As the Democratic National Convention ended on Aug. 29, 1968, and the presidential campaign kicked off, many believed that the Democratic ticket — Hubert Humphrey running for president and U.S. Sen. Edmund Muskie ’36 of Maine for vice president — was dead on arrival.

“We were supposed to lose,” says Don Nicoll, Muskie’s campaign manager.

But no one figured on Muskie.

Through the late summer and early fall of 1968, a span of just a few weeks, Muskie delivered a dazzling performance that nearly turned the tables on presidential frontrunner Richard Nixon, who would win the election by less than 1 percent of the popular vote.

That was the conclusion of a Nov. 29 panel discussion at Bates celebrating the 50th anniversary of Muskie’s vice presidential campaign.

In early September 1968, the Democrats were in dire straits. The first polls had Republicans Nixon and running mate Spiro Agnew leading the Democrats, 43 percent to 28 percent.

As President Lyndon Johnson’s vice president, Humphrey had inherited some of his polling problems: Johnson was so unpopular due to the Vietnam War that he’d declined to run for a second term.

Muskie ran one of the “exemplary national campaigns of modern times.”

The Democrats also were fighting a rearguard action against independent George Wallace of Alabama. Polling at 18 percent, Wallace was courting blue-collar voters with his populist and racist rhetoric.

The Democratic ticket looked doomed.

Democratic vice presidential candidate Edmund Muskie ’36 speaks to supporters in Kennedy Park in Lewiston on Nov. 3, 1968, two days before the election. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

But the Democrats closed the gap, with Muskie running one of the “exemplary national campaigns of modern times,” said Muskie scholar Joel Goldstein during the discussion at the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library.

+Panelists for the 1968 Muskie Campaign Event

Participating in the Nov. 29, 2018, panel discussion at the Muskie Archives recalling Edmund S. Muskie’s 1968 vice presidential campaign:

- Jane Fenderson Cabot was a campaign intern in 1968 and later a Muskie Senate staffer and assistant to Roslyn Carter.

- Eliot Cutler was Muskie’s assistant press secretary during the campaign before embarking on a law career. He ran for Maine governor in 2010 and 2014.

- Joel Goldstein is a scholar of the U.S. vice presidency and the Vincent C. Immel Professor of Law at Saint Louis University School of Law.

- John Martin was comptroller for the Muskie campaign and is a longtime member of the Maine Legislature.

- Charles Micoleau was a policy and campaign director for the Democratic State Committee in 1968 and is now a Maine lawyer whose practice focuses on the public sector.

- Don Nicoll managed Muskie’s 1968 campaign and had a long career as a program and policy planner.

- Harold Pachios supervised advance operations for the Muskie campaign and became a prominent Maine attorney and member of the Democratic National Committee

“He outperformed not only the other candidates for national office that year but virtually every other national candidate in my lifetime and, I suspect, in most lifetimes.”

Here are eight takeaways from the panel, which featured former Muskie staffers and confidants as well as Goldstein.

1. On the campaign trail, Muskie was more a preacher, less a debater.

Muskie is often framed as a fierce rhetorical combatant. And why not: He was a great debater at Bates and a legend in the U.S. Senate.

“The Muskie legend is that he was a great debater who had a superb legal mind. He was and he did,” said Eliot Cutler, an assistant press secretary during the campaign who was on Muskie’s Senate staff for six years. “But a political campaign is more about the pulpit than the rostrum.”

Edmund Muskie ’36 and supporters at a 1968 campaign event. The location is perhaps New York City; third from left is perhaps Shirley Chisholm, then running for her first term as a Congresswoman. (Burton Burinsky / Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Watching and hearing Muskie connect with voters in 1968 — “in Polish halls, on college campuses, with organized labor, and liberals disaffected by the Vietnam War and Lyndon Johnson — was an extraordinary experience. And that was all about his values, vision, and voice.”

In 1968, “Muskie wasn’t a dater reaching into voters’ heads, but rather a preacher touching their hearts and stoking their souls,” said Cutler. “He was the best preacher ever.”

2. He would not dog-whistle or play to fear.

In a series of events in early October, Muskie spoke to blue-collar Democrats in Chicago, Camden, N.J., Philadelphia, and Yonkers who were slipping away from the party.

Once part of the Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition, these older voters were now “tempted by the Wallace candidacy,” said Goldstein, which was “fanning resentment about racial policies” of the Johnson administration and the decisions of the Supreme Court under Earl Warren.

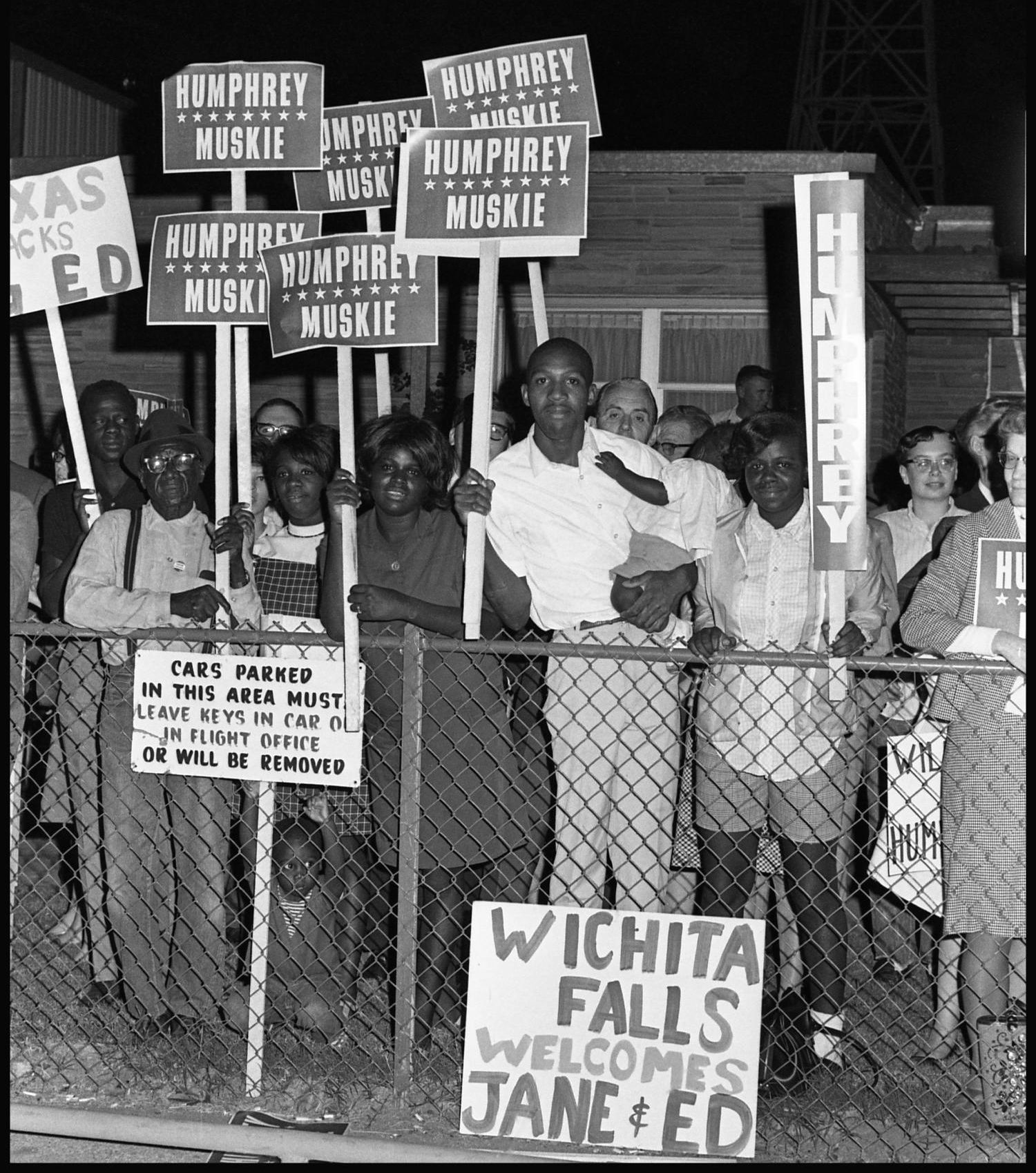

Supporters of Hubert Humphrey and Edmund Muskie ’36 greet Muskie on a campaign stop in Wichita Falls, Texas, on Oct. 29, 1968. (Jimmy Cochran / University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Midwestern State University)

Speaking to these voters, Muskie talked about his father, Stephen Marciszewski, a Polish immigrant who became a tailor in Rumford in the early 1900s.

“My father did not come here looking for fear,” Muskie would say. “He came here to escape fear and to find freedom. He did not come here looking for hatred. He came here to escape it and to find freedom.

“He did not come here seeking to deny other people opportunity. He came here to find it for himself, thinking it was available to all people who lived in America. He came here believing that freedom here was freedom for everyone.”

3. He looked and sounded the part.

Cutler called Muskie’s voice “sonorous with an extraordinary, remarkable range.”

“I see a lot of young people here today. All you know about Ed Muskie is what you’ve read in books,” said Harold Pachios, who supervised advance operations for the Muskie campaign in 1968. “You see him up there above the mantel,” pointing to Muskie’s portrait in the archives.

“He was impressive looking and highly intelligent,” said Pachios, who later became a prominent Maine lawyer. “But, oh, could he speak. Could he speak! He had the voice, a wonderful voice. He had impeccable timing, a cadence, a remarkable gift of cadence. He was rational, honest, and a solid human being.”

This is an edited version of Muskie’s powerful speech accepting the vice presidential nomination at the Democratic National Convention on Aug. 28, 1968.

Indeed, Muskie’s acceptance speech at the 1968 Democratic National Convention was a tour de force.

Making American society work, he said, “is not easy….It means learning to live with, to understand, and respect many different kinds of human beings…and accept them all as equals. It means learning to trust each other, to work with each other, to think of each other as neighbors.”

4. He had something to say.

Muskie “crept into the consciousness of the American electorate” in 1968, said Cutler.

And that was a “consequence of what I call the ‘open-mic’ character of American democracy,” he said. “If you have something to say and can connect with the American people, you can become a powerful and significant voice. And you don’t have to be loud and bombastic. Muskie demonstrated that in 1968.”

5. He bridged the gap between dissent and disloyalty.

The violence outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago left some Americans bewildered and wary of the anti-war protests, said Goldstein. Nixon and Wallace pounced, telling Americans to equate protest with disloyalty. “America: love it or leave it,” was their refrain.

Muskie, however, didn’t let the older generation off the hook. Speaking to “fat-cat groups,” the “Brie and Chablis crowd,” Muskie would say that the protesters “have honest doubts about the American system, which often closed doors to the disadvantaged.”

Indeed, “many of the inequities are your fault and mine,” Muskie said, imploring his audiences to listen seriously to the critiques and to encourage meaningful participation by the young to improve America.

He wasn’t letting the protesters off the hook, either.

This pin for the Humphrey-Muskie campaign has the phrase “Sock It To ‘Em,” probably a reference to Richard Nixon’s appearance on the TV show Laugh In, in which he delivered one of the show’s trademark lines, “Sock it to me.” (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

To audiences of mostly high school students, he would remind them that while “you are privileged to kick the government around,” with that privilege comes “the duty and responsibility of using your head, your heart, your capacity for understanding to do what is best for everyone concerned.”

So when asked by college students if he supported the emergent idea of an all-volunteer Army in lieu of the draft (which Nixon was promising), Muskie didn’t pander.

While a volunteer Army might satisfy the self-interests of privileged, mostly white college students, it wasn’t fair. Muskie supported a program of national service supported by a lottery to spread the obligation of service more equitably through society.

6. When Muskie did debate, he used his Bates education.

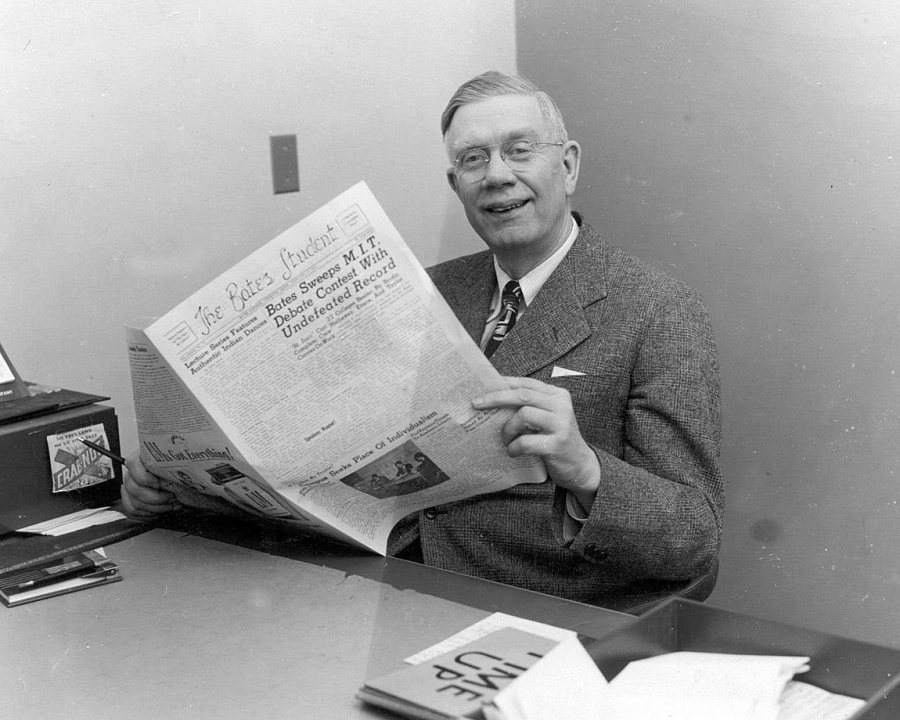

Muskie learned to debate from Brooks Quimby, Class of 1918. The namesake of the Quimby Debate Council, Quimby was a speech and rhetoric professor from 1927 to 1967.

Quimby taught his debaters to persuade an audience, not to defeat an opponent.

Rhetoric and speech professor Brooks Quimby, Class of 1918, reads The Bates Student in February 1955. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

“Persuasion: This was the key to Ed Muskie,” said Nicoll, the ’68 campaign manager. “A political campaign isn’t about beating an opponent. It’s about persuasion. That was the way he operated, and he learned it right here under Brooks Quimby.”

Persuasion means putting the audience first. Under Quimby, Bates took a “leading roll in the effort to…diminish the perception of intercollegiate debate where ‘winning is everything and the audience is nothing,’” wrote Robert Branham in Stanton’s Elm, a history of Bates debate.

7. He was willing and able to connect with anyone willing to listen.

On Sept. 25, in Washington, Pa., Muskie famously invited a college-student heckler to join him on stage.

Like other young Democrats, the hecklers that day were angry that the party — and its candidates — weren’t aggressively opposing the Vietnam War.

As the hecklers taunted Muskie, the candidate asked them to give him a chance to tell his story. “You have a chance. We don’t,” one reportedly yelled.

As Edmund Muskie ’36 addresses the audience in Washington, Pa., college student Rick Brody (left), invited to speak by Muskie, prepares for his turn at the lectern. (Mel Chemowitz/Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Muskie told the protesters to send one of their own to the stage to state his position. The ensuing discussion — with Muskie insisting that the otherwise partisan audience respect the student, Rick Brody — was reported nationally on television and in print.

The moment was both “a campaign metaphor” and an “application of a commitment to and practice of civil discourse that defined Muskie’s public service,” said Goldstein, where “information and ideas were tools of civil discourse, and civil discourse was the indispensible instrument of democracy and constitutional government.”

As Muskie would often say, “It’s better to discuss a question without settling it than settle a question without discussing it.”

8. Muskie was allowed to be — nay, demanded to be — Muskie.

Authenticity is prized in many spheres of American culture, but rarely in political campaigns. Yet in 1968, Muskie was able to be “his own man,” recalled Jane Fenderson Cabot, a campaign intern and later a member of Muskie’s Senate staff. In fact, he demanded it. “He didn’t want to be ‘bent out of shape.’ I remember hearing that a lot.”

“He told listeners what he thought, not what they wanted to hear,” said Goldstein, the Vincent C. Immel Professor of Law at St. Louis University School of Law.

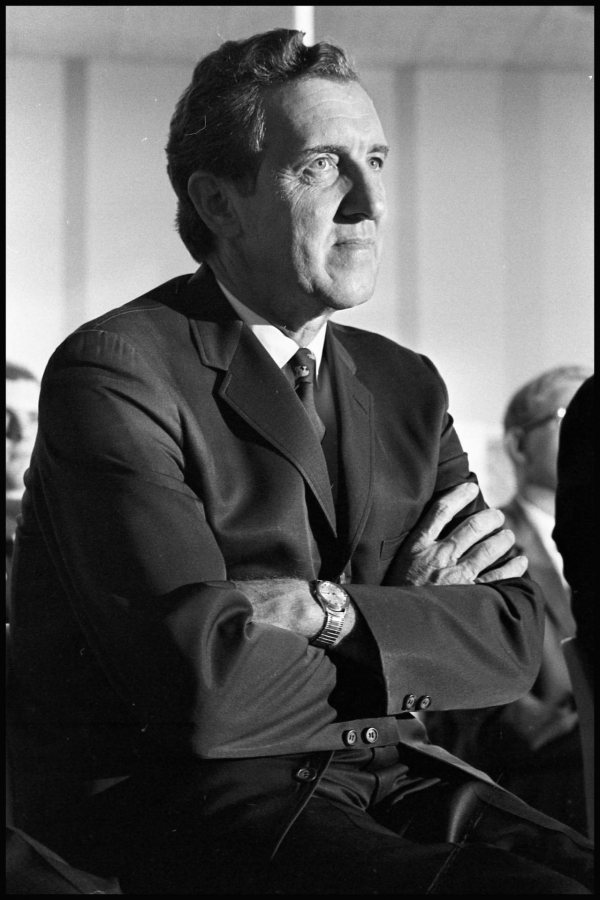

Edmund Muskie ’36 listens to a speech during a campaign visit to Wichita Falls, Texas, on Oct. 29, 1968. (Jimmy W. Cochran / University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Midwestern State University)

“He told the older generation that they’d screwed up society and should listen to their scruffy kids. He told the scruffy kids to be constructive and responsible.”

The press took notice. “Muskie is revealing himself by simply being himself — nothing more and nothing different,” wrote syndicated columnist Roscoe Drummond in October. “He doesn’t have to think of what is prudent to say…. He speaks his convictions — because he just can’t do otherwise.”