about the girl and her fate. Stanton and Rowe ended the story with this moral: “So you see, it always pays to be kind.”

Today

In the news lately is the possibility of some land on and around Mount Gile being rezoned for potential housing.