Biography

Muskie’s Early Life and Family

Stephen Marciszewski (1883-1956) was born in Russian-controlled Poland. Around age 12, he was apprenticed to a master tailor to learn a trade with which he could support himself abroad. At his father’s insistence, Marciszewski left Poland at the age of 17 in order to avoid army conscription. He then spent a few years in England before immigrating to the U.S., where he changed his last name to Muskie because, he said, it was easier for Americans to pronounce. Now a master tailor himself, Stephen Muskie opened his own shop in Rumford, which provided financial stability for his growing family. Decades later, Edmund Muskie reminisced about working in the shop and listening to his father’s political discourses. He described his father as unapologetically outspoken in his support of Democratic Party ideology, even though it conflicted with many of his customers’ own Republican beliefs.

In this recording, Muskie speaks about his father’s political views during an interview on August 6, 1991.

Josephine Cznarnecka Muskie (1891-1973) was the third of eleven children born in a Polish-American family in Buffalo, New York, where her father worked on a railroad. In Journeys, Edmund Muskie wrote that when his parents married in 1911, “she made it clear to him that she couldn’t cook and she couldn’t sew…My father made it clear to her that she would learn …[and]she became superb in both departments.” In an interview with Voice of America in 1968, Josephine Muskie told the story of how she came to Maine as a new bride:

Right after the wedding, the next day, we came to Rumford, Maine. That was supposed to be our honeymoon. My husband promised that he would bring me back to Buffalo, but here it is, 57 years have gone by, and I’m still in Rumford, and my husband is gone, too.

Life at Bates

As a student at Bates College, ‘Eddie’ Muskie—as he was then known—was remarkably active in extracurricular activities, including student government and debate. Professor Brooks Quimby, who led the Bates debate team to national prominence, helped recruit Muskie to Bates and served as an early mentor. As Muskie biographer David Nevin wrote:

The footing that Quimby gave Muskie in debate … had many effects on him, but one of the clearest was that it gave him a structured form in which to escape shyness … The rules of debate forced him into channels with the rest of the contestants, and once he was moving, his quick mind and his developing ability to cut to the heart of an argument were free to rove across the problem and bring up his capacities.

Muskie began college at one of the lowest points of the Great Depression, a fact that nearly ended his Bates education after the first year. In April 1933, Muskie’s father wrote to him and instructed him to bring his possessions home at the end of the semester, as it was unlikely that he would be able to return in the fall.

Bates increased Muskie’s scholarship by $25. In addition to his earnings from on-campus employment as a waiter in Commons and summer employment at the Narragansett-by-the-Sea resort in Kennebunk, this seemingly small amount enabled him to continue his college studies.

After Bates

Cornell Law School, acting through Bates President Clifton Gray, offered Edmund Muskie a scholarship to attend based on the success that previous Bates graduates had there. This was despite the fact that he had not applied, nor even expressed a desire to pursue a legal profession. Muskie accepted the offer, but at the end of the first year of classes, he again found his education imperiled by financial crisis. Muskie learned of William Bingham II, a wealthy man who supported Gould Academy in Bethel, Maine and assisted students who needed financial help to continue school. Muskie wrote to Bingham, and within a few days had an interview with Dr. Farnsworth, Bingham’s agent. Muskie left the meeting with $900 and a promise of $900 more the next year, both interest-free loans.

Cornell Law School, acting through Bates President Clifton Gray, offered Edmund Muskie a scholarship to attend based on the success that previous Bates graduates had there. This was despite the fact that he had not applied, nor even expressed a desire to pursue a legal profession. Muskie accepted the offer, but at the end of the first year of classes, he again found his education imperiled by financial crisis. Muskie learned of William Bingham II, a wealthy man who supported Gould Academy in Bethel, Maine and assisted students who needed financial help to continue school. Muskie wrote to Bingham, and within a few days had an interview with Dr. Farnsworth, Bingham’s agent. Muskie left the meeting with $900 and a promise of $900 more the next year, both interest-free loans.

Muskie joined the Navy in 1942, soon after the U.S. entered WWII, leaving his solo law practice in the hands ofhissecretary. As he related in an oral history interview in 1985: Within a week after I enlisted in the Navy, I don’t know how he learned about it, I got a letter from Dr. Farnsworth enclosing the first note canceled. He said, “I don’t think you ought to go into the service with this burden hanging over you,” and he said, “next year, we’ll return the second,” which he did. In the Navy, Muskie was trained as a diesel engineer and attained the rank of Lieutenant. He served from April 1944 to November 1945 on board the U.S.S. Brackett (DE 41), which was assigned to the Pacific theater of combat. Muskie was discharged from active duty in December 1945, and like many returning veterans, became active in AMVETS.

Jane Gray Muskie (1927-2004) and Edmund Muskie were married for nearly 50 years and raised five children together. When she met Muskie, Jane Gray was a 19-year-old dress shop girl from Waterville whose father had died when she was 12, leaving her mother to support five children by boarding Colby College students. After 18 months of courtship, she agreed to change both her religion (Baptist to Catholic) and her political party (Republican to Democrat) to marry Edmund Muskie. After Jane Gray Muskie’s death, longtime Muskie staffer and friend Don Nicoll reminisced: They were devoted to each other. Their personalities were different, they had a feisty relationship at times, but that never dampened their devotion and love for each other. It was a very impressive marriage.

In this audio clip recorded In 2000, Jane Muskie remembered how her family reacted to the news of her dating an older man and how he eventually proposed to her.

The Muskie family included two young children, Stephen O. (born 1949) and Ellen (now Ellen Allen, born 1950), when they moved into Blaine House in 1954. When they left for Washington after two gubernatorial terms, the family had grown by two: Melinda (now Melinda Stanton, born 1956) and Martha (1958-2006). With the birth of Edmund Jr. (called Ned, born 1961) during Muskie’s first Senate term, the family was complete. Although the younger children spent most of their youth in Washington, D.C., they all spent summers together in Maine, first at Muskie’s camp on China Lake and later at the family’s Kennebunk Beach home. None of the children have chosen to follow their father’s career path in law and politics.

The Muskie family included two young children, Stephen O. (born 1949) and Ellen (now Ellen Allen, born 1950), when they moved into Blaine House in 1954. When they left for Washington after two gubernatorial terms, the family had grown by two: Melinda (now Melinda Stanton, born 1956) and Martha (1958-2006). With the birth of Edmund Jr. (called Ned, born 1961) during Muskie’s first Senate term, the family was complete. Although the younger children spent most of their youth in Washington, D.C., they all spent summers together in Maine, first at Muskie’s camp on China Lake and later at the family’s Kennebunk Beach home. None of the children have chosen to follow their father’s career path in law and politics.

Governor to Senator

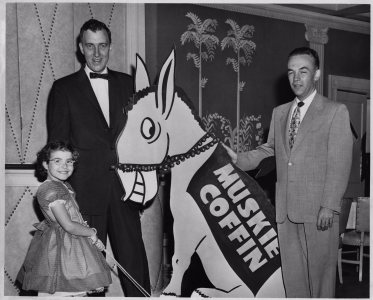

The Maine Democratic Party existed before Edmund Muskie, but his surprising gubernatorial win in 1954 marked a turning point in its history. Muskie was the first Democrat Governor of Maine in nearly 20 years, and only the second in the preceding 40 years. The 1952 election of President Eisenhower, a Republican, triggered a sea change in the Maine Democratic Party. With the national Party’s loss of the White House, Maine Democrats lost the patronage that had sustained their influence for decades, and senior party members began to retire from leadership, creating timely opportunities for younger men like Muskie, Don Nicoll and Frank Coffin. The Democrats had a tough time recruiting someone to run for governor in 1954. After all other potential candidates declined, Muskie, a former state representative who was still recovering from the physical and financial effects of a broken back he suffered in 1953, reluctantly agreed to run. Hard campaigning and an intimate knowledge of the state gained during his direction of the Office of Price Stabilization paid off for Muskie when he surprised nearly everyone by winning. His election was so noteworthy that it earned him momentary national attention, including an appearance on NBC’s Today show and a spread in Life magazine. After two successful terms as governor, Muskie made history again in 1958 when he was the first Maine Democrat elected by popular vote to the U.S. Senate.

Staffers in Muskie’s Washington and Maine offices numbered as many as two dozen at any time, not counting the dozens more employed on campaign and committee staffs. Each performed duties crucial to the Senator’s daily success: researching issues, drafting legislation, scheduling, interacting with constituents, answering mail, issuing press releases, preparing speeches, and managing the entire operation. Some of the more well-known Muskie alumni include: • Former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright • Former U.S. Senator George Mitchell • Political commentator Mark Shields • U.S. Representative Tom Allen • Former National Security Advisor Tony Lake

Staffers in Muskie’s Washington and Maine offices numbered as many as two dozen at any time, not counting the dozens more employed on campaign and committee staffs. Each performed duties crucial to the Senator’s daily success: researching issues, drafting legislation, scheduling, interacting with constituents, answering mail, issuing press releases, preparing speeches, and managing the entire operation. Some of the more well-known Muskie alumni include: • Former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright • Former U.S. Senator George Mitchell • Political commentator Mark Shields • U.S. Representative Tom Allen • Former National Security Advisor Tony Lake

Marjorie Hutchinson was first hired by Muskie around 1940 as his law office secretary. She moved to his gubernatorial office in 1954 and then to his Waterville senate office, where she worked until her retirement in 1976. Joan Arnold, who also worked in the governor’s office, told this story about Hutchinson and Muskie in a 1998 oral history: But she not only was the perfect secretary and very bright and charming and capable, she also had a little motherly touch with him, too…I don’t think people would think of him as being receptive to a woman in his office being motherly to him, but he certainly was with Marge…I can remember when photographers were getting ready to go into his office…Margorie was always, always in that office at the very last minute…with a little hair brush, calming the curls down. He had very curly hair, and she would be…getting the hair just so, so he wouldn’t have curls flying all over his head.

The Campaign

The 1968 presidential campaign was the first time that many people outside of Maine and Washington D.C. heard of Edmund Muskie, when Hubert H. Humphrey asked him to join the Democratic Party’s ticket as his vice presidential running mate. Although the Humphrey-Muskie ticket lost to Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew in a very close election, many observers regarded Muskie as the election’s true winner. During the race, he was often viewed more favorably than Agnew, Nixon, or even Humphrey. After the race, he was often looked to as one of the Democratic Party’s rising national stars.

On Election Eve 1970, the Republican and Democratic Parties each purchased 15 minutes of national prime time television, hoping to influence the next day’s midterm elections. During the Republicans’ time, stations broadcast a speech in which President Nixon condemned “a creeping permissiveness in our legislatures, in our courts, in our family life, and in our colleges and universities,” and called for “the great silent majority of Americans . . . to stand up and be counted against appeasement of the rock throwers and the obscenity shouters in America.” Muskie spoke from an armchair in front of a fireplace in Cape Elizabeth, Maine about the need for national unity in addressing racial tension, environmental destruction and economic problems. As Time reported, Nixon appeared “agitated, stern in a noisy setting, and the victim of a bad television tape.” In contrast, the magazine described Muskie’s performance as “calm and concerned, if somewhat theatrical.” The broadcast cemented Muskie’s position as a national political figure who garnered widespread respect and approval.

See Muskies statements made the evening before the election here!

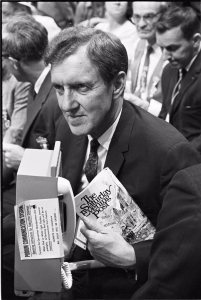

“President Muskie! (Don’t you feel better already?)” was one of several slogans used in the 1972 presidential primaries to contrast EdmundMuskie against President Nixon. Despite leading the list of potential Democratic candidates throughout 1970 and 1971, Muskie’s campaign financing began to falter late in 1971, and by the spring of 1972 he was effectively, if not officially, out of the primaries. Popular memory holds that Muskie’s campaign collapsed following an angry, impromptu and allegedly teary late-January press conference in front of a Manchester, N.H. newspaper that had insulted his wife, Jane, in print. As Madeline Albright, who first worked for Muskie as a fundraiser on this campaign wrote in her 2003 autobiography: Today a male politician who cried while defending his wife would probably go up in the polls. In 1972 men were not supposed to shed tears in public, especially when running for president. In reality, though, the reasons for Muskie’s loss were more complex. With strong grassroot and youth support, and benefiting from Nixon “dirty tricks” against Muskie, George McGovern won the Democratic primary, but lost to Nixon in one of the largest landslides in the history of presidential elections.

See a clip of one of muskies presidential campaign adds that demonstrates the difference between his and President Nixon’s attitudes here!

Secretary of State

“Mr. Clean” Becomes Secretary of State

“Mr. Clean” was one of Edmund Muskie’s more enduring nicknames, earned for his decades of work on environmental legislation. As a new senator, Muskie was assigned to the relatively undesirable Public Works Committee—allegedly for offending then-Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson. Four years later, Muskie was named the first chair of the Subcommittee on Air and Water Pollution, having already become a leader on environmental issues. Muskie continued his chairmanship of the Air and Water Pollution Subcommittee for nearly two decades, shepherding the passage of numerous pieces legislation, including the landmark Clean Air Act of 1970 and Clean Water Act of 1972. After leaving the senate, Muskie continued his involvement in national environmental policy through groups such as the Environmental Law Institute. In Muskie’s view, clean air and water were an integral part of the Democratic Party ideals he believed in. In a speech titled “A Whole Society”, which he gave at the first Earth Day in 1970, Muskie declared: …If we can use our awareness that the total environment determines the quality of life, we can make those decisions which can save our nation from becoming a class-ridden and strife-torn wasteland. …We cannot afford to correct our history of abusing nature and neglect the continuing abuse of our fellow-man. We should have learned by now that a whole nation must be a nation at peace with itself. We should have learned by now that we can have that peace only by assuring that all Americans have equal access to a healthy total environment. …That can mean nothing less than equal access to good schools, to meaningful job opportunities, to adequate health services, and to decent and attractive housing.

U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance resigned in April 1980 following a failed attempt to rescue 52 American hostages in Iran. With less than nine months left in his current term but running for reelection, President Carter asked Edmund Muskie, whom he had considered but passed over for the position of vice president, to lead the State Department through this difficult period. Thus, Muskie resigned his Senate seat after 21 years in office to serve on President Carter’s cabinet. Nine months later, for the first time since 1954, he was no longer an elected or appointed government official. Rather than retiring, however, Muskie accepted a partnership in the Washington, D.C. lawfirm Chadbourne & Parke, and took on leadership roles in numerous governmental and non-governmental organizations, including the Center for National Policy, Maine Commission on Legal Needs, American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on World Order under Law, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Most notable among Muskie’s post–secretary of state activities were his work on the Tower Commission, which was appointed by President Reagan to investigate the Iran-Contra affair, and his leadership of the Nestle Infant Formula Audit Commission, which investigated allegations of unethical marketing practices in developing nations. Edmund Muskie died in 1996, and was interred in Arlington National Cemetery.

U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance resigned in April 1980 following a failed attempt to rescue 52 American hostages in Iran. With less than nine months left in his current term but running for reelection, President Carter asked Edmund Muskie, whom he had considered but passed over for the position of vice president, to lead the State Department through this difficult period. Thus, Muskie resigned his Senate seat after 21 years in office to serve on President Carter’s cabinet. Nine months later, for the first time since 1954, he was no longer an elected or appointed government official. Rather than retiring, however, Muskie accepted a partnership in the Washington, D.C. lawfirm Chadbourne & Parke, and took on leadership roles in numerous governmental and non-governmental organizations, including the Center for National Policy, Maine Commission on Legal Needs, American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on World Order under Law, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Most notable among Muskie’s post–secretary of state activities were his work on the Tower Commission, which was appointed by President Reagan to investigate the Iran-Contra affair, and his leadership of the Nestle Infant Formula Audit Commission, which investigated allegations of unethical marketing practices in developing nations. Edmund Muskie died in 1996, and was interred in Arlington National Cemetery.

See a video of Muskie speaking about the Iran-Contra affair here.

In this recording taken during a 1990 interview, Muskie recalled his negotiations a decade earlier as U. S. Secretary of State to free the U. S. hostages in Iran.

The Faceless Bastards, or “F.B.’s” for short, is how members of Edmund Muskie’s staff sometimes referred to themselves. The name referred to a story—perhaps apocryphal—from the 1968 presidential campaign trail, in which Muskie is said to have demanded during one particularly long motorcade, “Who are the faceless bastards that are responsible for this schedule?” This caricature drawn by reknowned cartoonist Pat Oliphant was given to Muskie by the F.B.’s in celebration of his 80th birthday in 1994. It stands as a testament to the love and devotion that many of Muskie’s staff members continued to feel for him long after his years in government service were over.