Ready to respond, 501 new students hear the call as Bates begins 145th year

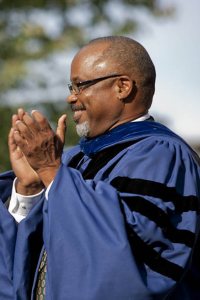

“What we do today is symbolic of what we do all year long,” Professor of Religious Studies Marcus Bruce ’77 told some 501 new students during Bates College’s Convocation on Sept. 7.

One of five speakers at the ceremony on the Historic Quad, Bruce’s keynote address eloquently wove together an explication of the College’s new mission statement with the meaning of “convocation” itself — and, most importantly, what it all means to the new arrivals.

Including the new first-year and transfer students, staff, friends and faculty, a thousand or so people gathered under sunny skies for the event. In addition to Bruce, speakers were

- Allison Mandra ’12, president of the Bates College Student Government;

- Jill Reich, dean of the faculty and vice president for academic affairs;

- Bates President Elaine Tuttle Hansen. Borrowing its title, How We Decide, from the Class of 2014’s summer reading assignment, Hansen’s Convocation charge related the liberal arts education to revelations in Jonah Lehrer’s book about the mental processes involved in decision-making;

- and the Rev. William Blaine-Wallace, whose benediction closed the ceremony.

Following the ceremonial procession of faculty and first-year students from Alumni Walk to the ranks of folding chairs at Coram Library, Mandra and Reich offered brief remarks.

See a slide show about the new-student orientation and the Annual Entering Student Outdoor program.

In a Bates video, faculty discuss the courses they’re most excited about teaching this semester.

In her welcome to the Class of 2014, Mandra noted the class’s passage from an orientation where older students guide the newbies through a bustle of fun activities, to the everyday world of Bates in session. “Camp Bates is ending, but life at Bates is about to begin,” she said. “So make the most out of it, and enjoy.”

Anticipating Hansen’s address, Reich introduced the theme of decision-making. They have choices about their learning, about how to spend their time, about who they are and the people they wish to be, she told her listeners. And every choice comes accompanied with certain responsibilities, including the responsibility of truth to self.

“This is a life that — if you choose — will prepare you to engage in the intellectual, artistic, economic, scientific, ethical and social challenges of the global community in which we live, and which you will serve as our leaders,” Reich said.

Following Bates tradition, the departing Class of 2010 last spring selected a favorite member of the faculty, Marcus Bruce, to offer the Convocation keynote. Titled A Shared Vocation, his address revealed how both the new mission statement, which Bates adopted last spring, and the concept of convocation itself actually mean the same thing: a communal call to action.

“At this very moment, we are convocating — not to be confused with cavorting — although we do that here, too,” Bruce teased the students.

He talked about his practice of bringing students to services at a historic African American church in Portland, describing the intense revelatory power of the call-and-response tradition that puts the worshiper at the center of the experience. Some students get right into it, he said, while others feel intimidated by the experience.

“I’m sure that some of you feel a certain amount of trepidation as you participate in this institution’s version of a communal call-and-response. And make no mistake about it: You are being called to something … that demands a response from you.”

A member of the committee that crafted the mission statement, Bruce focused on two phrases in the 77-word text. The wording “emancipating potential of the liberal arts,” he explained, honors and adapts wording from Benjamin Mays ’20, longtime president of Morehouse College and a mentor to Martin Luther King Jr.

Mays wrote in his autobiography that Bates “did not ’emancipate’ me; it did the far greater service of making it possible for me to emancipate myself.” For Mays, said Bruce, “a Bates education was a calling” that required a response. Bates provided a context where “a young man of African descent could lay to rest notions of his alleged cultural and/or intellectual inferiority.”

For his present listeners, Bruce went on, “your liberation may come in the discovery of ideas and ideals that will lead you to a more profound understanding of yourself and others.” On the other hand, it could manifest itself as a liberation “from beliefs and ideas that have limited your potential for growth.”

In the mission statement’s phrase “the transformative power of our differences,” Bruce tied the provocative, enlightening power of diversity to the kind of personal growth that Bates seeks to nurture not just in students, but in all who pass through. “We cannot, in the end, do this alone.”

We are here “to be transformed,” he said. “You cannot be here and remain unchanged by what you see and experience among this extraordinary gathering of people, in this place which is specifically designed to cultivate our humanity.”

“We are calling you, we are inviting you, to respond to the vocation within you, to be transformed, and to transform us by your presence and your work here.”

Bates selected the first-year students’ summer reading to give them a head start on the lifelong process of making, as Associate Dean of Students Holly Gurney explained to President Hansen, “the best decision possible for a particular situation and day — or night.” Hansen’s Convocation charge demonstrated how ideas in Lehrer’s How We Decide align with principles of the liberal arts education.

Lehrer states that the best decisions, contrary to the stereotype, combine both reasoned and emotional responses. Hansen drew a parallel with the liberal arts curriculum, which balances “hard science” with more subjective disciplines such as the arts.

The ability to organize one’s thoughts and to focus is another ingredient in sound decision-making. Hansen explained how the Bates curriculum is structured to progressively focus a student’s work, from the breadth of the general education requirements, to the coursework that constitute a major, to the senior thesis that explores a closely refined question in depth.

Similarly, with an aversion to risk being an impediment to good decision-making, she cited the pass/fail grading option as an example of ways that Bates encourages students to take risks and make mistakes that serve as lessons.

Finally, Hansen discussed the complex relationship between ethical decisions, the consideration of others in the process, and the importance of debate and dissonance in learning.

“We can get really stuck in our preconceptions,” she said. “The allure of certainty and confidence prompts us to trick ourselves into being sure” of a decision that may not be right. But the liberal arts model of education is designed specifically to counteract this kind of stuck thinking by emphasizing collaboration, a diversity of views and experiences, and vigorous debate.

Harking back to Bruce’s topic with an allusion to the new mission statement, she said that Bates is a “collaborative college, and we engage in the transformative power of our differences.”

While Blaine-Wallace tapped poetry and the fiction of Elizabeth Strout ’77 for his benediction, the most striking point came with what he called a “factual story”: the reality that Bates, “one of the finest, most expensive liberal arts colleges, is just a few blocks from one of the poorest neighborhoods in Maine.”

Lewiston is “a microcosm of the world the way it really is,” he said. “We will encourage and equip you to walk down the hill.”