‘Plucked’: Race, gender, science, medicine converge in history of hair removal

Rebecca Herzig is the author of Plucked: A History of Hair Removal in America and is the Christian A. Johnson Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies at Bates.

According to some estimates, virtually all American women have tried facial and bodily hair removal. Most remove some hair regularly, if not daily. And for the majority of men, despite the fad for the full “lumbersexual” beard, a clean shave is still the look.

If hair removal is common, though, that doesn’t make it trivial. Ever since Europeans arrived on these shores, what Americans have done with their hair has signaled racial and social status, political and cultural orientation, and even our views on freedom — all the while giving medicine, science and industry lucrative new markets.

Plucked: A History of Hair Removal, a new social history from New York University Press, weaves together for the first time Americans’ shifting beliefs about facial and body hair with the technology and business of body modification.

“You might be surprised what the history of hair removal can tell us,” says Plucked author Rebecca M. Herzig, professor of women and gender studies at Bates. “I know I was surprised when I learned that millions of Americans once used X-rays to get rid of unwanted facial hair.

“You might be surprised what the history of hair removal can tell us,” says Plucked author Rebecca M. Herzig, professor of women and gender studies at Bates. “I know I was surprised when I learned that millions of Americans once used X-rays to get rid of unwanted facial hair.

“I was more surprised to discover that, even when X-ray hair removal was banned because the radiation was so harmful, many women continued to seek it out because the stigma of facial hair seemed worse than the threat of cancer.”

Those are among the discoveries that led Herzig, a historian of science, to write Plucked. The book describes some of the dozens of methods Americans have used to try to remove body hair, from razors to harsh chemicals to lasers and even to genetic engineering.

Herzig also explores society’s evolving views of “normal” hair growth and what deviations from the norm might signify.

Until the mid-19th century, Americans of European descent looked askance at the meticulous hair removal practices of Native Americans. Yet in subsequent decades, hairiness — especially on women’s faces — was variously interpreted as a sign of racial inferiority, criminality, sexual perversion or political radicalism. Feminists in the 1960s and ’70s challenged some of those associations, transforming body hair into a symbol of self-determination.

“I use the history of hair removal to explore Americans’ changing ideas about what’s necessary, what’s natural and what’s good,” Herzig says.

Driving Plucked is its depiction of the elaborate dance between, on the one hand, those changing ideas, and on the other, the changing scientific and industrial practices that both accommodate and shape cultural perspectives.

For example, Herzig details how a clean shave became a norm for men only after World War I. During that conflict, a smooth skin was deemed necessary to ensure a properly fitting gas mask, and razor manufacturer Gillette laid the groundwork for a postwar market by supplying the U.S. military with safety razors.

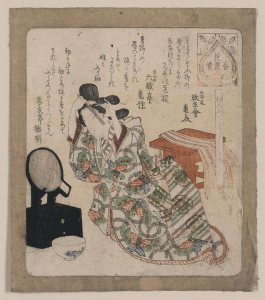

Titled “Genpuku yoshi” (“It’s good to become an adult”), this 19th-century woodcut print by Hokkei Totoya shows a woman on a lucky day for shaving her eyebrows. (Library of Congress)

As Herzig points out, “individual choice” in the realm of personal body care is a fallacy. “When we talk about ‘freedom’ in the U.S. and other advanced industrial societies, we often assume that the choices we make about our bodies are only about our bodies. But they never are, and never have been.

“Big forces are at work here. The wax that has made ‘Brazilian’ a household word is a byproduct of global petroleum production. All the depilatories we manufacture and consume end up in our waterways and landfills,” she says.

“Our choosing selves are never free of larger social and ecological entanglements.”

Herzig’s previous books include Suffering for Science: Reason and Sacrifice in Modern America (Rutgers University Press, 2005), which explores the rise of an ethic of “self-sacrifice” in American science; and, with Evelynn M. Hammonds, The Nature of Difference: Sciences of Race in the United States from Jefferson to Genomics (MIT Press, 2009), a history of scientific studies of human variation.

Herzig is chair of the Program in Women and Gender Studies at Bates, where she has taught for more than 15 years. She has won numerous awards for her work, including the college’s Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching, and currently holds the Christian A. Johnson Chair in Interdisciplinary Studies. Read about Herzig’s lecture marking her appointment to the Johnson Chair.

The Johnson Professorship, supported by an endowment established by the Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation, recognizes a faculty member who has made transformative contributions to interdisciplinary studies.

Herzig received her doctorate in the history and social study of science and technology from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and her bachelor’s degree in American cultural and environmental studies from the University of California, Santa Cruz.