At some point in Friday’s NCAA women’s basketball tournament game between Bates and Roger Williams University, a Bates player will haul down a rebound and fire a pass downcourt to an open teammate for an easy layup.

When you see that, think of Frank Keaney, Bates Class of 1911, the University of Rhode Island coach who shocked the basketball world with a revolutionary, run-and-gun “fire-house” style of play — including his own invention, the fast break — that transformed basketball “as much as the forward pass changed football,” wrote Sports Illustrated in 1978.

Bates in the NCAAs

Bates takes on Roger Williams University in the first round of the NCAA Division III Women’s Basketball Championship at 5 p.m. Friday, March 4, at St. Francis College in Brooklyn, N.Y. The game is available via livestream.

A quirky, erudite, tinkering polymath who taught chemistry, too, Keaney deployed pithy aphorisms in Latin and English; invented URI’s school color (“Keaney Blue”) in his lab; and used ideas from Demosthenes and American philosopher William James to create a potent approach to coaching, one that instilled a sense of wonder and romance in his athletes: the “love of the seeking, the zest, the joy of the road to winning.”

Frank William Keaney was born in Cambridge, Mass., in 1886 to Irish immigrants. His mother died in a flu epidemic in 1900. By then, his father had abandoned the family of five children. Frank and brother Allan were raised by an older sister.

Attending Cambridge Latin School, he studied Latin and Greek and played football, baseball, and track. He picked up basketball, invented in 1891, at the local YMCA. Without parental supervision, he got in early trouble. “In the district court this morning, Frank Keaney was fined $3 for throwing snowballs,” noted the Boston Globe.

Graduating in 1907, he played semi-pro baseball in the Maine League for Lewiston. At season’s end, as Keaney prepared to head home, teammate Willard Boothby, already enrolled at Bates in the Class of 1909, introduced him to Bates President George Colby Chase, who asked Keaney about his goals.

“Teach and coach,” replied the 5-foot-8, 145-pound shortstop. Chase asked, “Did you study Greek and Latin?”

After Keaney quoted the opening verse of Virgil’s Aeneid and translated it, Chase admitted him on the spot. Joining a class of 138 from eight states (including South Dakota), he was one of few Catholics. Jumping into campus life, he played in the annual freshman-sophomore baseball game that fall, won by the frosh, 3–2, in a “rattling good game,” reported The Bates Student.

Then it was on to football, which was enjoying heady times. The year before, in 1906, the forward pass had been legalized, and Bates, under coach Royce Davis Purinton, Class of 1900, joined the vanguard. “The forward pass was attempted by the Bates team and was well handled,” the Student reported. “The play promises when perfected, to be especially pleasing to the spectators besides an effective ground gainer.”

In Keaney’s first game, against the soldiers of Fort McKinley, a bygone Army base on Great Diamond Island in Casco Bay, Bates won 34–0. The Bates backfield included two freshmen, Keaney and Eugene Vernon Lovely of Gardiner, Maine. It was an auspicious pairing: Both would one day have athletic stadiums named for them. (Note: They weren’t the first Bates backfield to achieve rare distinction after Bates: the 1904 tandem of Harry Lord and Bobby Messenger later played together for the Chicago White Sox.)

In October, Harvard pummeled Bates, 33–4, at Soldier’s Field in Keaney’s hometown. Harvard, one of the nation’s best teams, employed assistant coach Oliver Cutts, Bates Class of 1896, a Harvard-trained lawyer and All-American, who later returned to Bates as football coach and athletic director.

In November, at Orono, heavy rain made Alumni Field “resemble a clam flat,” the Student said. Bates tied Maine, 6–6. Keaney scored the touchdown on a 20-yard run, “dodging and evading several tackles.”

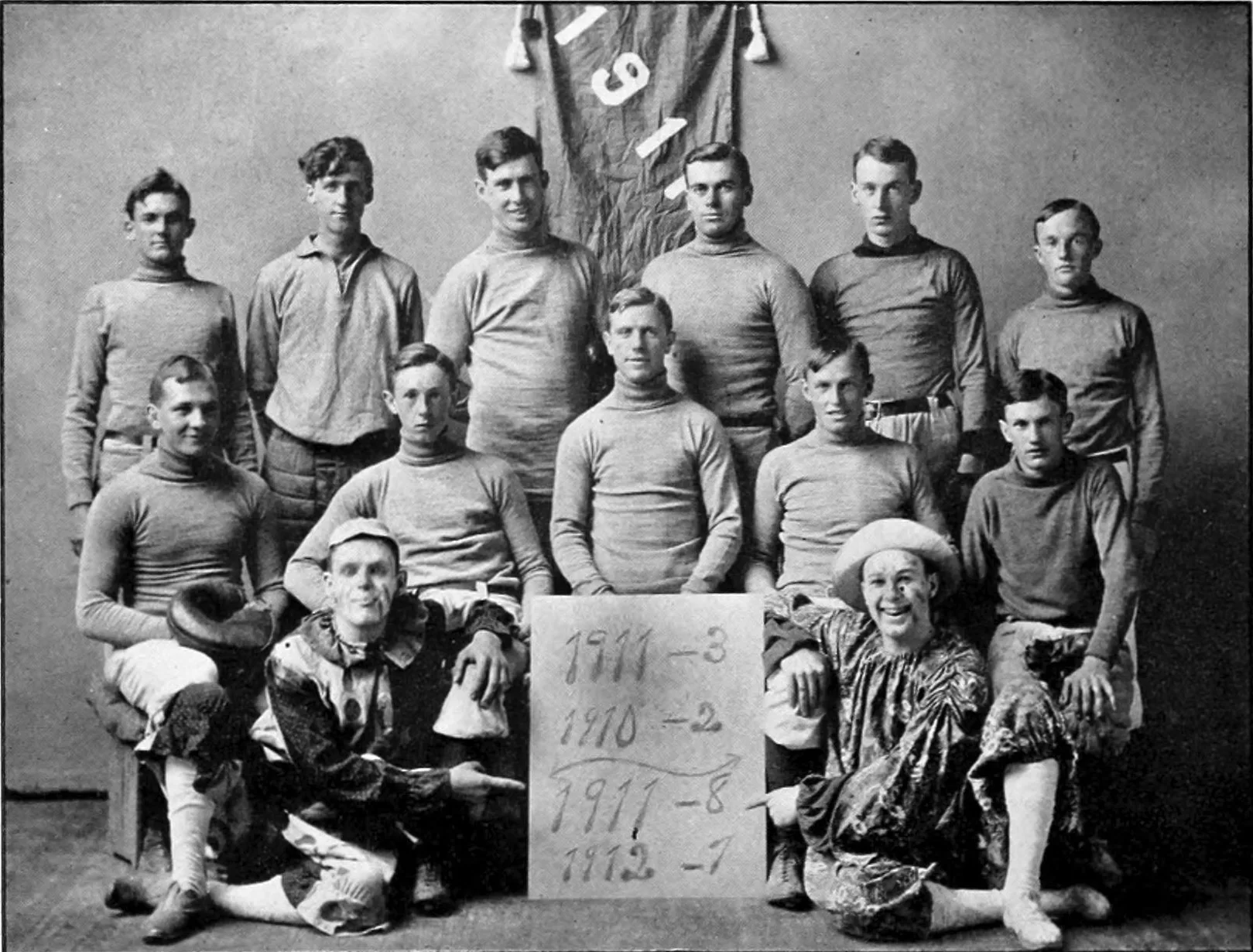

Bates finished 3-4-1, with Keaney awarded a varsity B, Lovely a freshman numeral, and Boothby, who had introduced Keaney to President Chase, promoted to manager next year.

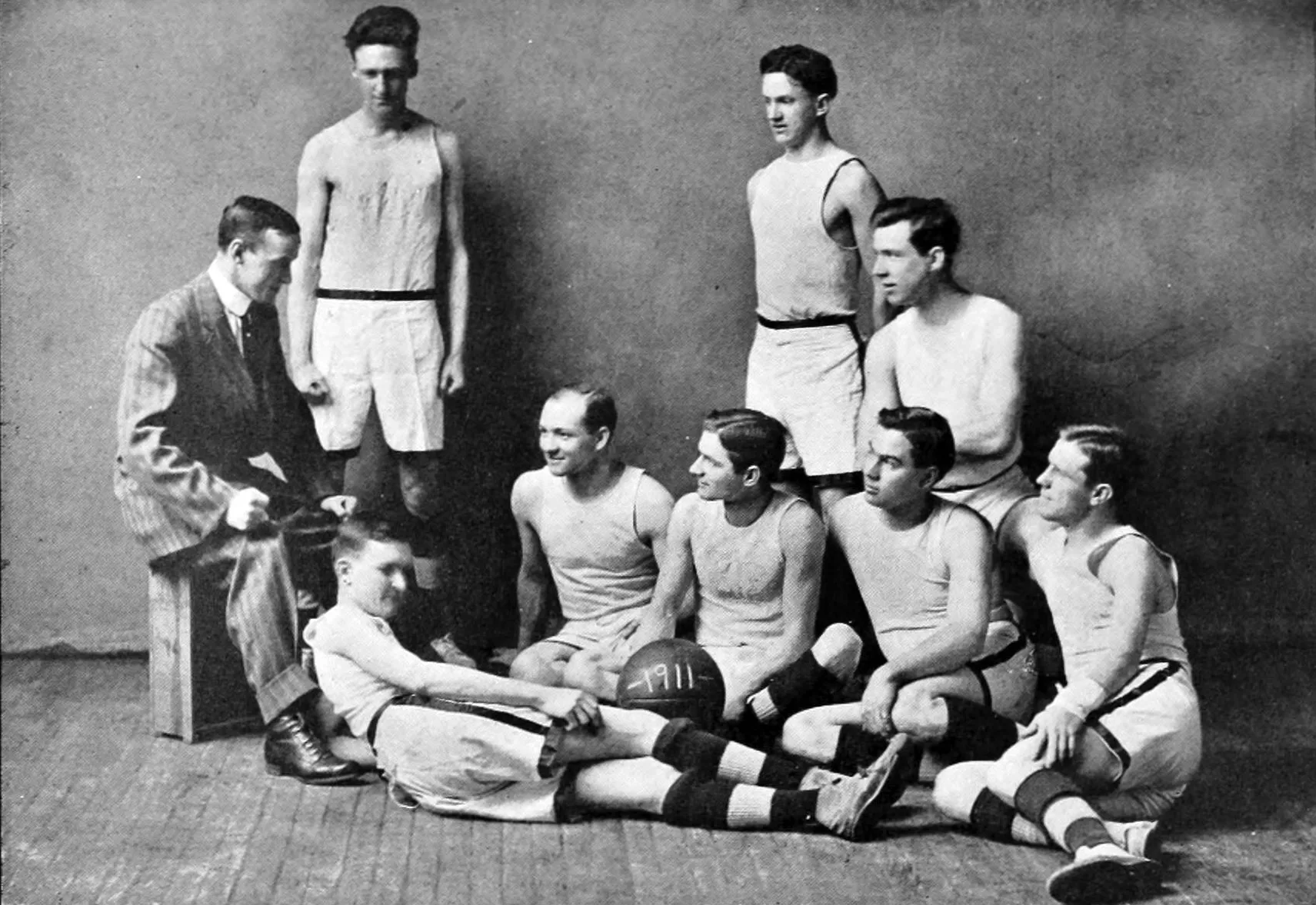

That winter, “the first season in the history of intercollegiate basket-ball” was played at Bates. Twenty tried out, including Keaney, “experienced in the game.” The first game, on Jan. 17, 1908, was a 52–18 loss vs. the Rockport YMCA. The first college game, a 21–7 loss to Colby, was at Lewiston City Hall. The finale, a 22–15 loss to Maine, was at the old wooden Bates gymnasium.

After a disappointing 3–5 record, the Student declared the inaugural season “handicapped by inexperience, incomplete organization, absence, and loss and change of captains.” A high-minded editorial went further, citing “objections for maintaining basket-ball at Bates as an intercollegiate sport.”

The primary objection was that the “best material” — i.e., the best athletes — already played football, baseball, or track, and were overstretched. “In the past those students who have had to sacrifice their studies for athletics have had a chance in the winter term to vindicate their ability as students. But with basket-ball included, the winter term holds out the same distractions from study.”

A decision was made. “Basket-ball” was dropped as a sport. Its return would come 12 years later, in 1920.

Keaney was one who could surely use the break. In his first year, he played football, ran track, played baseball, joined interclass competitions, and pounded the books.

He also worked. In his first year, tuition was $50 a year, and board was $3 a week. To pay for his board, Keaney washed dishes 20 meals a week for 60 students. On one Saturday, he dashed from the dish sink to Garcelon Field, where he “took the ball on a double pass around Bowdoin’s left end for 20 yards.” On Sundays, he mixed ice cream in an “old fashioned electric freezer with paddles.”

To pay for his room with amenities like “steam heat and electric lights,” Keaney cleaned out the lab in Hedge Hall, and two classrooms, and kept the coal fires burning in pot-bellied stoves. “At 6 in the morning I took out the ashes, carried the coal up two flights in coal hods. At noon I looked the stoves over. At 6 p.m. or at 7, I banked the fires, and at 10 saw they were O.K.”

An aspiring teacher, he taught in a one room schoolhouse between Thanksgiving and February. On campus, he studied Latin, Greek, chemistry, physics, and English.

As baseball approached, the Student predicted that “the Cambridge High man seems to be the fastest man to fill Captain Wilder’s old place at shortstop.” The team finished 11–8, with freshman Keaney batting .216, behind senior Wilder (displaced now to second base), who hit .320.

By junior year, Keaney was hitting his stride. In football he was named Second Team All-Maine, but with a caveat: “Some may pick him (first team) in preference to the Bowdoin man. Keaney’s play is decidedly of the spectacular order while Smith is perhaps more reliable.”

In the classroom, Keaney excelled in Latin and Greek. “He loved the structure of the language,” according to his biography, Keaney, written by William Woodward. “He learned to appreciate its potential impact in influencing others and making things happen.”

And in baseball, he led off and batted .380 with 38 steals, developing the swashbuckling style soon to become his trademark. Bates beat Bowdoin three times. In a 5–2 win, Keaney was “the star of the game,” the Student reported, with three hits and four stolen bases. In a 5–4 Memorial Day win, he had three hits, including a triple, and stole two bases. And in a 6–5 Ivy Day win, he stole home, “the feature for Bates.”

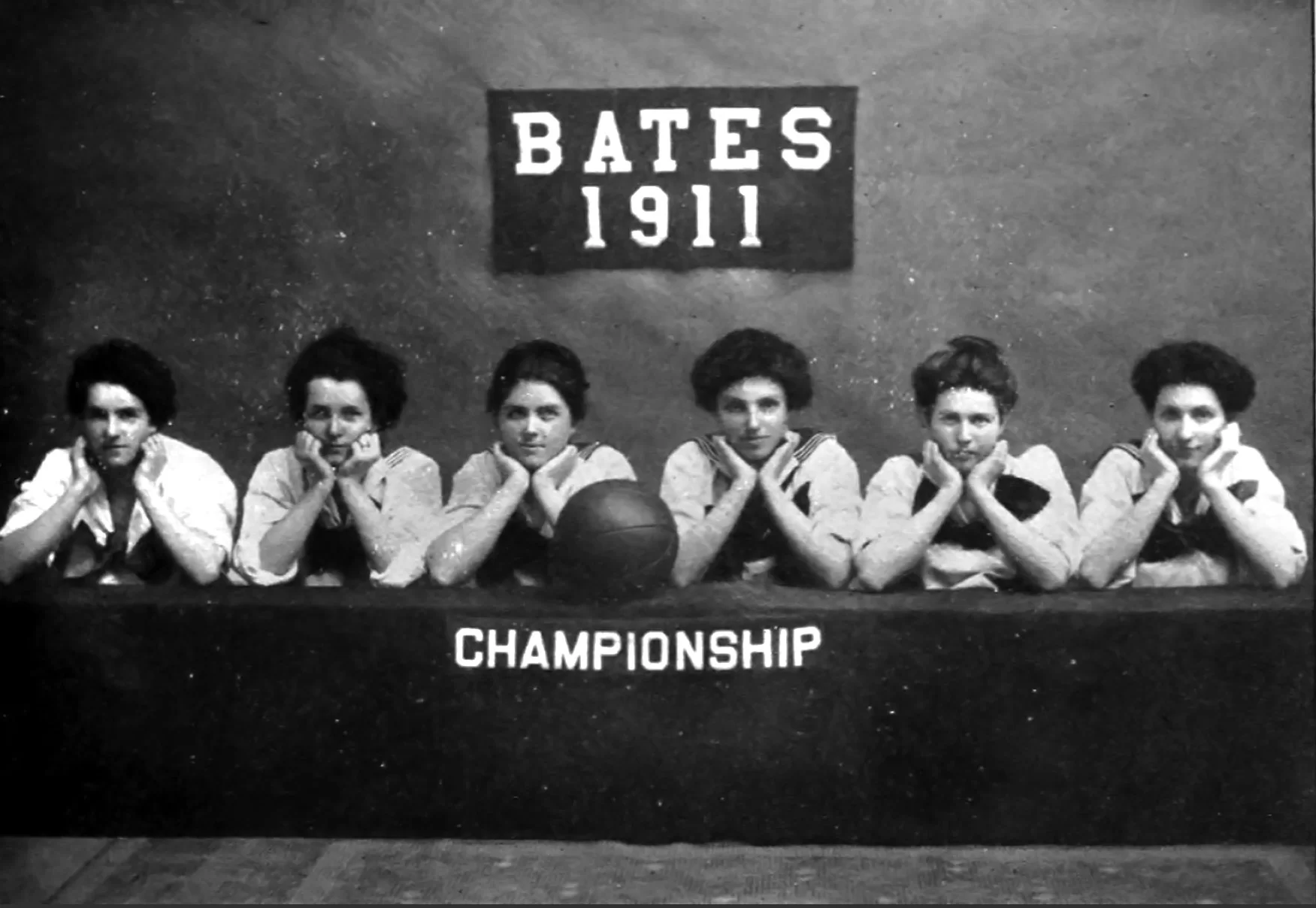

Keaney added another activity destined to change his life. As scorer for interclass girls basketball in the old Rand Gym, he watched the Class of 1911 defeat the Class of 1910 in overtime, 18–14, as “Miss McKee threw two baskets for the Juniors, winning the game.” He and Winifred “Mac” McKee, Class of 1911, of Newark, N.J., soon became inseparable.

Following his junior baseball campaign, Keaney was elected captain senior year, prompting a Boston Globe headline to gush that he was “not only a fine ball player, but is a brilliant student and popular.”

But days later, the papers published a shocking story that Keaney was headed to Chicago to try out for the Americans. Further, “Keaney could not be found at the college. His trunk had gone and so had he. None of the students could verify the story and all hoped that it was untrue, as a job with the Chicago Americans would debar him from college baseball another year.”

Keaney did not play in Chicago that summer (had he, he would have joined Harry Lord and Bobby Messenger, both Class of 1908, who played with the White Sox in 1910). Instead, he played for the Cubs — not in Chicago, but his hometown Cambridge Cubs, at shortstop. He never again played for Bates. “On account of financial reasons, he was obliged to play professional baseball during the summer vacation, thus making him ineligible,” the Student reported. He resigned as captain. Bates finished 10-5.

Interestingly, Bates had earlier students who played minor league ball yet retained eligibility. Prior to 1906, Bates was in the Maine Intercollegiate Athletic Association, whose rules and enforcement were haphazard.

In 1906, the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States was created, to standardize football rules — such as the “forward pass” — and make the game safer. Renamed the NCAA in 1910, the new entity established tighter eligibility rules, forcing Keaney from baseball in 1911, and making him an early casualty of “amateur” rules.

Senior season, football hopes ran high. But Keaney, “one of the best backs in Maine,” according to the Globe, chose not to play. “He prefers to give his entire time to baseball.” Two weeks later, came news that Keaney would coach the Gardiner High School football team, just up the road from Bates.

Why no football his last year? Was it the opportunity to coach? New-found love? Perhaps, but Cupid did not stop Lovely, who later married Isabell Kincaid, Class of 1911, of South Portland, from playing. The reason was NCAA eligibility rules once again, according to the Lewiston Journal. Bates finished 5-1-3, losing only to national champion Harvard, 22–0, at Soldier’s Field. Lovely, along with Keaney’s backfield replacement — his brother, Allan, Class of 1916 — led Bates to its best season since the undefeated 1898 team.

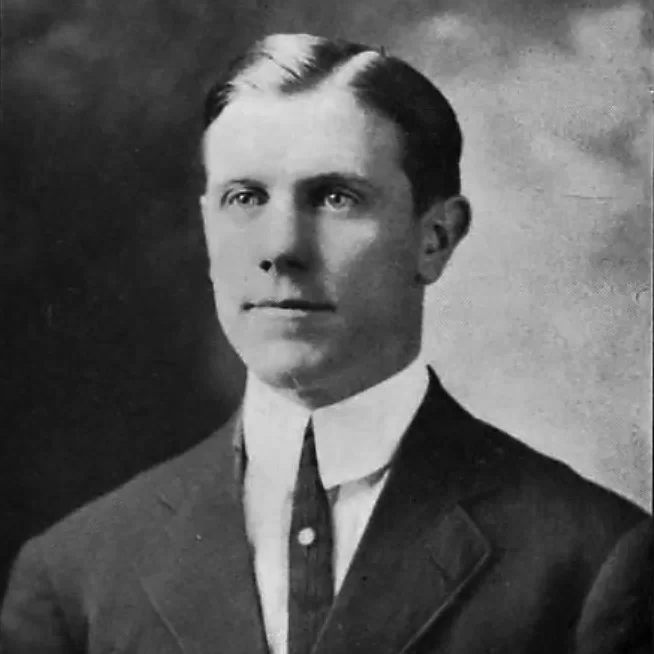

While courting “Mac,” Keaney kept busy as sports editor of the yearbook and led Bates to the YMCA basketball championship, beating Bangor 25–21 and Hebron 17–6. In baseball, Allan replaced him at shortstop. The 1911 yearbook listed Keaney’s three majors (Latin, chemistry, and English) and thesis (“The Sources of Petroleum”), but most telling was the poem beneath his photo:

He was always strong in athletics

Be it baseball, football, track

But during his last two years

He has given his time to win Mac

At Bates, Keaney was developing a philosophy that focused on human potential that would drive his career as a coach and teacher. He filled journal pages with ponderings.

Keaney was particularly taken by the ideas of William James, the father of American psychology. He was moved by James’ famous speech before the American Philosophical Association at Columbia University in 1906 in which he said that “compared with what we ought to be, we are only half awake. Our fires are damped, our drafts are checked. We are making use of only a small part of our possible mental and physical resources.”

In his journals, Keaney reacted to James’ thought with this question: “Do we ever go all out 100 percent?” As a coach and teacher, he would spend his life’s work wrestling with that question. At Bates, he had sown the seeds of all his future success: teaching, coaching, playing four sports, yielding to the NCAA, giving 100 percent, finding love. Bates had been a yeasty time; now he would rise to the challenges ahead.

Like many new grads, he took advantage of the Bates alumni network. C.C. Spratt, Class of 1893 and principal of Putnam (Conn.) High School, hired him to teach algebra, chemistry, and physics and coach all sports — for $900. Mid-year, he followed Spratt to Woonsocket (R.I.) High School with the same duties, but for $1,200.

Success followed immediately. His baseball teams won 77 straight; track won a state title; and basketball beat Reading (Mass.) High School, coached by brother Allan.

In 1914, he married Winifred, and sons Frank Jr. and Warner followed. In 1917, he moved to Everett (Mass.) High. By then, he had begun to perfect his philosophy: “Coaches and teachers should be full of ‘pep,’” he wrote. “They should love life and impart it…fun improves interest.”

Drawing on James, Keaney believed that athletes could awaken from their slumber and attain peak performance when, they were given “some unusual stimulus” — a challenge, funny pep talk, creative sports drill, or hard exercise — that “fills them with emotional excitement, or some unusual idea of necessity which induces them to make an extra effort of will.”

Ever the lover of language, he developed a colorful lexicon, dubbed “Keaneyana.” A 1941 newspaper article shared over 130 distinctive Keaney sayings, including his signature “Give me some Old Gazazza!,” which meant go all out, beyond limits. He would evangelize with anyone — the press, players, colleagues — about his work. Taking his cue from Demosthenes, he said the three most important things in speech-making are, “Action, action, action.” Keaney saw “action” as a chance to “show your true character… what you are made of. Action is fire and dash.”

In 1920, as basketball resumed at Bates, Rhode Island State College (which would become the University of Rhode Island in 1951) hired Keaney as a chemistry professor and one-man athletic staff. Founded in 1892, the college had hired its first athletic director in 1916, but three men quickly came and went.

“Keaney brought in ingenuity, dash, and flamboyance to the tottering athletic program.” His first year, football went 0–4–4, including a 27–0 loss to Brown. But basketball improved from two wins to 9-8, and rival UConn was beaten in three sports.

In 1925, the athletic staff doubled when Olympic hammer gold medalist Fred Tootell, a graduate of Bowdoin, was hired to coach track and assist in football. From 1925 to 1930, Keaney teams went 122–65, including 15–1 in basketball in 1929.

He coached football for two decades, and baseball for three. Even at 50, he could out-kick any player, including his sons, both Rhode Island kickers. Harkening back to Bates days, his baseball philosophy was: “If you run the bases with abandon, you will win.” His baseball record was 221–110–1.

But it was coaching basketball that brought national attention to Keaney and Rhode Island. For decades, the slow-paced college game had been seeking an identity, and Keaney provided it.

Inspired by the aggressive forechecking and outlet passing at a Boston Bruins game, Keaney “turned a game of patterned plodding into 40 minutes of frenzied excitement,” said Sports Illustrated. With the full-court presses, fast breaks, and long outlet passes, Rhode Island led the nation in scoring, and would do so in nine of 10 years in the 1930s.

In 1937, a rule change turbo-charged Keaney’s offense. Now, a jump ball following each basket was replaced by an in-bounds pass. With that, Keaney’s teams went from “point a minute” wonders to “two points a minute” marvels. Dubbed “firehorse” basketball, spectators loved it. In 1940, Rhode Island beat Connecticut 102–81 in the highest scoring game ever played.

“The system was deceptively simple,” Sports Illustrated said. “Rhode Island came out with a full-court man-to-man press and stayed in it the whole game. Whenever a Ram player got his hands on the ball after an opponent’s basket or in the back court, he heaved a long pass to a breaking teammate.”

Purists dismissed the pell-mell, fast-break style as undisciplined and too physically demanding. But writing in 1954, the legendary coach Red Auerbach lauded Keaney’s approach, saying it was based on the premise that a “team will normally score more points than the opposition if it gets more shots at the basket than its opponents.” Keaney’s team approached each possession as if there were just a few ticks of the clock left.

Keaney, the erudite polymath who taught chemistry as well as coached, dismissed critics with a Latin phrase, “nihil ex nihilo est nihil” — ”Nothing tried is nothing gained” — and pointed to the science behind his strenuous conditioning at a time when lingering belief that hard aerobic exercise could harm the heart. “A normal heart is never injured by hard work,” he wrote in his journal.” In Latin, he would yell to his athletes, “Elle conditio” — “Get in condition!”

Ahead of his time, Keaney explored the connection between physical conditioning and mental performance. A well-conditioned athlete, he wrote, “makes fewer errors of the head.” When an athlete performs at maximum physical efficiency, “arising problems in a game are quickly solved, fewer errors are made, and players are more attentive, more alive, and more alert.”

Not that Keaney’s own appearance reflected this. Long before Bill Belicheck made his hoodie chic, Keaney “ambled about on stubby, bowed legs, and his more-than-ample stomach sagged comfortably over his low-slung football breeches or sweat pants, with draw strings rarely tied. His attire also included a loose-fitting T-shirt or sweatshirt.”

Until 1941, “Little Rhody” was just a regional sensation; they’d never appeared at college basketball’s mecca, Madison Square Garden. That would end in January when “little, unknown” Rhode Island, according to the New York Daily News, came to the Big Apple.

His provincials had never even used a glass backboard, so he installed one at practice. Anticipating stage fright, he roared to his team, “Don’t be looking at tall buildings!” A special train, filled with fans, left Kingston for the national unveiling.

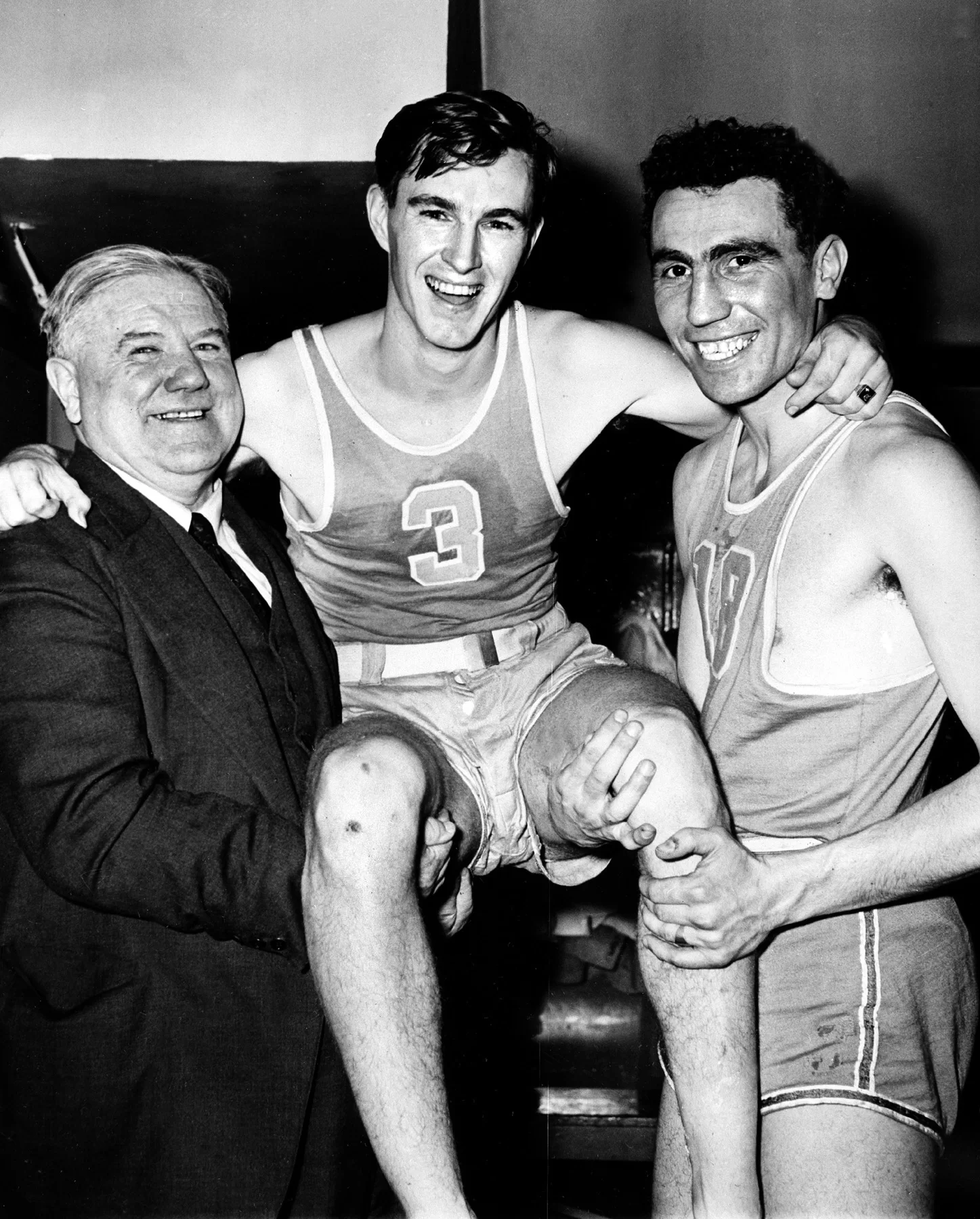

“Rams 42 points in First Half Sets Record at Eighth Ave Arena”; “RI Cagers Unorthodox Tactics Dazzle Garden Crowd — Lives Up to Ballyhoo”; “St. Francis Victim of ‘Racehorse’ Basketball”—headlines blared. His 6-foot-4, 270-pound son Warner led the team in rebounds.

In the war years, when Rodman Gym’s skylights were blacked out, the nation’s attention turned elsewhere. Frank Jr., a B-24 navigator, flew bombing missions over France and Austria. College basketball continued, but Keaney added another job, training troops on campus, inventing a toughening game called “murder ball,” combining basketball and football.

In the 1940s as throughout the mid-1900s, there was no such thing as March Madness, and the major men’s college basketball tournament wasn’t the NCAAs but the National Invitational Tournament, which vastly eclipsed the NCAA tournament in prestige and media attention, partly thanks to the tourney’s location, Madison Square Garden.

In 1941, 1942, 1945, and 1946, Keaney-coached teams earned invitations. In 1946, Rhode Island finished the regular season at 19–2 to earn its fourth invitation to the exclusive eight-team NIT to compete for the national championship. To prepare for smoke-filled Madison Square Garden, he placed “smudge pots” filled with cartons of smoldering cigars and cigarettes throughout the practice gym.

A shot from 62 feet out by Ernie Calverley tied the opener against Bowling Green before Rhode Island won 82–79 in overtime.

Next, they beat West Virginia. In the championship against Kentucky, coached by the legendary Adolph Rupp, the “Baron of the Bluegrass,” Rhode Island lost 46-45. Impressed by Keaney’s abilities, Boston Celtic founder Walter Brown offered him the job to coach his new professional team. Keaney initially said yes, but then decided to return to Rhode Island.

Keaney’s dazzling style was hardly confined to the basketball court or the baseball diamond. Indeed, “the fast break was only the most spectacular product of his maverick genius,” wrote Sports Illustrated. “There was a touch of originality in everything he did.”

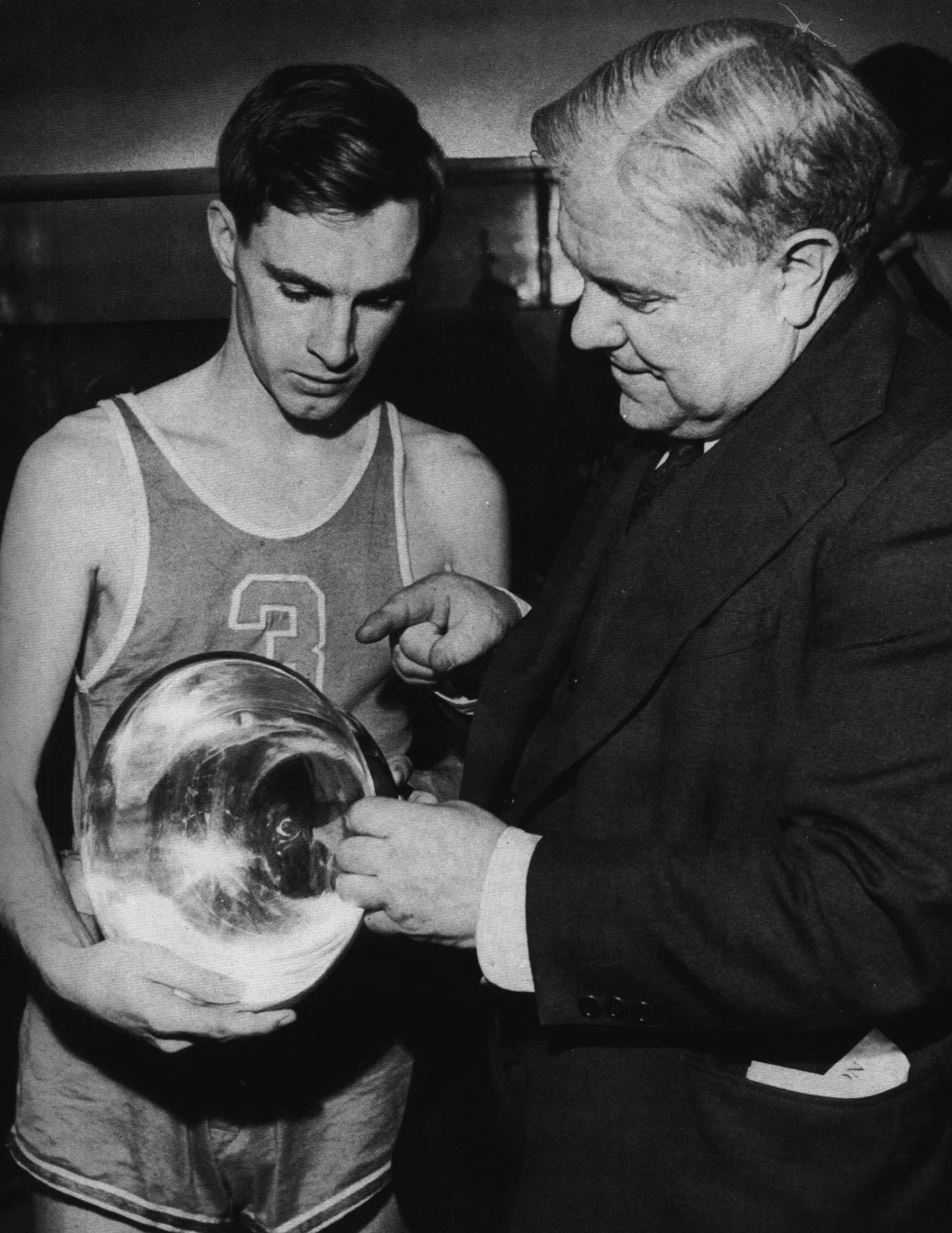

Ever the tinkerer, to promote sharpshooting, he devised the Keaney Ring, a 15-inch iron rim placed inside the standard 18-inch rim. “He loved to create and experiment, as was his modus operandi for his career as a coach.”

Keaney taught chemistry with the same passion and ingenuity. Some of his chemistry demonstrations were outlandish, like putting a tennis ball in liquid air (minus 321 degrees), then fire the ball at one of his athletes and laugh as the brittle rubber ball broke into a thousand pieces. He used chemicals in his lab to create powerful liniments for his athletes.

He once asked, “Why not a state high school championship in chemistry?” He then devised an exam and awarded trophies. With 300 competitors in 2018, the championship celebrated its 85th anniversary.

In his laboratory in Rodman Gym, he devised a new color, “Keaney Blue,” the school color to this day, “more pronounced than Columbia blue, more fluorescent than a Carolina blue,” said his biography. Unveiled at Brown Stadium in 1935, the new color heralded the first ever victory over Brown, 13–7. In celebration, he was hoisted on the shoulders of his “Keaneymen” and “carried the length of the football field.”

Keaney continued as athletic director until 1956. Across all sports, his record stands at 707–322–14. In 1960, Keaney was inducted into the Hall of Fame, a year after inventor Dr. James Naismith. “He was a wonderful, boisterous Irishman, an old-fashioned type coach who was half-father and half-Rockne,” wrote Woodward in Keaney. “He seemed to be saying to his players, ‘I’ll build your character son, you just listen to what I have to say.’”

In his forward to Keaney, Chuck Daly, who coached two NBA championship teams, as well as the 1992 U.S. men’s Olympic basketball “Dream Team,” wrote, “The game as we know it today places tremendous emphasis on conditioning, speed, quickness, tough defense, and sharp passing,” “[Keaney] introduced all these concepts 25 years before they became the norm.”

Red Auerbach called Keaney “a great psychologist,” hailing him as “very innovative and ahead of his time.” Sports Illustrated said he had “a restless imagination and flair for showmanship.”

In 1953, URI dedicated Keaney Gym, with 5,000 seats, on Keaney Road. But he isn’t the only one in his Bates backfield with that honor. At Andover (Mass.) High School, the football stadium is named for Eugene V. Lovely, honoring his contributions as a longtime science teacher, principal, and football and baseball coach. (His wife, three children, and two grandchildren all graduated from Bates.) “He probably influenced more 20th-century people in Andover than any other person,” a 2016 Andover Townsman story said.

All his life, Keaney filled dozens of notebooks chock-a-block full of diagrams, reflections, and verse — his own version of Leonardo’s Notebooks. From one, a poem “The Coach’s Wife,” he read at the dedication of Keaney Gym in 1953:

There are lines of praise to the athletic star

And the boys who make the team,

And the winning play of a crucial game

Has been many a poet’s theme.

There are headlines bold for the winning coach

And of how he directed the strife,

But here’s to a soldier behind the lines,

To the valiant coach’s wife….

Someone to rejoice when the victory’s won.

To share sorrow in times of defeat.

To have faith in the coach’s dreams and plans.

His alter-ego, who makes life complete.

So we laud the deeds of the coach and team.

Their success is the aim of her life.

She’s content to console, to exalt, to inspire.

And to be, just the coach’s wife.

On road games, he sometimes stopped the team bus in front of his home, strode to the porch and kissed his beloved Winifred “Mac” McKee Keaney before returning. Maybe there was a lesson somewhere there — more profound even than William James. They were married 53 years until his death, at age 81, in 1967. She died a year later.

Bob Muldoon ’81 lives in Boston. The author of the novel Brass Bonanza Plays Again, he has written a variety of historical sports features for Bates News.

![Title: [Harry Lord, Chicago AL, at Hilltop Park, NY (baseball)]Creator(s): Bain News Service, publisherDate Created/Published: [1912]Medium: 1 negative : glass ; 5 x 7 in. or smaller.Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ggbain-11489 (digital file from original negative)Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For more information, see George Grantham Bain Collection - Rights and Restrictions Information https://www.loc.gov/rr/print/res/274_bain.htmlCall Number: LC-B2- 2514-10 [P&P]Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.printNotes:Original data provided by the Bain News Service on the negatives or caption cards: Lord, Chisox.Corrected title and date based on research by the Pictorial History Committee, Society for American Baseball Research, 2006.Forms part of: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress).General information about the George Grantham Bain Collection is available at http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.ggbainAdditional information about this photograph might be available through the Flickr Commons project at http://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/2658871356](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2020/10/crop-Harry_Lord_ggbain-11400-11489u-200x133.jpg)