Hot Quad, summer on campus: Back of our neck getting dirty and…say, what rhymes with “campus,” anyway?

Without the Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian to help with that couplet, we’ll just have to skip the tuneage and tell you, instead, about some construction projects in progress at Bates this summer.

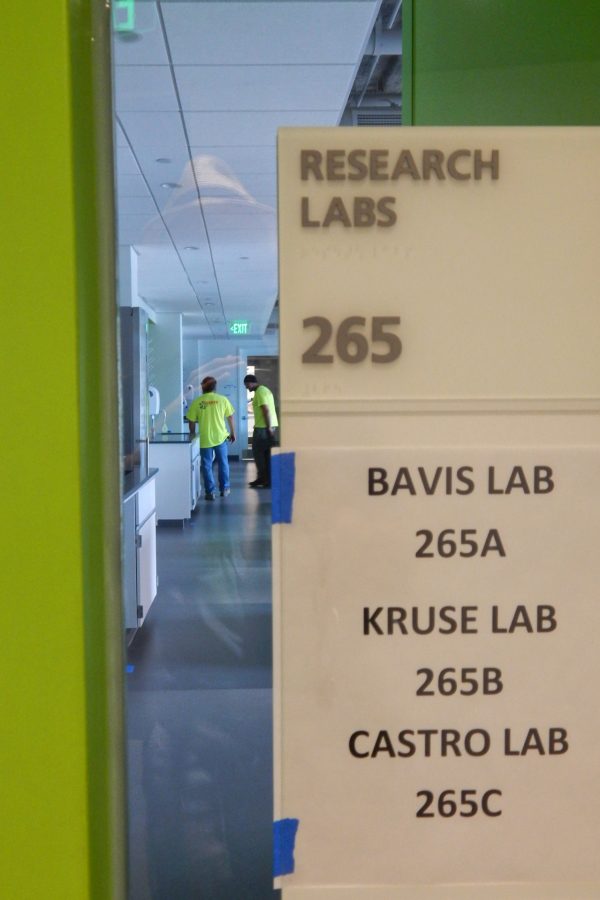

The biggest news is that faculty, their summer-research students, and staff began moving into the Bonney Science Center on June 7.

“People are in that moment of euphoria, to some degree, where they’re just so excited to finally move in after all this thinking and stressing about it,” says Chris Streifel, the Facility Services project manager for both the science center and a larger reconfiguration of science facilities at Bates. “Everybody’s just so happy to have that relief.”

Professors and staff quartered till now in Dana Chemistry Hall completed their transition to Bonney this week. Clearing Dana was the priority because that building is about to begin a comprehensive, yearlong reconfiguration into a center for teaching introductory science.

“The real story of the last few weeks has been getting Bonney done in the nick of time and getting Dana empty,” Streifel says. “That’s a pretty monumental accomplishment. And it’s something we’ve been thinking about for a long time, how we’re going to do that and setting that up” — in fact, since 2018.

Meanwhile, the faculty who’ll be crossing Campus Avenue from Bates’ third science building, Carnegie, to new digs in Bonney will start moving next week. But the bigger part of the Carnegie contingent will relocate in August.

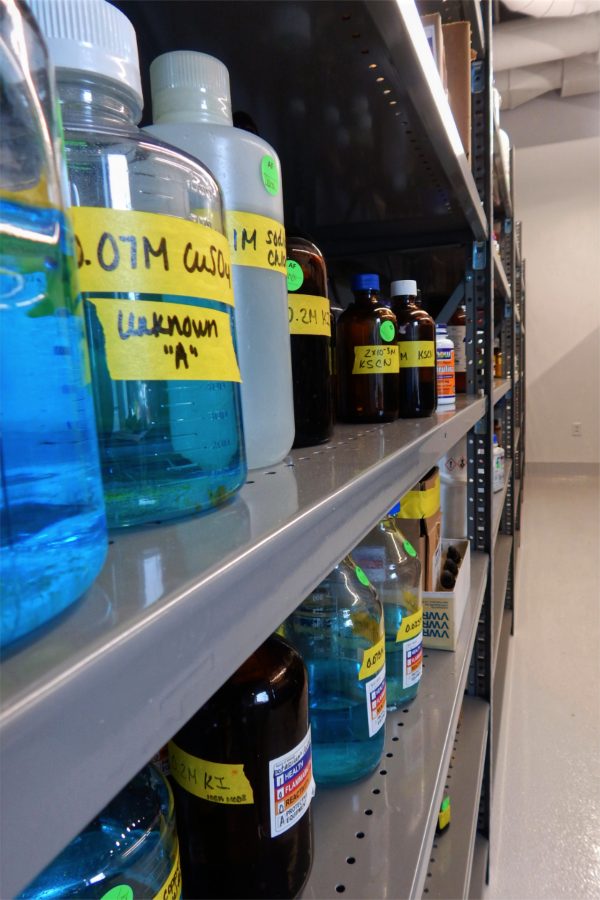

Two specialized firms handled the transfer of Bates assets from Dana to Bonney. Tobin Scientific of Beverly, Mass., shifted the science equipment, and Environmental Projects Inc. of Auburn, Maine, conveyed the chemical supplies. They have “done a fantastic job,” says Streifel.

Also deserving applause, says Streifel, is Bates construction administrator Jacob Kendall, a constant presence as the new building came together. “Jacob has been absolutely a monster in this move, just keeping everybody going. He’s got a real knack for this kind of thing.”

Bonney construction has largely dwindled down to the building-trades equivalents of crossing t’s and dotting i’s. Aside from an exterior pass still outstanding, primary punch-list inspections are finished and the project team has embarked on what’s called “back punch.”

Not the gesture of affection remembered so fondly from grammar school, this, instead, is making sure that corrections generated by the first round of inspections were done right.

Commissioning of the building’s mechanical, electrical, and plumbing machinery is likewise well-along, although, as Streifel points out, that barrage of inspections and tests won’t really be done till next spring: HVAC equipment, in particular, needs to be tested again with each change of season.

As for the few remaining chores at Bonney, there are finishing touches to apply inside and out, such as the installation of protective grates over the building’s sunken air intake, now concealed by a wall lettered with “Bonney Science Center.” And there’s plenty of landscaping to do, an undertaking made challenging by the persistent lack of rain.

In fact, it won’t be for another year or so that the science center really settles into its final appearance. That’s because the far end of the parking lot (an area formerly occupied by the two houses of the Bates Communications Office) will continue to house storage containers and other facilities supporting the Dana Hall makeover.

Oil’s well that ends well: Starting this winter, carbon-neutral Bates will use even less fossil fuel thanks to fried-food enthusiasts around the Northeast. (We’re happy to do our part!)

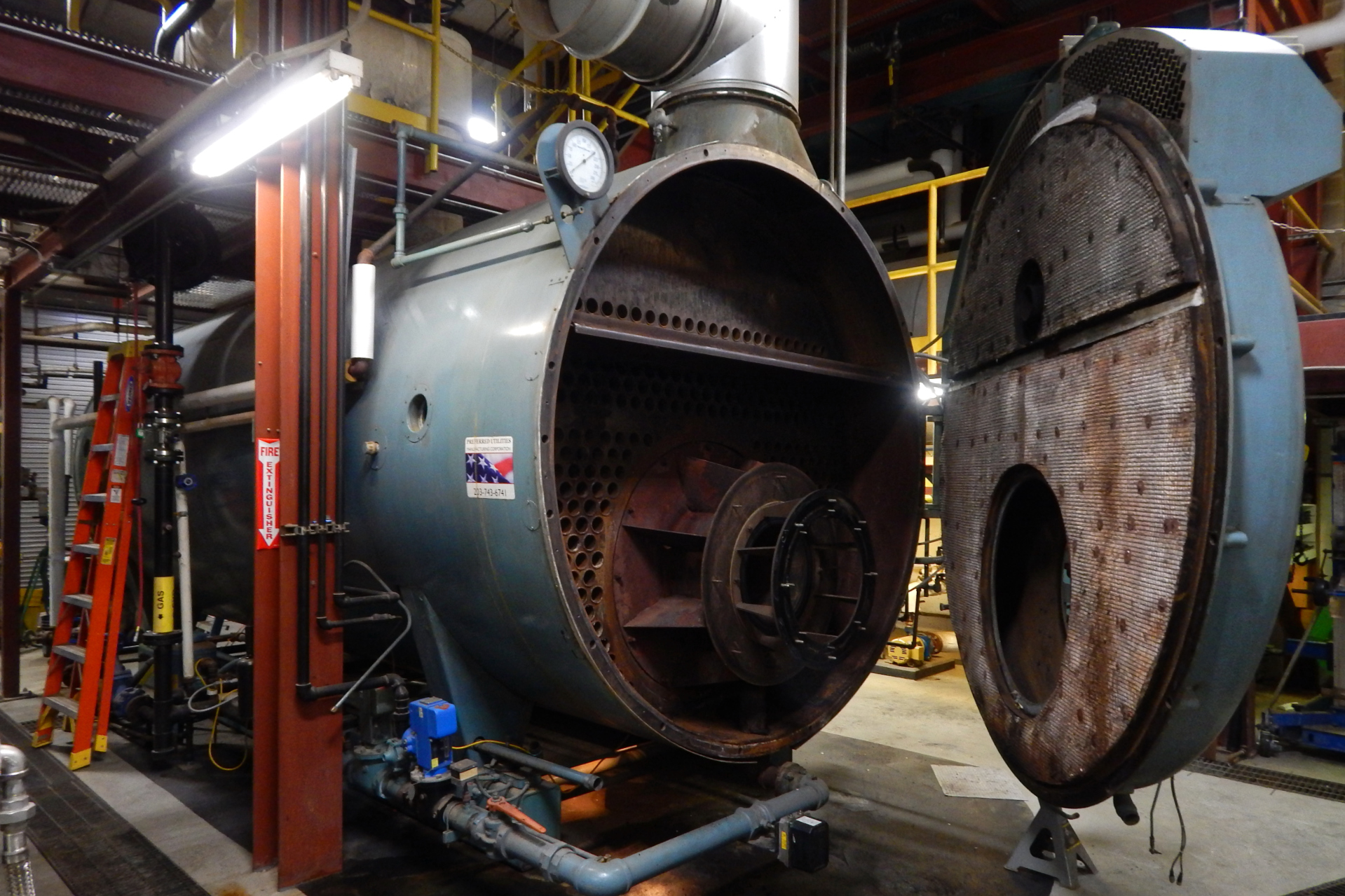

With two of the three boilers that steam-heat the central campus already burning a product called Renewable Fuel Oil, the college is converting the third unit for a different climate-friendly fuel: vegetable oil recovered from the food-service industry.

Lifecycle Renewables of Tewksbury, Mass., will supply the fuel, known as LR-100.

Bates’ use of LR-100 will be limited. Boiler No. 3 is a back-up boiler, operated when one of the others is out of service. Renewable Fuel Oil, made from waste wood products by the Canadian firm Ensyn, will remain the primary fuel for the campus steam plant’s two workhorse boilers.

“We prefer to burn RFO because it’s a wood-based product, and that helps our forest industry here in Maine and the Northeast,” says Bates energy manager John Rasmussen. “They’re in desperate need of a market for low-quality wood, pulpwood basically. The market has been reduced by 2 million tons a year” as the paper industry has contracted in recent years.

But “whenever there’s some supply disruption [with RFO], instead of using natural gas as backup, we can now use LR-100.” Lifecycle Renewables runs a sizable cooking oil collection network in Massachusetts and beyond — even cleaning grease traps for its clients and recovering that oil.

The initial conversion to RFO, in 2016, was no trivial matter, entailing the erection of a 20,000-gallon tank, installation of various equipment to make the oil burnable, and the refitting of Boiler No. 1 with an injector that can stand up to the acidic fuel. With the fuel-handling system in place, Boiler No. 2 just needed the retrofitted combustion components.

The No. 3 conversion for LR-100, though, is the simplest of all. The tanks once used for petroleum-based fuel oil just need cleaning prior to filling with LR-100, and the boiler’s burner gun is fine as is. So the only additions needed for the conversion are an inline heater to promote fuel flow and a system for measuring the efficiency of all three boilers. That’s all happening this month. (LR-100 will also work with boilers 1 and 2 with no modification — and all three boilers will remain dual-fuel, with natural gas as an alternative.)

That metering system, by the way, is a requirement of the state program that is making this conversion possible. As part of Gov. Janet Mills’ drive to curtail fossil fuel use, it offers a mechanism of “thermal RECs” — renewable energy certificates — to offset the cost of sustainable fuels, making them competitive with natural gas.

What prompted this project, Rasmussen says, was the desire to diversify Bates’ sources of heating fuel. Gallon for gallon, LR-100 is quite close to petroleum-based oil in heat content, and provides substantially more energy than RFO — some 128,000 BTUs per gallon vs. 80,000.

But RFO costs less. And either way, says Rasmussen, “it’s nice to know that we can basically eliminate fossil fuel use” in heating the central campus.

Better slate than never: Slate seems to be a theme for Hathorn Hall upgrades this summer.

For starters, the building’s slate roof is being replaced. G&E Roofing, of Augusta, Maine, is handling the project, which also includes new copper gutters and downspouts, as well as a new rubber-like membrane on the top of the belfry. Facility Services carpenters are pitching in by fabricating some massive new moldings for the Hathorn roof.

How old is the slate being replaced? “The jury is still out on that,” says Bob Leavitt, assistant director of maintenance and operations for Facility Services. “The best guess is pushing 100 years.”

He adds, “We’re very pleased to find that the majority of the roof structure itself is in excellent condition — very few places showing deterioration. So it was installed probably as well as you can imagine back in the day.”

A 2017 roofing assessment anticipated the slate replacement, which was scheduled originally for 2020 but delayed by COVID-19. In progress since early June, the job will be wrapped up by mid- to late August.

Leavitt estimates that 6,000 square feet of slate will be replaced. New England Slate Co. of Poultney, Vt., is supplying the product, which has been quarried to order — “North Country Black” at the Glendyne Quarry in Saint-Marc-du-Lac-Long, Québec, and “Vermont Purple” at the John Maslack Slate Quarry in Poultney. The colors match the original roof of the building, in keeping with its listing on the National Register of Historic Sites.

Meanwhile, a differently used variety of Hathorn slate is being superseded. “We’re replacing some of the chalkboards in Hathorn, old slate chalkboards,” says project manager Paul Farnsworth. “The faculty don’t like them. They’re small and they’re not at the right height. Some are cracked. Some are easy to write on but some of them are too smooth.

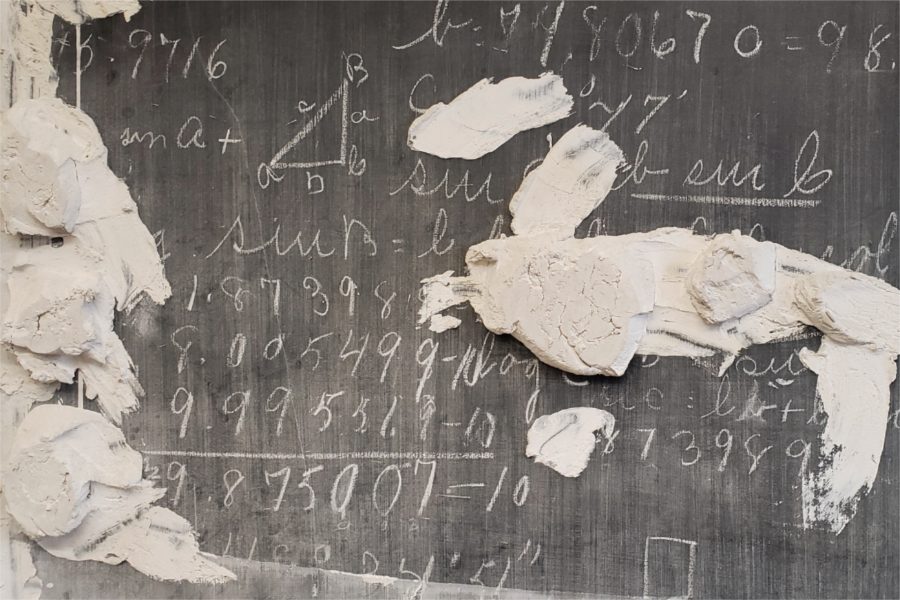

“Well, on June 21, we took down the first of what we thought were the original slate chalkboards.” And what did they find behind it? Another slate chalkboard — complete with math problems from some long-ago class session.

Farnsworth reckons that the surprise discovery must be one of the boards installed when Hathorn was built, in 1857. In all, Farnsworth’s crew found original chalkboards behind the existing units in two rooms, 303 and 305. (The cryptic inscription “Thank You” / “May 16—1892” appears on wallpaper uncovered in a different classroom.)

In the photo above, the white stuff slathered on the original slate is plaster of Paris or something similar, applied to prevent the newer board from bowing inward under pressure.

Farnsworth is replacing nine of the old boards and adding two boards to Hathorn’s total because, as he says, “everyone always wants more writing surface.” (Hence this 1,900-word Campus Construction Update.) The replacements are unframed porcelain-on-steel units. “They’re nice.”

“You can’t buy natural slate chalkboards anymore,” he adds. “We received positive feedback from the man-made sample we had for faculty and staff to try writing on.”

Supplying the boards is New York Blackboard of Hillside, N.J. “They are the people, as far as I can tell, that know chalkboards,” Farnsworth explains. “And they delivered them, instead of shipping them — two of the people that drove them up were the grandfather that started the company ages ago and his grandson.”

That delivery was in March. “They thought I was going to install them as soon as I got them, and they were all ready to help. And I was like, ‘I’m sorry to disappoint you. I’m just going to put them in storage.’”

Originally slated (sorry!) for 2020, the chalkboard work finally began a couple weeks ago and should wrap up early this month.

New cages for the Cage: With one complete and the second in progress, summer 2021 is bringing significant improvements to the Gray Athletic Building.

Complete is the installation of two new batting cages for baseball and softball. As Facility Services project manager Shelby Burgau explains, they replace units that weren’t quite spacious enough for their intended use, yet were so bulky as to create some concern about building egress.

Those old cages folded up against the interior walls at the Alumni Gym and Muskie Archives ends of the space, but when in use they were aligned along the wall adjacent to the Library Quad — a wall with three main entrances.

In contrast, when in use, the new cages are tucked in at the Muskie end. When not, they are collapsed and then hoisted up, up, and away into the rafters of the Gray Cage. “So they’re completely out of the way,” Burgau says. “They look a lot nicer, a lot cleaner, and you can put one down or both down. So now you can have a cage down, but still use the basketball courts.”

Consisting of nylon mesh and a metal frame, each cage is 12 by 72 feet. They were manufactured by Seaway Plastics, which has operations in Quebec and in New York state.

Meanwhile, in progress is the placement of a new floor in Gray, for which preparation began this week. The new surface will be a rubber multipurpose flooring manufactured by MONDO and installed by FJ Roberts–AASG Sports Surfaces of Wilmington, Mass. Installed directly atop the old floor, a urethane surface that in turn sits atop asphalt, the new 8mm product will be laid in 6-foot wide strips and fused together.

The new floor should be ready for action by mid-August.

Can we talk? Campus Construction Update welcomes queries and comments about current, past, future, timeless, and “that never happened — or did it?” construction at Bates. Write to dhubley@bates.edu, putting “Campus Construction” or “’Pampas’ rhymes with ‘campus’! Do I get royalties?” in the subject line.

Doug Hubley is a writer and musician living in Portland, Maine.