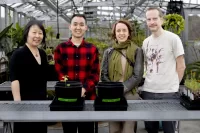

This photograph from the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library shows Fred A. Knapp, Class of 1896, and Emily B. Cornish, Class of 1895, in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, staged at Bates in November 1893.

Knapp and Cornish played the separated twins, Sebastian and Viola, in Shakespeare’s gender-bending comedy.

Fall 1893 saw another, less light-hearted gendered story play out at Bates. For the first time since the school’s founding in 1855, the “young ladies of the freshman class at Bates outnumber the young men,” The Bates Student reported grumpily.

And the men were not happy. “Should this continue until the feminine gender prevails the consequences would not be pleasant to dwell upon,” the Student reported.

The Student‘s consternation reflected the era, late in the Gilded Age, and a heightened notion of manliness and masculinity was in play in American society.

At many colleges, the new sport of football, established at Bates that very year of 1893, was praised as the masculine sport. Football demanded “coolness and nerve…courage,” the Student wrote. If played in a “manly” way — without the “slugging” that marred the game — football could develop “more self-confidence and manliness” than even baseball or tennis, then the popular fall sports.

(On a national scale, this notion of manliness was also about “promoting a sense of America’s growing white imperial power — think of Teddy Roosevelt charging up San Juan Hill,” says Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies Rebecca Herzig.)

Responding to the Student’s comments about female enrollment was a blistering letter from William Bertram Skelton, Class of 1892, who would become a Lewiston mayor and lawyer. Fear was motivating these critics, he charged — fear that women were making Bates a more academically rigorous place.

He put the male critics into two groups. One included students “who do not succeed in causing their light to shine with quite as much dazzling splendor as they anticipated.”

The second group were playboys and heathens who “have a little money and who go to college largely…to free themselves of all civilized restraints, let their hair grow long, befog their brains, stew their stomachs, and blast their reputations with dissipation, and reform afterward.”

Get over it, Skelton said. Instead, work to build up the college. “Help to put some hustle into the thing,” he wrote.

The woman in this photo, Emily Cornish, certainly hustled, and her life told another gendered story of that era. She studied at Emerson College, earned a master’s from Bates in 1899, and later taught at colleges and schools — until 1911, when she left teaching to marry botanist Walter W. Bonns.

Fred Knapp, meanwhile, became a Bates professor of Latin, retiring in 1943.