During the last week of classes for the fall semester, two instructors, two classes, and one rabbit gathered together for an interdisciplinary, interactive first-year seminar class session.

It was easy to tell who was from which course. Students from “Beyond the Rainbow: Exploring the Language (and the Science, Art, and Culture) of Color” had all walked in sporting colorful hats. Joining them in a classroom in Dana Hall were students from “Sex in the Brain: The Neuroscience of Sex, Gender, and Hormones.”

While it is typical for students to grow close in these small — 16 students maximum — seminars, this merging of the courses for a class session was a new idea, meant to create new connections between both the subjects and students as the semester came to a close.

Lindsey Hamilton ’05, director of the Center for Inclusive Teaching and Learning, and Wells Castonguay, the center’s assistant director, devised the plan. Castonguay was teaching “Beyond the Rainbow” and Hamilton “Sex in the Brain.” Throughout the semester, each instructor had heard students’ ongoing curiosity about the other’s course and saw an opportunity for the students to learn from each other.

Ina Dobreva ’29 of Sofia, Bulgaria was in “Sex in the Brain,” while her friend Celina Carman ’29 of Buenos Aires, Argentina, was in “Beyond the Rainbow,” and the two had often talked about the similarities between their two courses.

“We were saying every time, ‘We have the same course, just in a different font,’” Dobreva said.

Both courses were highly interdisciplinary, as first-year seminars (FYS in Bates speak) are designed to be. “Sex in the Brain” explored everything from neuroscience to endocrinology to human behavior, while “Beyond the Rainbow” focused on subjects like physics, neurobiology, and language.

When the classes came together, it was a lively scene, with students swapping knowledge, playing games, and petting Patience, Castonguay’s foster rabbit, who lounged in a playpen. (Patience, not a regular visitor to the class, was making a special appearance to celebrate the end of the semester.)

All first-year Bates students are required to take an FYS. As entry points to Bates’ rigorous and diverse curriculum, the courses aim to transition students to college-level writing and set them up for academic success. FYS instructors serve as advisors to their students until they declare their majors.

FYS offers students an opportunity to take a class in a field that might be new and unfamiliar to them. In fact, students shouldn’t necessarily take an FYS related to the subject they plan to major in, Hamilton explained. “It really doesn’t matter which topic you get,” Hamilton said. “You learn so much in critical thinking.”

Hamilton is speaking from experience — both as an instructor and a Bates alumna. When she arrived at Bates as a first-year student, she was “laser-focused” on neuroscience, until the liberal arts curriculum introduced her to interdisciplinary possibilities.

“As I took other courses, I started to get really excited,” Hamilton said. “My own FYS here at Bates was awesome.”

With small class sizes, first-year seminars also play an important social role for new Batesies.

“We all became friends over the course of the semester,” said Wynn Harward ’29 of Erie, Penn., a “Sex in the Brain” student. “I look forward to class every day.”

The FYS students shared what they’ve learned with their peers during presentations on each course. First, “Sex in the Brain” students Dobreva, Harward, Regan Clute ’29 of Tahoe City, Calif., and Sofia Rossi ’29 of Memphis, Tenn., gave a presentation about behavioral differences between sexes. They dipped into their knowledge of both hormones and societal gender expectations to explain how sex differences are biologically, socially, and culturally based.

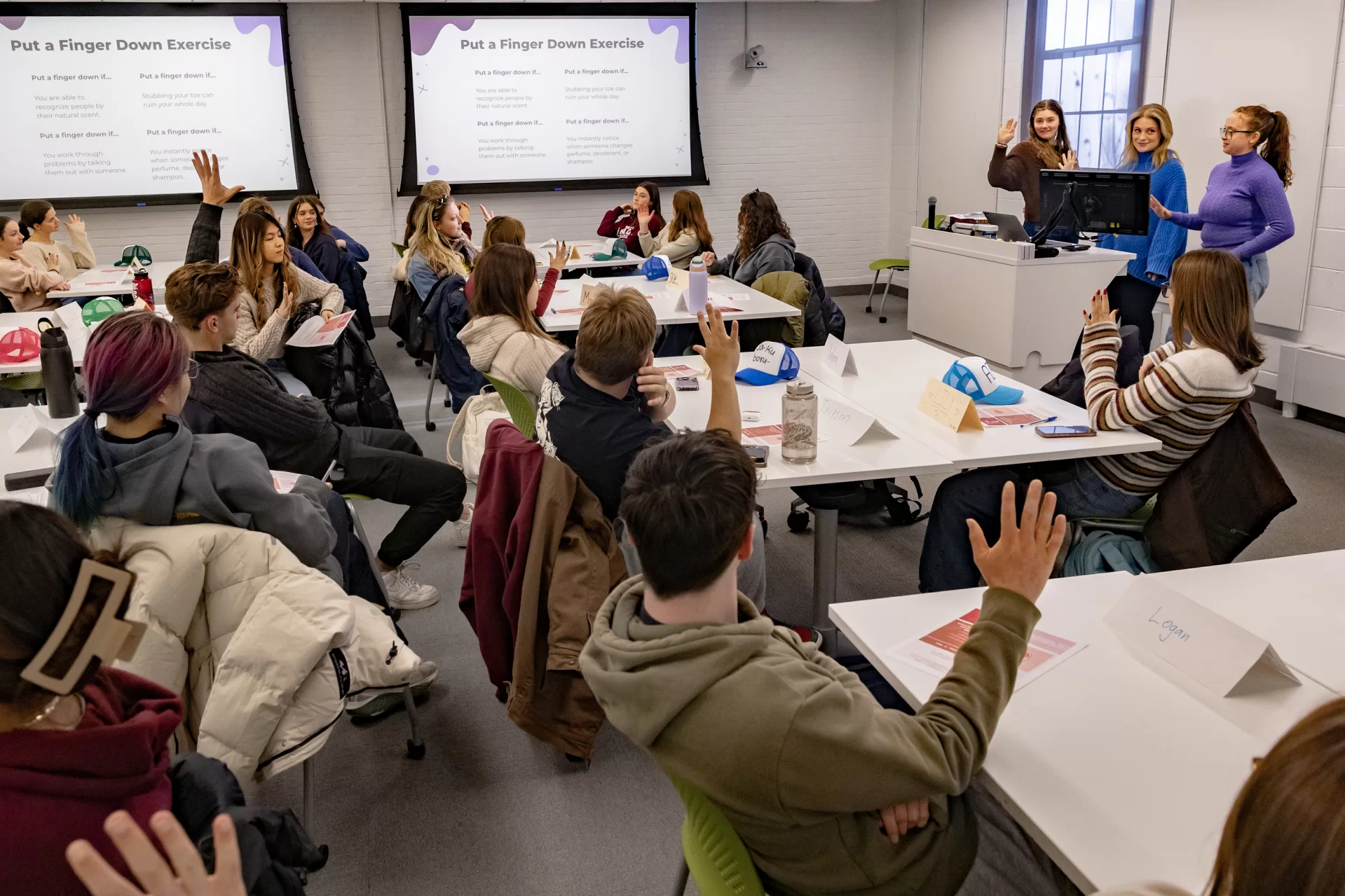

The students demonstrated sex differences by reading a list of behavioral traits and asking peers, with their hands in the air, to lower a finger for each trait that they felt represented them, such as, “Put a finger down if you instantly notice when someone changes perfume, deodorant, or shampoo.”

At the end of the activity, there was a clear divide: far fewer fingers were left standing among the female-presenting students.“It was really interesting to see — even with something that seems almost ridiculous, but it is topical — there really is a difference,” Clute said.

Then Ruby Wiley ’29 of Chagrin Falls, Ohio, Skye Pearlman ’29 of Harrison, N.Y., and Evelyn Hoskins-Hynek ’29 of Silver Spring, Md., gave a presentation about “Beyond the Rainbow” for the other students, covering everything from the eye’s rods and cones to how language impacts perception of color.

To demonstrate the latter, the presenters asked their peers to redraw and rename color boundaries from those of the typical ROYGBIV spectrum created by Isaac Newton (that’s red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet). Students got creative with the possibilities here; one divided the spectrum into five categories with nature-inspired names like “flower” and “grape,” while another divided the spectrum into three colors named after high school science courses: “chemistry,” “biology,” and “physics.”

“Rainbows are just a spectrum of hues,” Wiley said. “There’s also value and chroma and so many countless ways to divide up the color space, which we see in a lot of different languages.”

While presenting, Wiley was sporting a baby blue hat with “neela” (romanized ਨੀਲਾ), the Punjabi word for colors that fall into English category of “blue,” written across the front. The colorful hats were connected to two different assignments from the semester, the first being an essay about a favorite color and, the second, an independent research project.

“A narrative essay about our favorite color sounds simple, but it wasn’t just, ‘Oh, my favorite color is baby blue,’” Wiley said. “It was, ‘Why is it baby blue, and how would you define it? What makes it your favorite color?’ It’s a writing class. We were focusing on our creative writing skills there.”

For the other assignment, students had interviewed someone who spoke a different language to learn about how they categorized color. So, for the final class session, Castonguay brought each student a hat in their favorite color and asked them to write the name of the color, in the language of the person they had interviewed, on the front of the hat, combining the results of the two assignments to offer a glimpse into what the course covered — from linguistics to cultural interpretations of color to personal experiences.

“Wells just made everything enjoyable,” Ruby Wiley ’29 of Chagrin Falls, Ohio, said. “She made sure to make it engaging no matter what we did.”

In preparation for the joint class, all of the students, working in groups, had prepared presentations about the semester. The final groups from each respective class were chosen by their peers to present at the joint session.

Castonguay said that their students didn’t realize just how much they had learned and how many subject areas they had covered throughout the semester until they began preparing the presentation.

“It was fun when they were preparing for this class hearing them say, ‘Wait, I have to teach that. They’re not going to know that,’” Castonguay said.

After the presentation, Castonguay overheard a conversation between one of their students and a “Sex in the Brain” student amazed at everything that “Beyond the Rainbow” had covered. As Castonguay recounted, “they said, ‘You really learned all of that? You learned physics and neurobiology?’”

“Yes,” Castonguay’s student answered. In one semester, they really had learned all of that.

Faculty Featured

Wells Castonguay

Assistant Director - Center for Inclusive Teaching and Learning

Lindsey R. Hamilton Ph.D.

Visiting Lecturer and Director of the Center for Inclusive Teaching & Learning