Stages of Shea

Actor John Shea ’70 has just been reminded of an earlier profile in Bates Magazine, in 1984, when he said that surprise rules an actor’s life.

Then and now, that’s how he likes it.

“Fate puts clues in your path that tell you that you should be doing something,” Shea says.

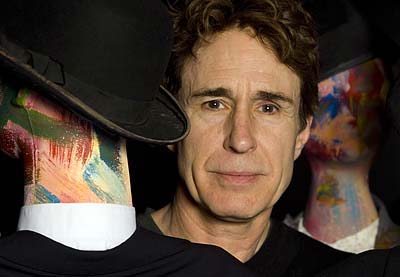

John Shea ’70 stands among costume forms for The Secret of Mme. Bonnard’s Bath in February 2007. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen.

Such as chance encounters with artists who paint images of women in bathtubs. Once, at a Nantucket art gallery, such an image so impressed Shea that he bought it on the spot. The somnolent woman in that oil painting, he says, “had a mysterious power that I really was drawn to.”

A few years after meeting the artist at that opening, Shea married her. Now he and Melissa MacLeod have two children and a home in Westchester, N.Y. (Shea has a third child from a previous marriage.) “That painting was a pinnacle of my life,” says Shea.

So naturally he seized the opportunity to play on stage a real-life painter who made hundreds of images of his wife in the bath. In the historical French artist Pierre Bonnard, playwright Israel Horovitz found plenty of meat for a feast of ideas about art, love, and mortality that became The Secret of Mme. Bonnard’s Bath. Shea portrayed Bonnard in the play’s New York debut, which ran last February.

This was a return to roots. It was on the New York stage in the mid-1970s that Shea first found acclaim. His Broadway debut, as Avigdor in Yentl, netted him the Theatre World Award for Most Promising Actor in 1976. His off-Broadway turn as a sleazy rock producer in American Days led film director Costa-Gavras to cast him alongside Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek in Missing.

There, Shea’s portrayal of the doomed, idealistic Charlie Horman was pivotal for the 1982 film. His screen time is brief, and yet his character dominates the story “because of a certain innocent, ferocious charm that seems to be a natural part of his persona,” says Timothy Lea ’83, a screenwriter and TV producer whose credits include the popular series CSI: NY.

The role was pivotal, too, for Shea. While Missing went on to win three Academy Awards, Shea went on to a career enviably balanced between aesthetic success and commercial reward, between pop culture sizzle and professional credibility.

He’s credited with more than 60 film and TV roles, including his 2001–04 stint as Adam Kane on TV’s sci-fi drama Mutant X. He has done big Hollywood pictures, small art films, starred or had recurring roles in three TV series, and played characters ranging from romantic leads to psycho killers, from Bobby Kennedy to Superman’s nemesis Lex Luthor.

Shea also directed, co-wrote, and acted in the 1998 crime drama Southie. Now he’s writing a murder mystery and seeking backing so he can direct The Junkie Priest, his finished script based on the late Daniel Egan, a Franciscan friar known for rehabilitating drug addicts and prostitutes in New York.

Shea (center) plays Paul Bratter in the Robinson Players’ fall 1968 production of Barefoot in the Park, with Bonnie Brian ’69 (left, as Corrie Bratter) and Sanford Emerson ’69 (right, as the repairman). Photograph courtesy of Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library.

But it was on the New York stage where Shea found fame, and it’s next to a New York stage where Bates finds Shea in early 2007. One afternoon prior to a performance of Mme. Bonnard’s Bath, the actor is being interviewed in a front-row seat at the play’s venue, the Kirk Theatre, in the Theatre Row complex on 42nd Street.

Shea has penetrating dark eyes, dark wiry hair, and is dressed all in black. The effect is not exactly brooding intensity — he’s warm, courteous, and generous with his answers — yet he nevertheless gives the paradoxical impression of keeping a few aces in reserve.

The stage remains his favorite venue, the wellspring of his craft. He relishes the latitude that theater affords for developing a character over time. And a key distinction from film and TV is that on stage, the director’s control ceases when the curtain goes up.

“Once we open a play, it’s ours. Nobody can stop us,” Shea says. “That’s both liberating and sort of terrifying. You’re out there on a tightrope and you have to be so concentrated to keep the play focused and alive.”

And so, a few hours after the interview, Shea is back on the tightrope. His Bonnard reads impassioned poetry to the women he wants, declares Big Thoughts, jumps up on furniture — and yet, there’s that reserve again. It’s a thoughtfulness, an inwardness that anchors Shea’s considerable stagecraft. Playwright Horovitz doesn’t spare the bombast, but Shea’s words always seem to come from someplace real.

“That quality allows the audience to project themselves onto the character,” suggests Ginny Addison Siegler ’84, who has worked as a casting director and consultant. “When he’s seemingly withholding, you see there is something going on, and you want to know what it is.”

Shea himself explains that as a mature actor, “I always look for something in a character that I can bring to help tell the truth about him. But I also look for something the character will bring to me and teach me about life.”

Yet when he started acting, as a shy teenager, the appeal was about sheer survival. “I got to be somebody else,” he says. “And I found that that liberated me.”

And yes, this was at Bates. Drafted to make a beer run one day in 1968, he found he had forgotten his backpack, with his very excellent fake ID in it, in Little Theatre after debate practice.

Returning to the theater, Shea happened into the first reading for the spring production of Much Ado About Nothing, where theater professor Lavinia Schaeffer promptly dragooned him into playing the lead role of Benedick. For Shea, it was much ado about something. “I discovered acting is really what I was born to do,” he says.

In short, another one of those portentous coincidences. “The best things that have happened in my life, happened by surprise,” Shea says. “When I think about that, there’s a miraculous quality to it.”