What can we learn by interpreting new and classic works of literature through a “mad Black” lens? In literature, how are Black characters with mental illness and cognitive disabilities portrayed, particularly in Black contexts? Do these characters exist for their own ends, or to help other characters grow?

Associate Professor of English Therí Pickens, who studies Arab American and African American literature and disability issues, explores these questions in a new book, Black Madness :: Mad Blackness (Duke University Press, 2019).

Pickens describes the book as an “intervention,” meant to “bring the two fields of critical race studies and disability studies into conversation.”

“When I’m in disability studies audiences, I make sense to them, and when I’m in critical race studies audiences, I make sense to those folks as well,” she says. “The question for me became, ‘What is it that’s keeping these two from being in conversation?’”

In the book — and in this Q&A — Pickens explores how Black writers of speculative fiction (an umbrella term for science fiction, fantasy, and other genres) think about the intersection of Blackness and disability, and how their theories can inform us about a wide variety of literature and film.

Why did you decide to use Black speculative fiction to discuss madness and Blackness?

If you were to think about Black speculative fiction as a space of theory rather than just a space of enjoyment or escape, then what you have is a rich ground of theory to work with. Black speculative fiction unmoors you from time and space, allows the imagination to go places that realist fiction doesn’t.

You write that many scholars see Blackness and disability as “mutually constituted,” or dependent on one another. What do you mean by this?

Ellen Samuels is the person who gives us these ideas. Her book Fantasies of Identification talks about how race, gender, and ability are created as narratives in the 19th century. At the very beginning of the 19th century, we didn’t have the railroad. We were still in an antebellum, agrarian economy for the most part. By the end, we’re pressing against the Industrial Revolution.

People’s relationships to each other and to the world were also changing. In the U.S., with an agrarian, slave economy, you had to know who’s Black and you had to know who’s white because it’s a matter of property, a matter of freedom, a matter literally of life and death.

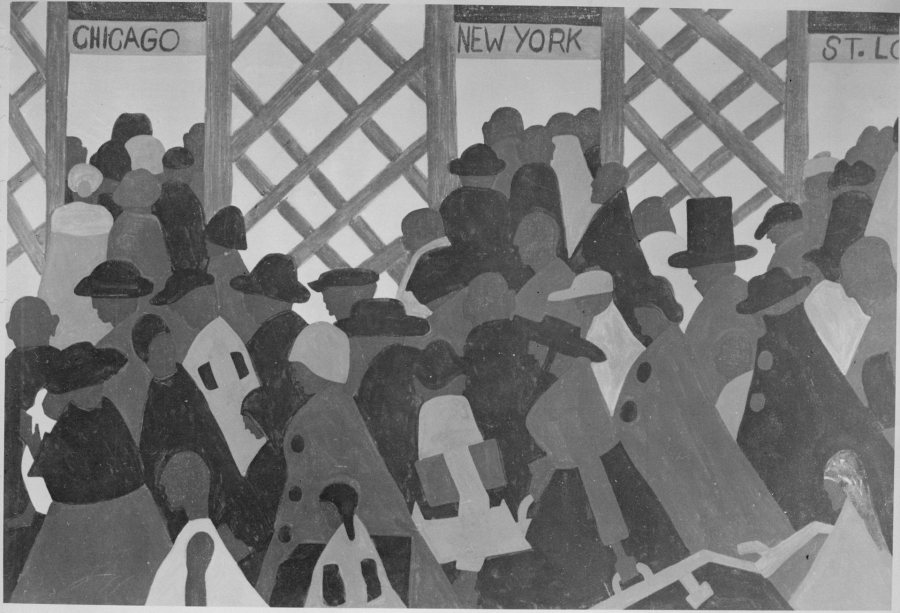

When six million African Americans migrated from the southern United States to the North in the 20th century, racial categories that existed in the antebellum South broke down. (Jacob Lawrence, Harmon Foundation Collection, Wikimedia Commons)

When you have cities and the Great Migration of African Americans that happens at the beginning of the 20th century, those categories break down. If you don’t know where someone comes from and who their family is, you don’t know for sure whether they are white, whether they are Black.

Likewise, Kim Nielsen has a book called A Disability History of the United States. She talks about how almshouses and asylums arise in the 19th century, because prior to that people were taken in by their families. There was no need for public assistance of that sort. Historically speaking, race and disability are mutually constituted, created at the same time, and reliant upon one another.

What is an example of mutual constitution?

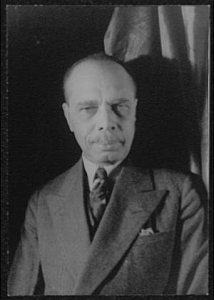

There’s a book called The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, by James Weldon Johnson. It was published as an autobiography in 1912, but it was a hoax, so it was republished as fiction in 1927.

James Weldon Johnson explored the intersections of race and ability in The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man. (Carl Van Vechten, Wikimedia Commons)

When the main character passes from Black to white as a result of having witnessed a lynching, he is refashioning himself in terms of race but also in terms of gender, because to refashion oneself from a Black man to a white man is to grab hold of certain ideas about masculinity which, by definition, include mental and physical capability.

In order to adequately take on the persona of a white man in late 19th-, early 20th-century America, what one also takes on is mental acuity. As a Black man, the main character was a very successful ragtime musician.

As a white man, he blends into a crowd. He also, in so doing, moves himself away from music, which people did not consider intellectual at the time, to banking. That narrative of passing is about gender self-fashioning, racial self-fashioning, and holding onto narratives about mental ability and mental acuity that are intertwined with them.

In the book you also push back against the idea of mutual constitution.

As we progress into the 20th and the 21st centuries, it doesn’t make sense to think about madness and Blackness in that way anymore. It is not necessarily the case that both are being created or understood with the same kind of equality or parity. There are times when madness overrides Blackness, and there are some times when Blackness overrides madness.

When you think about race and disability, you have to think about the way that white disability is constituted against Black ability, or Blackness in total. So Black disability can’t be recuperative in that context. Black disability gets mobilized as resistance but the two together don’t necessarily amount to resistance.

In Octavia Butler’s Fledgling, Shori, the protagonist, knows she’s Black and that she has amnesia, that she’s considered disabled and a “mongrel,” according to her vampire people. But knowledge about that doesn’t provide the foundation for her resistance. It is her knowledge about how the community works and her desire to finagle around that that creates the moment of resistance.

In that moment, she’s constituting herself not just as Black, and not just as disabled, and certainly not necessarily those at the same time. She’s also constituting herself from a position of antiracism and anti-ableism.

You argue for the need to look at madness in specifically Black contexts. Why is this important?

In different cultural contexts, disability acquires different meanings and makes meaning differently. There are various kinds of Black communities, but in the fictional Black community of Nalo Hopkinson’s Midnight Robber, madness and mental illness are constituted by communal assent.

People get together through their daily actions, through their gossip, through their play, through their work, and decide that the main character, Tan-Tan, is mad, disturbed in some way, an outlier.

Nalo Hopkinson’s novel Midnight Robber begins with a scene of the Caribbean New Year’s Day parade Junkanoo, shown here in Jamaica in 1975. The subsequent Carnival celebration is a motif throughout the novel. (Photo by WikiPedant at Wikimedia Commons)

There’s also a character, Quamina, who has what might be termed a cognitive disability. There’s not as much pressure on her to perform her disability in this particular Black community, the way that cognitive disability performs in other communities.

When we think about characters that are configured as autistic, in white texts they are usually exceptional, or they are annoyances, or they’re people you live with because they’re useful. We need look no further than Sherlock Holmes or Sheldon Cooper from Big Bang Theory. In those texts, those characters are exceptional, or they are a burden.

In Midnight Robber, Quamina is part of the landscape. There are some folks who have ableist understandings of her, some who want her to perform a kind of “good cripple” narrative, some who want her fixed — but the text doesn’t endorse any of those.

She’s part of the community. She contributes, she lives, she laughs. There’s a scene where she and her mother are laughing and enjoying a story with the same facial expressions. Part of what is depicted there, which isn’t often depicted for characters with cognitive disabilities, is kinship.

In discussing narratives about Black people with or without disabilities, you argue that these characters are often written “for” other characters. How does this work?

When you have Black disabled characters in texts that are beholden to an ideology of white supremacy — which includes ableism — you have characters that don’t exist by themselves. They do exist in service of others.

Downton Abbey falls into this trap. The only major character in six seasons that we see that’s Black is Rose’s love interest, Jack, who does not quite exist for his own ends. We get very little backstory about him.

All you can see is the bratty Rose instrumentalizing this young man to get back at her mother. Lady Mary, one of the main characters, says as much. Now Jack, the Black character, attempts to allay these fears for Lady Mary — “Rose is more than you think she is,” blah blah blah. We don’t believe him, because after that scene he ceases to exist.

This also happens in the first four episodes of the first season, in terms of disability. There’s all this brouhaha about how Mr. Bates, the valet to Lord Grantham, uses a cane and has a limp, and the servants have to pick up the slack.

The entire storyline is about Mr. Bates having a stiff upper lip and how he’s going to leave because he knows what’s best for the estate. Disability is a moment for Lord Grantham to insert himself as liberal and ultimately insist that he stay.

For the Jack narrative and the Mr. Bates narrative, what you get is never a dismantling of ableism or racism. What you get is, “This is the way the world is, and there are some good white people who are able-bodied.”

The characters’ difference is only instrumentalized for the announcement of the good of the other characters, without ever attempting to dismantle the narrative itself or even expose it as wrong. The stories never say, “This is insidious.”

You make the case that incorporating race and disability into literary criticism requires a new conception of the novel itself. What is a “mad Black text,” and what does it mean to interpret a novel, film, or other text through a mad Black lens?

Mad Black texts, as an aesthetic, privilege time as nonlinear and the sonics of the texts. Midnight Robber is really a character telling you a story — that’s the way it’s set up. Fledgling has quite a bit of aural storytelling in it.

Many of Toni Morrison’s texts do not adhere to linear time and often have something in them that forces you to think about the sonics of language. The end of Beloved, “This is not a story to pass on,” has multiple meanings because of the sonics of the past and the inflections of it.

Toni Morrison, pictured here with President Barack Obama when she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012, made use of the sonic in her novels. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

When you choose to interpret something as mad and as valid as such, and as Black and as valid as such, you change the interpretation of the novel. In Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, for instance, if you look at the woman in the attic, you get an entirely different interpretation.

When Chinua Achebe looks at Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, he gets a very different picture. If you’re watching Downton Abbey, and you look at the camera angles and the storylines of characters with disabilities, it changes the narrative locus of the series.

As an English professor and literary critic, what is it like to read books that you enjoy, but with a critical eye?

As a scholar of English you don’t necessarily come to books for pleasure. They’re usually recommended to you by someone in the field, by a relative who knows you work on this, by some well-meaning stranger. You end up with certain books. When you like them, it’s better.

I think every reader is a critical reader; some have more tools in their toolbox than others. One of the things that I like about the classroom is that when you’re reading something that’s been assigned, or you’re reading something someone gifted you, you not only have the tools in your toolbox to read it, but you have a community of readers.

There’s something about discussing a book in that community that is part of the joy of the book.