“It can be exciting, seeing the progress that smart kids can make in a short period of time,” says Robert Feintuch.

The smart kids in question are the studio art majors who show nine months’ worth of creative work in the annual Senior Thesis Exhibition at the Bates College Museum of Art (opening this year on April 6).

Since he started at Bates, in 1976, senior lecturer Feintuch has been one of two advisers to help student artists prepare for the show, working in tandem for many of those years with a colleague in the art and visual culture department, associate professor Pamela Johnson. The exhibiting artists in the Class of 2018 are the last Feintuch will advise at Bates.

Sophie Olmsted ’18 installs her work in the 2018 Senior Thesis Exhibition at the Bates Museum of Art. Senior Lecturer in Art and Visual Culture Robert Feintuch, who advises the studio art majors during the winter semester, is in the background. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Feintuch, who retires this year, is himself a highly regarded painter, represented by the Sonnabend Gallery in New York City and by the Zevitas Marcus Gallery in Los Angeles. “I see teaching thesis as an opportunity to respond to students’ individual interests, while pointing them to historical and contemporary work, as well as to larger contexts that could inform them,” he says.

But, Feintuch adds, “in the end, it helps for young artists to fall in love with something.”

Meet the artists

Who are the artists featured in the 2018 Senior Thesis Exhibition, and what’s their work about?

Those objects of love vary widely for the 14 artists in this year’s senior show — from animations made by Durotimi Akinkugbe to the kinetic grid drawings of Meghan Cleary, and from Georga Morgan-Fleming’s abstract paintings to the utilitarian pottery that Max Breschi, of Carlisle, Pa., is giving away to local residents through the exhibition.

All told, Feintuch says, “the mediums in this year’s exhibition include vessel-based ceramics; straight, digitally and hand-altered photography; drawing, hand-drawn animation, painting, and sculpture.”

The seniors’ thematic interests, he continues, “include sociopolitical concerns about gender and identity, emotional or comic responses to daily life, drawings as meditational devices, ceramics as functional and/or aesthetic objects, and sculpture as a metaphor for memory.”

With her ceramics in the foreground, Sophie Olmsted ’18 and adviser Robert Feintuch ponder the arrangement of student art in the 2018 Senior Thesis Exhibition a few days before the opening. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

He continues, “My students often start with elaborate intellectual ideas that are clearly expressed in spoken or written language. Then they make the work, and the result has very little to do with the starting point. It’s not that visual work is separate from ideas — it’s that the visual works differently from language.

“I try to encourage my students to see how the visual information they get from making can be used towards a wide range of ends.”

As exciting as the exhibition is — and as portentous as it may be for the graduates who go on to careers in art — it nevertheless bears a sting for the exhibitors. “It’s very bittersweet to finish a project that you’ve been working on for a whole year,” says ceramist Sophie Olmsted ’18 of Winchester, Mass.

“I’m proud of what I’ve done — but I also feel like it’s not done,” she says. There’s more for her to explore. She adds, “It’s also exciting to see my work compared to other people’s, and see the interactions in the gallery of our hard work together.”

2018 Senior Thesis Exhibition artists

+Durotimi Akinkugbe ’18

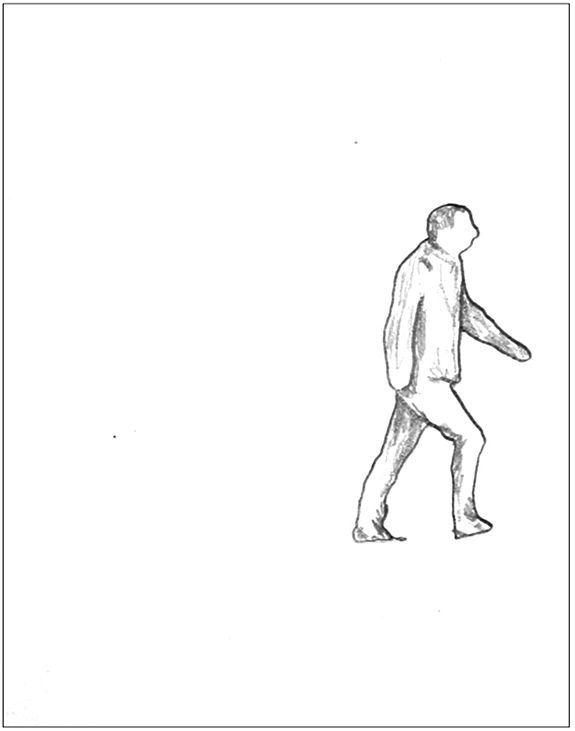

Durotimi Akinkugbe, of London, regards animation as a means of distilling and expressing his artistic ideas and his feelings. His current work uses hand-drawn imagery to probe for meaning in mundane day-to-day activities. Beginning with a concept that he wants to portray, Akinkugbe embarks on “a series of unraveling challenges – developing ideas, prototyping, and refining.” He explains, “What I like most about animation is that I get to combine different artistic skills all for the purpose of making films.” While his ultimate goal is the ability to “weave together powerful imagery,” he adds, “for the time being I feel that entertainment is a worthwhile goal to strive for.”

An untitled work by Durotimi Akinkugbe (2018), pencil on paper animation for HD video (border added).

+Saleha Belgaumi '18

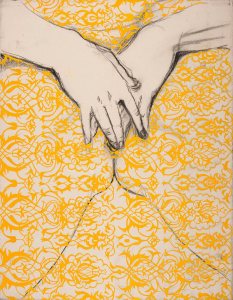

Saleha Belgaumi’s art explores her identity as an American-Pakistani woman. “I attempt to represent some of the complexities of being a biracial woman of color, of Muslim heritage, living in contemporary U.S. society,” says Belgaumi of Karachi, Pakistan. She overlays close-cropped charcoal drawings of the nude female figure with traditional Islamic tile patterns in oil paint, exploring how these elements interact on the canvas and how they “allude to different histories of representation.” While she uses her own figure as reference, “the works are not self-portraits,” Belgaumi says. “I strip the figure of its distinct individuality and ask viewers to relate viscerally to the body in front of them.”

“Dekh, Magar Pyaar Se” by Saleha Belgaumi (2018), oil and charcoal on canvas.

+Joshua Bilchik '18

Joshua Bilchik of Brookline, Mass., makes decorative pots and vases from porcelain. Influenced by ancient Greek amphorae and work from the Ottoman ceramic center of Iznik, he forms smooth, curved vessels. Yet for his surface decoration, Bilchik finds inspiration in the rectilinear, geometric, and colorful stylings of modern and contemporary painters like Piet Mondrian and Ellsworth Kelly. Bilchik exploits the tension between the pottery’s rounded forms and the hard-edged surface designs. He says, “My intention is to make work that explores contrasts within and between the physical presence of the pots and their decoration.”

+Max Breschi ’18

Max Breschi’s pottery is utilitarian art made with the desire to build community and strengthen relationships. “I imagine my ceramic vessels bringing simple pleasures to someone’s life as they drink a cup of coffee or look at a flower in a vase,” says Breschi of Carlisle, Pa. As he creates a work, he imagines the piece in the hands that will ultimately put the product to use. “To connect the communities of Bates and Lewiston and to show my appreciation to the community,” he says, “I invite community members to visit the Bates museum and to choose one of my pieces that speaks to them.” It’s a way to give back: Local residents “have played integral roles in my education and forging a new home for me throughout the years.”

Untitled glazed stoneware works made in 2018 by Max Breschi.

+Maria-Anna Chrysovergi ’18

Maria-Anna Chrysovergi of Nea Moudania, Greece, sees photography as a tool for personal empowerment and “as a mirror of my dreams and secret desires.” Her images compose an idealized story of her time at Bates, compressed into the course of a single day. Inspired by the children’s book Matilda, about an oppressed child who gets the power to move objects with her mind, Chrysovergi imbues her photographic narrative with magical elements as a way to empower her own character. “I admire Matilda’s courage, intelligence, and humor,” she says. “I hope viewers can see how our stories are connected, and that some of them see the work as an invitation to imagine how their lives would be if they had magical powers.”

An untitled inkjet print by Maria-Anna Chrysovergi (2018).

+Meghan Cleary ’18

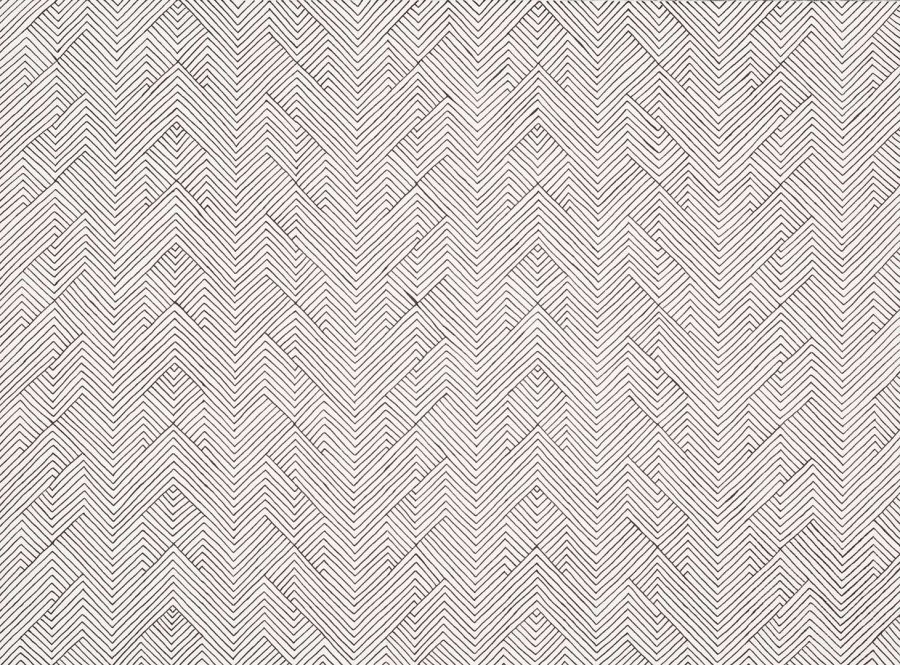

Meghan Cleary’s geometric pen-on-paper drawings explore movement. Inspired by the abstract artist Agnes Martin, Cleary of Burlington, Vt., begins each piece with a grid, choosing either to follow and accentuate the existing lines or to use them as a basis for new patterns. “I approach this work almost like a puzzle,” she explains: “It becomes my job to figure out where the pattern or design goes.” Deviation from the grid imparts more kinetic energy, she says, “which is an aspect of my drawings that I’ve been particularly interested in exploring this year.” She adds, “I don’t strive toward any particular conceptual meaning. For me, it’s simply about the marks on the page and how they interact with each other.”

“Fastest Man Alive #1” (2018), a drawing in ink and graphite on paper by Meghan Cleary.

+Nora Dahlberg ’18

Nora Dahlberg of Arlington, Va., uses prosthetic and theatrical makeup practices to transform plastic-foam wig forms “into something inhuman and creature-like.” She’s motivated in part by the desire to highlight costume and makeup techniques using clay and plaster that are highly regarded specialties. At a time when computer-generated imagery is the prevalent means of altering actors’ appearances, Dahlberg strives to “showcase prosthetic design and construction as an art form.” While CGI has its benefits, Dahlberg feels it is lacking: “People cannot experience the product face-to-face, only on a screen. I want to create tangible objects that evoke a visceral reaction from my audience.”

+Stephanie Flores ’18

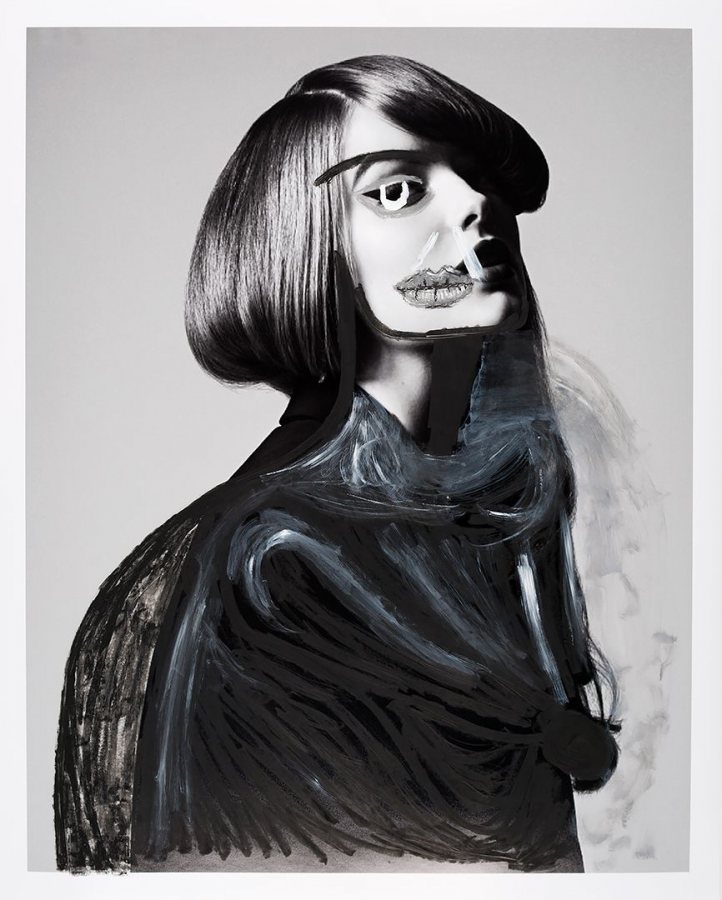

Stephanie Flores of Highland Park, Ill., views her work as an expression of her love/hate relationship with the fashion industry. “I find fashion’s ability to transport me into new worlds exciting,” she says, and she values the beauty and layered meanings of fashion apparel and photography. Yet she’s well-aware that the industry reinforces unrealistic beauty standards. “So I’ve chosen to just stay conflicted and let that dictate the direction of my artwork,” she says. Working with published fashion images to emphasize the persistence of these interpretations of beauty in her daily life, Flores alters the photographs with overlaid marks – made both consciously and subconsciously – that reflect her inner conflict and frustration with the industry.

An untitled work by Stephanie Flores (2018), in oil stick, oil pastel, and acrylic paint on InkJet paper.

+Emily Jolkovsky ’18

Emily Jolkovsky of Avon, Minn., says that she “began doing observational photography at a time when I was overwhelmed by ugly details of the larger picture.” Now she combines photography with her study of philosophy in search of insight into such abstract concepts as “good and evil, their interdependence, human nature, and language.” While she hopes her work will provide clarity, she strives, at least, to display the world’s simple and often overlooked beauty. Jolkovsky believes the world is full of answers: “I don’t want to attempt to give my own. I’d rather help provide some calm in a chaotic world by pointing out the quiet beauty that can be found in the banal.”

+Kiana Keller ’18

Kiana Keller’s pottery is loosely inspired by vessels used in Japanese tea ceremonies — “quiet and intimate, small-scale and subtle,” says Keller of Mililani, Hawaii. Yet the work expresses its own serendipitous character. “I’m interested in the tension between functionality and aesthetic choices,” she notes, as well as the organic conflict between planning a piece, on the one hand, and the “serendipity and chance inherently involved in making ceramics” on the other. Ultimately, Keller says, she celebrates the spur-of-the-moment decisions that can lead to stronger and more interesting pieces. “Sometimes, something happening in the moment takes me in a completely different direction,” she says, “and I just go with it.”

An untitled work in white stoneware with celadon glaze by Kiana Keller (2018).

+Louise Marks ’18

Louise Marks of Mount Pleasant, S.C., was inspired to create her assemblages by the sight of a burned-out house. Starting with “ash-covered wood, copper piping, wallpaper, and the occasional brick,” she fits the pieces together “as if they fell out of the sky and into these strange, but well-composed formations.” She explains, “I want the sculptures to stand in an unorthodox way, to make dramatic negative and positive spaces, to be visually interesting in the round, and to invite the audience to think about the meanings of and possible purposes” for refuse and wreckage. Originally wanting to paint portraits, Marks says that “in a surprising turn of events, I’m now using a hammer instead of a brush.”

“The Oldest,” an assemblage sculpture by Louise Marks (2018), made from electrical wire, found wood, wallpaper, brick, and nails.

+Madeline McKay ’18

Madeline McKay of Bala Cynwyd, Pa., is inspired by mapping practices to make images that explore personal and societal connection. With paint, pencil, marker, and ink, and Mylar overlays, she creates “diagrammatic representations of reality drawn from land, space, and movement through space.” McKay focuses on “mapping social, political, and environmental systems…responding to the ways in which reality feels chaotic and fractured on a societal level,” with society’s smartphone habit, and her own separation from loved ones, as contributing factors. Her art seeks to address this disorder “by reformatting, reordering, and filtering information and realities into legible, navigable systems of meaning – what, for me, feels like a necessary task.”

An untitled work by Madeline McKay (2018) in acrylic, ink, marker, and graphite on Mylar.

+Georga Morgan-Fleming ’18

Georga Morgan-Fleming of Belmont, Mass., describes her work as a “way for me to explore my experiences of people and events and the ways those things exist in my memory.” Explicitly subjective, her images explore our perception of memory as compelling truth, even as the components of memory are shifting, indistinct, and ephemeral. Painting with oil on canvas, Morgan-Fleming uses the color and quality of her lines to explore the fogginess of memory, allowing them to “waver and falter as they meander around the plane and sometimes disappear.” She says, “I want people to follow my lines and feel their way through the paintings like I have, moving tenderly, boldly, or stumbling uncertainly.”

An untitled oil painting on canvas by Georga Morgan-Fleming (2018).

+Sophie Olmsted ’18

Sophie Olmsted’s creative process evolved from making wheel-thrown pottery to hand-building vessels after she took a figurative sculpture class in Paris. Hand-building, says this resident of Winchester, Mass., “was liberating. Rather than striving to form the perfect pot on the wheel, I was free to add and take away clay where and when I saw fit.” Her subsequent adoption of a new pinching technique has imparted new energy to her interest in making functional pottery. “I now see that simplicity plays an important role in my sense of beauty,“ she says. “I hope that when people use these pots, they are reminded that what they are holding in their hands was made by another human’s imperfect, strong, and sometimes shaky fingers.”