It was the Tuesday after Commencement, and Jane Costlow paced around her Hedge Hall office, up to her elbows in books, boxes, papers, and assorted memorabilia. The college’s Clark A. Griffith Professor of Environmental Studies was nearing the end of her 34-year Bates career, and the only thing left was to pack up and move out.

The scene is repeated each year, of course, but more often recently with the retirement of the baby boom generation of faculty members.

Costlow tosses some papers into a recycling bin outside of her Hedge Hall office. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

I’d seen historian Michael Jones and his wife, Judy Head, empty his Pettengill Hall office. I’d listened to poet Rob Farnsworth speak of plans for his beloved books piled high in Hathorn Hall. I’d learned how historians Dennis Grafflin and John Cole went door to door on their Pettengill corridor, asking colleagues to adopt tomes they themselves couldn’t take home.

“Don’t worry,” said the student, who had picked up a book. “Your old friends will make new friends.”

And I’d heard how my husband, historian Hilmar Jensen, had regretfully placed 200 of his volumes in boxes labeled “free books” in the lobby of Perry Atrium. All were eventually claimed. Pausing one day to unload a final armful, he remarked to an observant student, “This feels like saying goodbye to old friends.”

“Don’t worry,” said the student, who had picked up a book. “Your old friends will make new friends.”

For the generation of scholars and teachers who have painstakingly collected books by the hundreds, even thousands, the task of retiring and closing up an on-campus shop presents various emotional and practical challenges, not the least of which is, “What do I do with all those books?”

Costlow pauses for a moment with a stack of books she’s packing in her office. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

That vexing question, along with other rites of passage faced by baby boomers emptying the scholarly bench, planted the original seed for my interest in documenting the last year of somebody — anybody’s — teaching at Bates.

In August 2019, Jane Costlow gamely stepped into that role. There could have been no more willing, insightful, nor patient subject.

When her classroom teaching career stopped abruptly and early, in March 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, she gracefully transitioned to remote teaching. When the semester ended (Costlow did not teach during Short Term), she spent long hours in her Hedge office, clearing the space for her replacement, a recent Ph.D. who will move in when he arrives on the Bates campus sometime this summer.

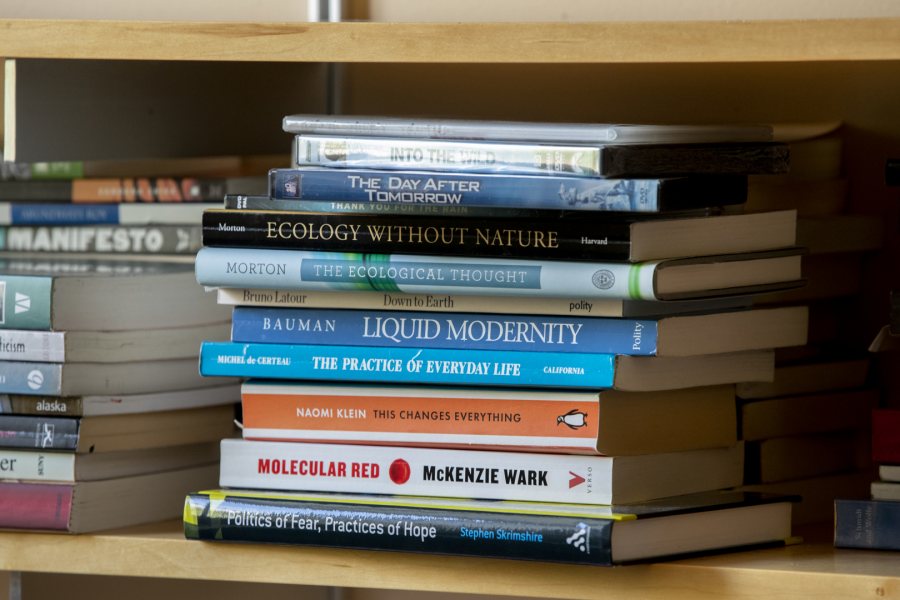

Costlow met that young scholar at a symposium last year, and she knows he will teach courses on climate change and fiction; to that end, she’s left an assortment of books and other materials that she hopes he’ll find useful, including a folder of papers about Lewiston and Auburn.

Costlow and her husband, David Das, discuss packing strategies during one of her moving sessions. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Costlow begins a yearlong sabbatical this August, after which she will officially retire in August 2021. And she leaves at a particularly difficult time as Bates — administrators, faculty, staff, and students — confront the challenges of COVID-19 and the nation’s greater-than-ever awareness of systemic racism in U.S. society. “I really feel for people,” she said, knowing that she will no longer be an active participant in the coming struggles.

The pattern of sabbaticals, she said, “provides an incredible luxury that we have as academics to take periodic time off — having a kind of Sabbath in your life. That actually gives us a little bit of practice at shifting gears, so it’s not completely unfamiliar to no longer have the demands of teaching.”

What’s different now, she said, is no longer being driven by a need to complete this project or fulfill that obligation or stand for promotion.

Costlow began her office move-out in April by first reviewing its entire contents, deciding what to save, what to dispose of, and what to try to pass on to others. Some of her discoveries — such as two folders of correspondence — delighted her.

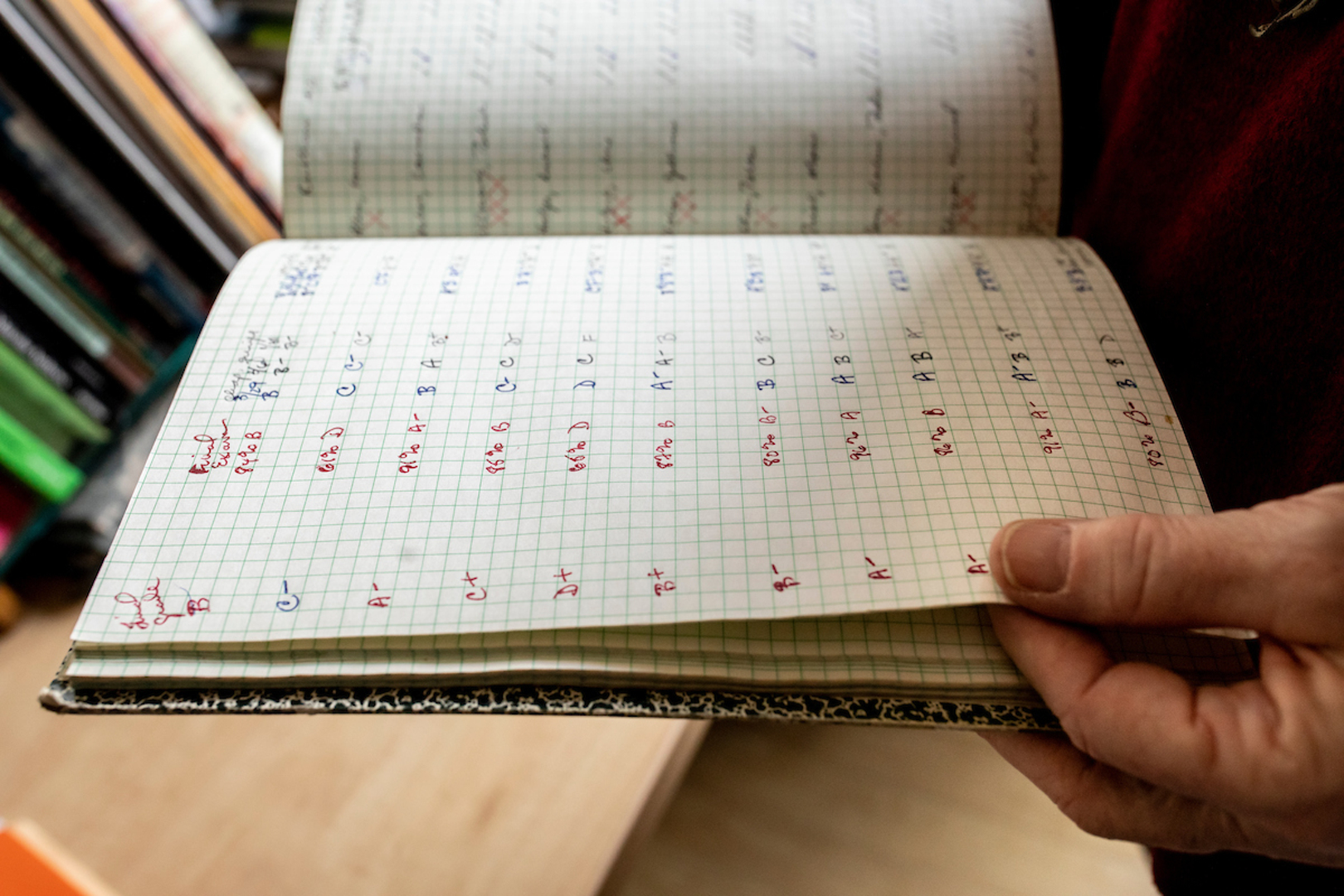

Costlow reviews the 34 years worth of accumulated files in her office filing cabinet. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“Rather than pitching those things, I actually wanted to go through them,” she said. She read the approximately 100 letters, some of which she had written, others written to her.

She found an initial note from a young female graduate student, Jehanne Gheith (now an associate professor at Duke), writing her dissertation at Stanford on the Russian writer Evgeniia Tur, one of a number of women writers from the 19th century whose work and significance for cultural history has been retrieved by scholars over the past three decades, says Costlow.

“I was the only person, certainly in English, maybe in the world at that point, who had written anything about this woman writer. So Jehanne reached out to me, and we have since become very dear friends. It was cool to find the inaugural letter of our friendship.”

In undertaking that office audit, she rediscovered a younger version of herself: a new scholar emerging from graduate school.

Other surprises included a few missives from her late colleague, French professor Dick Williamson, a “hugely important person in the early years of my life at Bates,” and a series of thank-you notes written by two other departed faculty colleagues when they were deans, Carl Benton Straub and Jim Carignan ’61, thanking her for moderating a panel or serving on a committee.

In undertaking that office audit, she rediscovered a younger version of herself: a new scholar emerging from graduate school, at Yale, “a really wonderful graduate program, but one with a very traditional curriculum and entirely male faculty, which had been pretty much my experience as an undergraduate, as well,” she said; and then arriving at Bates “interested in questions of women’s writing, feminist criticism, and different ways of thinking about cultural legacy and whose voices are heard.”

As she looked at all the books she’d acquired, all that she’d read, and what she’d written — unpublished and published — and conversations she’d had with others, she was struck by how much had changed over four decades.

In particular, she thought of the number of women who are faculty now and their positions within the academy, and the waves of various attempts to fundamentally open up and change curricula and syllabi. “I found myself looking back at the examples of how I have tried to do that, and the people that I’d worked with and leaned on.”

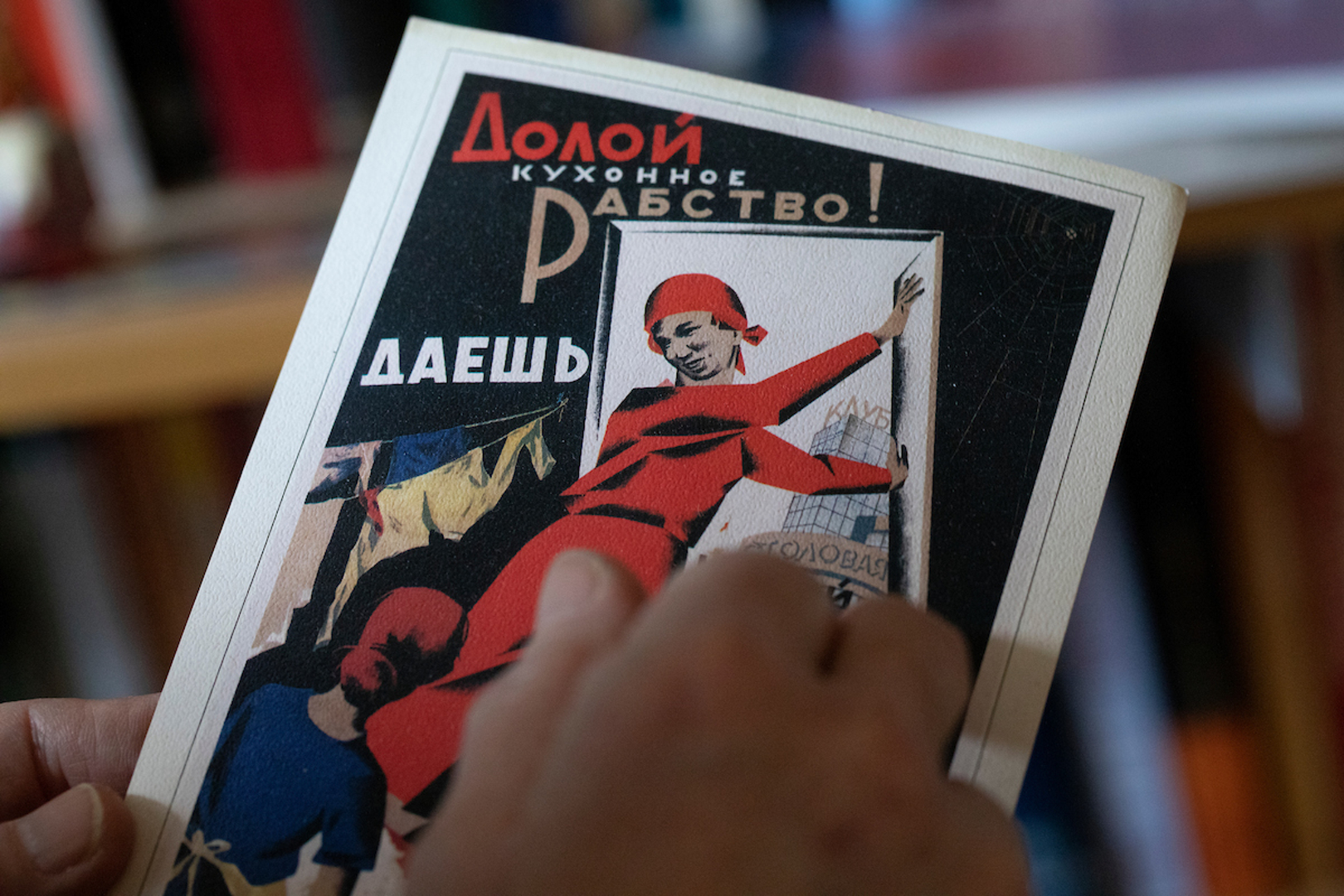

“Be gone slavery of the kitchen.” Costlow holds a reproduction of a 1931 poster by Soviet painter Grigory Mikhailovich Shegal. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

She leafed through documents from a seminar she’d participated in when Bates was developing courses for its new women’s studies program, decades ago, her mind on the past and the present.

“Right at this moment, I feel just how enormous the rock is that so many different people are trying to push up the hill of fundamental change,” she said — people “working to bring all kinds of diverse voices and perspectives into the classroom and the academy.”

“You sometimes wonder: Where is the arc of the universe heading?”

But then she has a troubling realization. “My high school experience in rural North Carolina was my most diverse educational experience as a student — everything got whiter (and much more male)” as she went on to college (Duke) and graduate school.

In high school, Costlow had African American teachers in math, and chemistry, and in homeroom. “I particularly would love to be able to find out if they’re still around, to thank them for the work that they did.”

As her mind flashes to the past and back to present, Costlow now is on the edge of tears. “It’s that moment where you’re thinking back over your career and how much has changed” — and how much hasn’t. “You sometimes wonder: Where is the arc of the universe heading?”

Jane Costlow on changes in higher education. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

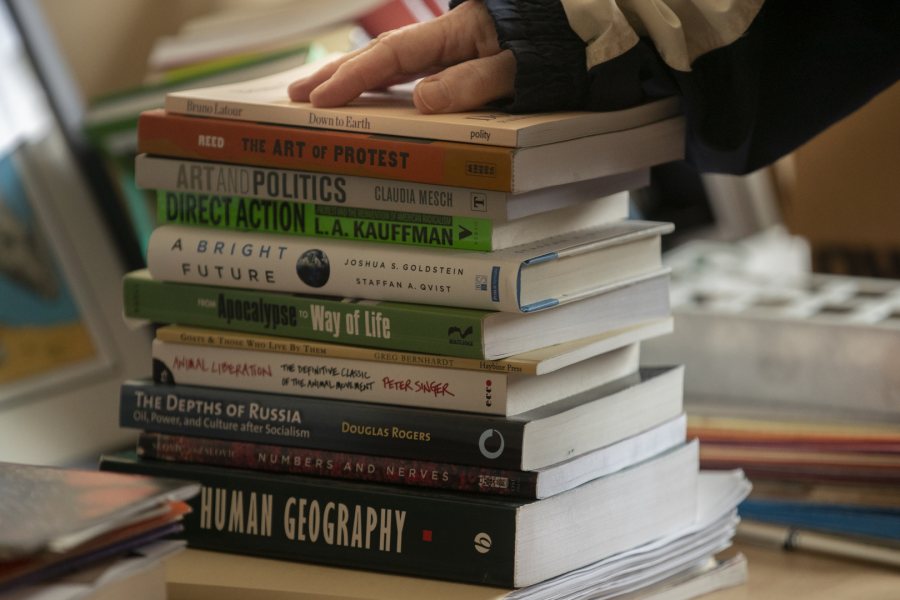

And all those books. Some she already handed off to students at the end of the fall semester or as they stopped in to say goodbye before departing suddenly in mid-March. With the help of the building’s academic administrative assistant, Jeanne Beliveau, Costlow has distributed more volumes to students. Still others will go into boxes to be picked up by students as freebies.

Costlow has also arranged to send boxes of books of American nature writing to her friends and colleagues in the English department at Turgenev State University in Orel, Russia, with whom she’s had great interactions over the course of 30 years. “Who knows what students will pick up and read in the future to get a broad sense of not just the American classics, but of diverse voices on the natural world?”

A pile of titles Costlow has selected for her successor sits on one of her office shelves. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

She mentioned a friend, Professor Emeritus of History Dennis Grafflin, who is assembling his own archive of the teaching books of Bates faculty as they retire. She gave him her copy of The Brothers Karamazov, falling apart, filled with notes and Post-its. “I think it’s a fabulous idea,” she said. “There is something really precious about all of those marks that you leave in a book.”

What will she miss most — or least — about Bates? That’s ironic, she said, since the campus has already emptied, and she’s already longing for all kinds of things: “The salad bar in the Den for those days when I don’t bring anything from home; talking to colleagues; or surprising moments with students; the energy of 20-year-olds.”

She will miss “the focused attention to writing and being able to engage with students about writing because I love thinking about what makes good writing.”

She’ll miss encounters with all sorts of colleagues, some in Ladd Library, others in Beliveau’s office in Hedge. “I’ll miss that a great deal, just being able to go down and chat with her for three minutes and maybe run into David Commiskey [professor of philosophy] or somebody else in Hedge.”

What she won’t miss: “those days when everybody is low-energy, including me, but somehow I have to crank it up to try to get the students going.” She will not miss teaching at 2:40 in the afternoon. “I always found that an impossible time to teach. I guess it’s my body rhythm.”

She will not miss grading. She will not miss having to sit down with a stack of papers and contemplate “how it’s humanly possible for me to get through these papers and help students with their writing.”

But she will miss “the focused attention to writing and being able to engage with students about writing because I love thinking about what makes good writing. I’m always happy to talk with students, and a fair amount of what we do in a class is talk about what makes this work, what makes it powerful? Or why doesn’t this communicate with us?”

Costlow shares a moment with Academic Administrative Assistant Jeanne Beliveau in Beliveau’s Hedge Hall office at the start of the fall 2019 semester. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College).

Although she’ll miss her colleagues, she will not miss their departmental meetings. “The wonderful kinds of conversations that you can have with people are the ones that are sometimes extemporaneous and unpredictable.” And faculty meetings? She views them as “a necessary evil,” although “there are times that faculty meetings are where we get to say really important things to each other — that’s at least as important now as it’s ever been.”

Nor will she miss multitasking. But there are probably ways she will continue to multitask in retirement because, after all, “it’s a constant in modern life, but it’s horrible.”

“There’s this paradox: being in a super busy job, then these moments when the beauty of the campus takes your breath away.”

Then, she’ll miss her time alone on the Bates campus, particularly those years when she worked in Hathorn Hall and would walk from Campus Avenue up the central path on the Historic Quad to her office. “How beautiful it was, these moments of quiet,” she said. “It’s the counterweight to multitasking. I love working at a place where you have to walk around to get to different places.”

It can be a healthy work environment, she said, one that allowed her time for reflection and an opportunity to admire the landscaping designed by now-retired Bill Bergevin and others. “There’s this paradox: being in a super busy job, then these moments when the beauty of the campus takes your breath away.”

And finally, she will really miss the chance to travel with students, something that she has already missed this year, as have many of her colleagues. “I’m being optimistic,” Costlow said, but she imagines she will continue to travel to Russia and other countries that she has not yet visited. “But in all likelihood, I won’t travel with students, and I’ll miss that.”

She anticipates her future with hope and pleasure, imagining it as a continuance of, not an end to, the last 35 years of her life at Bates.

She loves to read and write. She stays in touch with friends and colleagues in Russia. She maintains connections in Lewiston and Auburn “with groups of people that I love talking with.” She’s been part of a book group for 25 years that continues to meet on Zoom during COVID-19.

One thing’s for sure: “I just want to slow myself down. And the pandemic is oddly good for that.”

“I love this community. And I’ve been restrained in the extent to which I’ve had time to give to the community because of how all-consuming Bates can become. So I’m looking forward to having a little bit more time to give there, although a lot of people warn you as you approach retirement, not to get yourself committed to too many different things at the beginning. That seems like really good advice.”

Because of the coronavirus, some of the things she had imagined doing at the beginning of her sabbatical — such as taking a road trip to see family and friends in Virginia and North Carolina — are no longer possible, at least for the immediate future.

But one thing’s for sure: “I just want to slow myself down. And the pandemic is oddly good for that.” She has “deep, heavy, intense academic” projects that she’s working on, but she’ll take a break from those. “I kind of want to drift for a while, quite frankly,” she said. “Read whatever comes to mind. Go for walks. Garden.”

Her neighbor gave her some sourdough starter, so Costlow, a longtime baker, is growing her repertoire. And she’s returned to the piano, an instrument she played often while growing up. “It was symbolic,” she said, to clear the papers, library books, and COVID-19 masks from the piano to make space for the sheet music that has allowed her to get slowly back into Bach’s “Two- and Three-Part Inventions.”

Mostly, she says, to the extent that it’s currently possible, she wants to go on really long walks. She and her husband, David Das, assistant director for the Center for Global Education, do a lot of walking together. And she walks, socially distanced, with friends. But there’s something about solitary walking that she truly likes, and there are some great places, including conservation lands, in her neighborhood.

Costlow pauses to consider how to move these framed 1950 aerial photographs of Shackleford Banks from her office to home. “They’re images of a place I love – a really wild, undeveloped island you can only get to by boat. But they’re also images of islands that ‘drift’ — they get reshaped by water and storms. They remind me of climate change and sea level rise. How much longer will they be there?” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I am not going out to exercise,” she said, taking guidance from Thoreau in his essay “Walking,” in which he talked about the mindfulness that should come with a good, long walk — famously saying, “I am alarmed when it happens that I have walked a mile into the woods bodily, without getting there in spirit.”

Mind and body together on a walk — “I’ve done a little bit of that, which is really kind of wonderful,” Costlow said, describing a long exchange of looks she had with a chipmunk. “But we don’t do that when we live lives where we internalize our clocks so intensely, and you have to go on to your next meeting. One doesn’t do that. And it’s really not healthy.”

If anyone can start out on a long walk, and do it well, Jane Costlow can. Here’s to her continued good health.