At the moment, a lot of the stained glass that distinguishes Bates’ Peter J. Gomes Chapel is staying at a house in the hills of Naples, Maine, to the north of Sebago Lake.

The house is the home and workplace of Nat Croteau, a stained-glass craftsman and the owner of Phoenix Studio. Since late last year, Croteau has been restoring the windows from the east and west walls of the chapel — the sides facing the Historic Quad and College Street, respectively.

As we reported previously, the restoration is part of a larger chapel renovation that began with a round of work early in this decade. All told, that first phase and the current phase will amount to the building’s first major refresh since it opened, in 1914.

The phase underway now also entails a lot of repair or replacement of the exterior masonry, to be performed this summer by masons from Consigli Construction, which is also overseeing the chapel project for Bates.

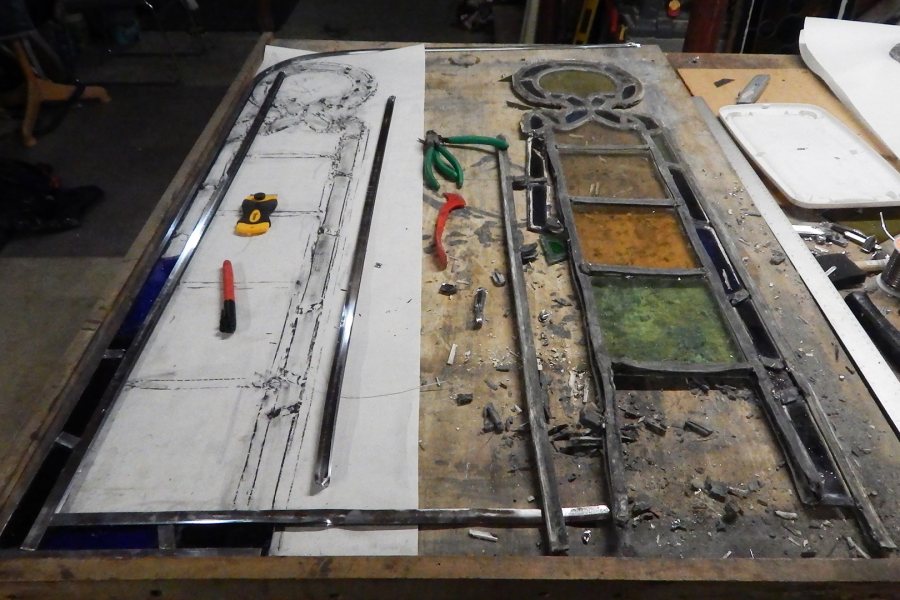

A partially dismantled stained-glass door insert at right, with materials for rebuilding it laid out at left. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Croteau is taking the windows apart, cleaning the glass and replacing damaged pieces, and rebuilding the window panels with completely new lead and glazing. The windows are scheduled to be reinstalled this summer. The stained glass on the north and south walls of the building will be redone next.

The east and west windows include eight groupings, each comprising five units, that depict persons key to the development of Western civilization (or figures regarded as such in the mid-1930s, when the glass was commissioned. Hence the absence of Elvis Presley.)

Seven of those groupings are at Phoenix. Still in place in Gomes is the eighth, depicting the poet Dante and the painter Fra Angelico, which Phoenix restored around 2012 in a pilot run for the current work.

With the mostly helpful help of the Google Maps robot, we made our way from Bates to Naples on a weekday morning. The robot guided us through long sequences of potholes and frost heaves cleverly arranged to look like roads. Phoenix is on a hillside a few twisty miles in from the lakeshore downtown.

Stained-glass maker Nat Croteau of Phoenix Studio, at left, explains a point of technique to project managers Shelby Burgau of Bates and Dylan Poulin of Consigli Construction. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Croteau welcomed Campus Construction Update and two others — Shelby Burgau, Bates project manager, and Dylan Poulin, who’s managing the chapel work for Consigli — to his basement workshop.

On the floor next to a work table was a tangle of discarded metal strips — known in the profession as “came.” These are channeled lengthwise to hold the pieces of glass, such that a cross section of came looks like a capital H. (“Came” is a so-called mass or uncountable noun, meaning that Croteau works with “came” or “pieces of came,” but not with “cames.”)

The came that Croteau had stripped off was zinc, which he suggested was used in the original window fabrication because it was more cost-effective than lead — but, he noted, zinc doesn’t have the longevity of lead, which should hold up for between 70 and 100 years. “I’m surprised the zinc lasted as long as it did,” he said.

Resting on a plastic mesh, a Gomes Chapel ventilator window soaks in a cleaning solution at Phoenix Studio. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

The bulk of the Gomes stained-glass restoration is replacing the came. Glass is brittle, but it’s stable across a span of centuries. Whether zinc or lead, came does eventually deteriorate with changes in temperature and moisture. So too does the glazing, which is the putty-like material that holds glass and lead together and seals the joint.

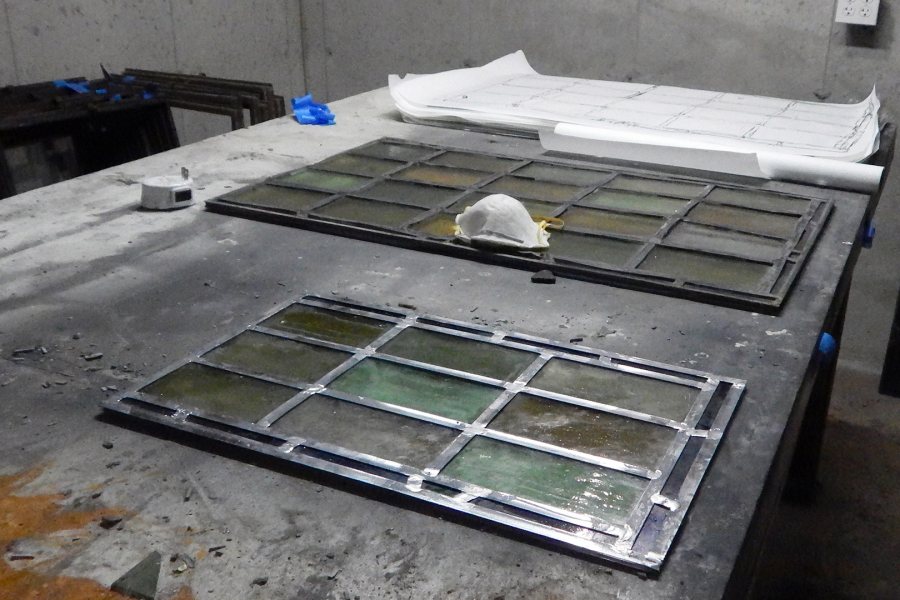

There were two panels of glass on the table. One had been reassembled with new came, the glass fitted into the channeled strips and the strips soldered together. The lead was surprisingly shiny. The other awaited new came, which was stockpiled in long boxes underneath the work surface.

Next to the table stood a stack of the large figurative windows, looking surprisingly small and dull in contrast to their radiance in the Bates chapel. Next to those were steel frames some of the ventilator windows had been mounted in.

On a second table lay two glass inserts from four of the chapel doors. Making rubbings of the design on large sheets of paper as he went along, to create patterns for reassembly, Croteau was in the process of taking the door inserts apart. A thick stack of completed rubbings sat nearby.

Two more windows were on a third table at the other end of the workroom. Actually, these were in the table: It was a shallow bath and the panels were soaking in a cleaning solution preparatory to dismantling.

Nathaniel Croteau of Phoenix Studio. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

That bath does a couple other useful things, Croteau explained. It captures dust — dust containing lead, which one doesn’t want to breathe. He recovers the lead from the cleaning solution and recycles it. (Other precautions against lead consumption in the stained glass studio include wearing masks and respirators when needed, and not eating or drinking, or licking one’s fingers, while at work.)

The soak also loosens the glazing, making it easier to take apart the panel. “Glass tends to break when it’s removed, so you don’t want something too tenacious holding it in there,” Croteau said.

Even new glazing needs to have a little give to it. When you’re putting an assembled panel back in its frame, you want the glazing to flex so that he glass doesn’t have to — glass not being very flexible. (Croteau’s own glazing is a mixture of linseed oil and powdered limestone, colored with carbon black.)

Most of Croteau’s progress to date has been on the chapel’s 32 smaller “operable” windows, meaning openable. When we visited, he had six more such windows to finish.

Why couldn’t he start the restoration with the big signature pictorial windows? At the chapel, they’re mounted into ornamental frames called tracery, and all the tracery is going to be replaced with exact replicas. The glass panels fit into gaps, so-called rabbits, in the tracery — and Croteau couldn’t rebuild those windows without knowing what thickness of came would fit the tracery.

In the foreground of this image taken at Phoenix Studio is a freshly restored ventilator window from the Gomes Chapel. The panel behind it is next up for rebuilding. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

When we visited, he had just received shop drawings that provided those dimensions. The drawings were provided by Northern Design Precast of Loudon, N.H., which will be casting the concrete tracery from three-dimensional scans taken by a Maine firm, Sebago Technics of South Portland.

Consigli has worked with Phoenix, Sebago Technics, and Northern Design on other projects. Shelby Burgau’s project management experience prior to Bates, she told us after the visit, had not covered the glass and tracery techniques that the Gomes Chapel project entails — “which is why it’s awesome to be partnered with people who are the best in the state at doing this.”

Can we talk? Campus Construction Update welcomes your questions and comments about campus improvements. Please e-mail news writer Doug Hubley, stating “Construction Update” or “Robot, didn’t I just drive through here?” in the subject line.

The window openings in the Gomes Chapel have been filled temporarily with polycarbonate panels while the stained glass is being restored. The substitute material is so clear that you can see College Street — note the streetlamp — through the building from the Historic Quad. The tunnel-like shape at right is a reflection. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)