The Colby-Bates-Bowdoin football rivalry that kicks off Saturday afternoon was in its infancy when the mighty Nathan Pulsifer came across the Androscoggin River to enroll at Bates in the fall of 1895.

Organized football at Bates had existed for only two years. Colby had played five seasons, Bowdoin seven. Bates had not yet defeated its neighbor to the south.

But by the time Pulsifer graduated with the Class of 1899, the rivalry was renowned.

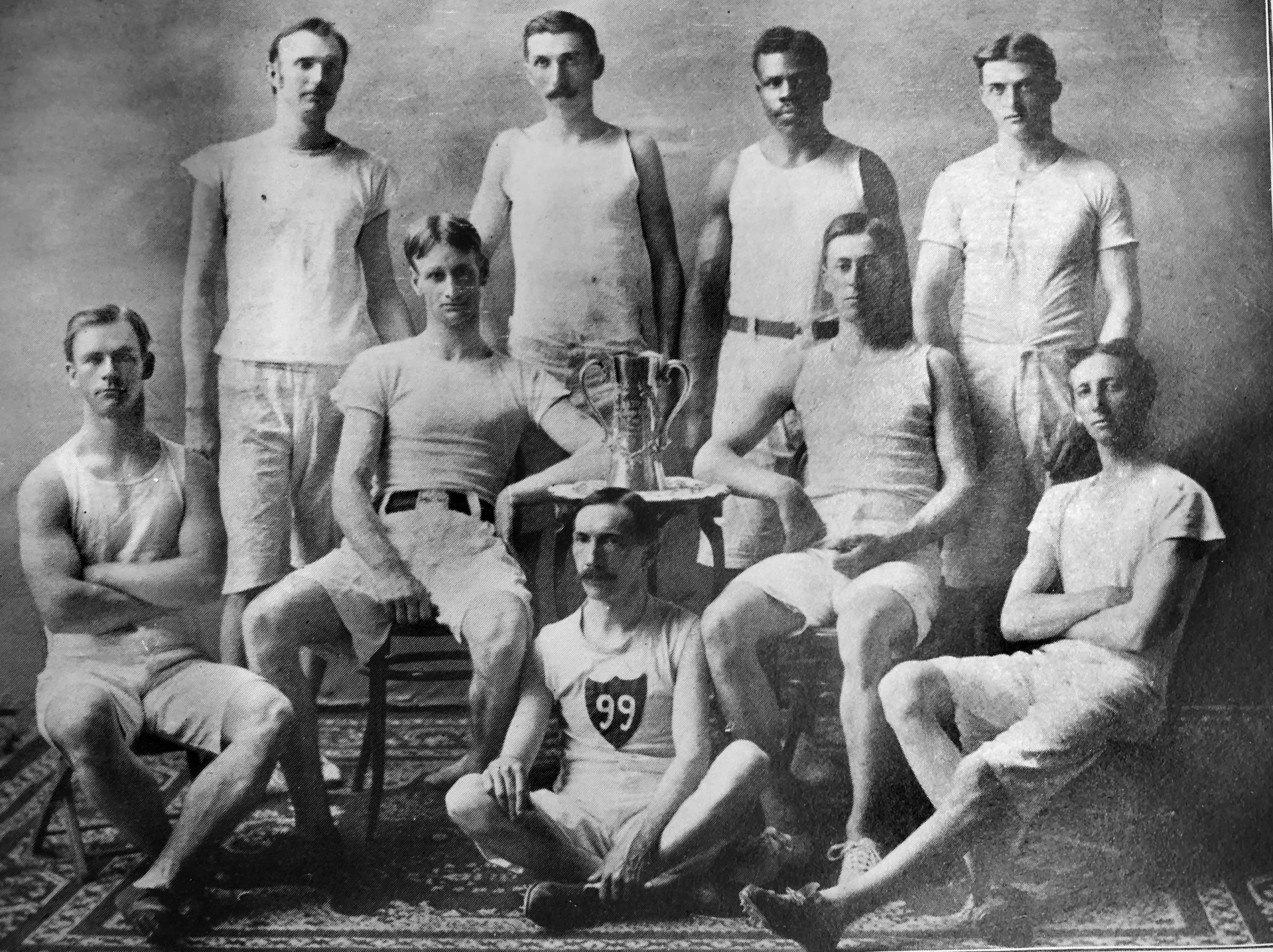

At Bates, in both football and baseball, his feats were Bunyanesque. Captain of the first two undefeated football teams in Bates history, 1 Pulsifer was a star running back who demanded that his teammates commit to the game.

Decades later, the head coach of the University of Wyoming football team declared Pulsifer the best player he’d ever coached.

CBB 2021

Watch the action live as the 2021 CBB football series kicks off at 1 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 31, with Bates taking on Colby at Garcelon Field.

In baseball, he hit the first home run at Garcelon Field — days after helping finish construction of the field, his hands still “blistered.” He was a debater, too.

After graduation, he played professional baseball, alongside the likes of Christy Mathewson, one of the first five members of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The first college graduate to manage a baseball team in the rough-and-tumble New England League, he once used his wits to avoid a forfeit by inserting a 9-year-old mascot in a game.

He served in World War I as a regimental surgeon, was a physician in Lowell, Mass., to Jack Kerouac, and inspired a character in one of his novels.

Born across the Androscoggin River in Auburn in 1876 to Augustus Moses and Harriet (Chase) Pulsifer, Nathan was the youngest boy of seven children. His father, a Bowdoin grad and lawyer, was treasurer of the Little Androscoggin Water Power Co., which owned an Auburn mill and provided water power to businesses along the river. His mother ran the household. Family life stressed education and achievement.

Before matriculating at Bates, Pulsifer attended the Nichols Latin School, a preparatory school housed in John Bertram Hall (graced then with a cupola), a school whose “special object…is to prepare students for the Freshman Class at Bates.”

Eligibility rules being loose back then, Pulsifer started for Bates at halfback while a 17-year-old Nichols student in 1894, eclipsing his older brother Tappan, Class of 1895, a substitute right guard. Nathan scored a touchdown his first game, four the next. Bates finished 4–1, defeating Colby twice but falling to Bowdoin, 26–0.

In spring, he played baseball alongside Tappan, going 2-for-5 in a 17–7 rout of Colby. Back at Nichols, he won a singles and doubles tennis tournament against Lewiston High School.

That summer, the brothers played baseball for Camden in the Knox County League, before Tappan headed off to medical school at Columbia University and Nathan crossed the Quad to officially enter Bates. In the largest first-year class ever (40 men, 39 women) to that point, he joined William Allen Saunders of Harpers Ferry, W.Va.

Together they would make Bates football history, but it would take time. In his first year, the football team, averaging 157 pounds, went 4–2, losing again to Bowdoin, this time 22–6.

Sophomore year, football dipped to 3–3–1, including a 22–0 drubbing by Bowdoin. Bates had never beaten Bowdoin — not even close. In four years, Bates had been outscored 124–6 by its larger, all-male rival. “Bowdoin administered her annual defeat to us,” wearily noted The Bates Student. “Pulsifer was the only Bates man to gain ground materially.”

In one early game, “Purinton sent Pulsifier round the end.”

In time, the duo of Lewiston-born quarterback Royce Davis Purinton ’00 and Pulsifier would form a formidable one-two punch on the gridiron and diamond.

In fine Bates tradition, Pulsifer debated. He argued the negative to: “Is it desirable for the United States to annex Hawaii?” In spare moments, he ran track and played tennis. It was a well-rounded Bates life.

About this time, a Brunswick-postmarked letter arrived from older brother Chase. A Bowdoin senior who had studied two years at Bates, Chase urged Nate also to transfer “because the athletics here are much better.” Indeed, Bowdoin football had never lost to any Maine team. Ever.

Pulsifer was unswayed.

Elected captain his junior year, he signaled resolve and formulated a set of team principles: “Captain Pulsifer has given out a few simple rules, which, if followed, will insure good results: Every man in bed at 10:30 p.m. Entire abstinence from tobacco and stimulating drinks; no pies etc., punctuality at practice.” The Student endorsed the draconian policies: “Let every student assist Captain Pulsifer to enforce the rules.”

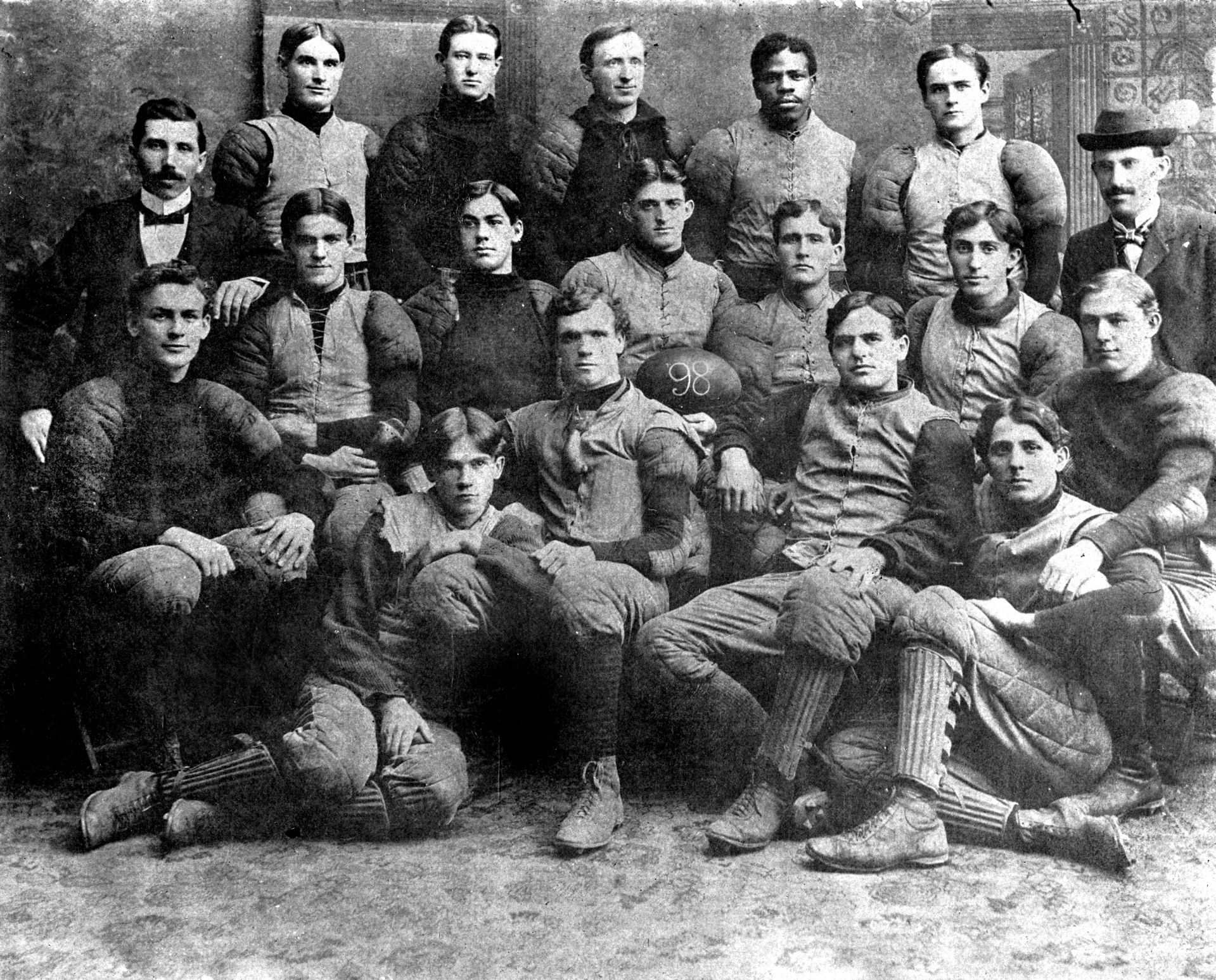

By 1897, all the pieces were in place. At quarterback, Purinton was field general and ball distributor (the forward pass was not yet legal). Pulsifer (5-11, 160 pounds) was running back. Guards Thomas Seth Bruce, Class of 1898 (6-1, 178 pounds) of Danville, Va., and Saunders (5-10, 173 pounds) were battering rams — who also ran the ball.

Bruce had graduated from Nichols behind older brother, Nathaniel, Class of 1893, who named his first born Bates Shaw Bruce, after his alma mater.

The fullback was “auburn-haired” Frank Halliday, Class of 1901 (5-6, 137 pounds), who also drop-kicked — at a time when a touchdown was four points, extra kick two, and field goal five.

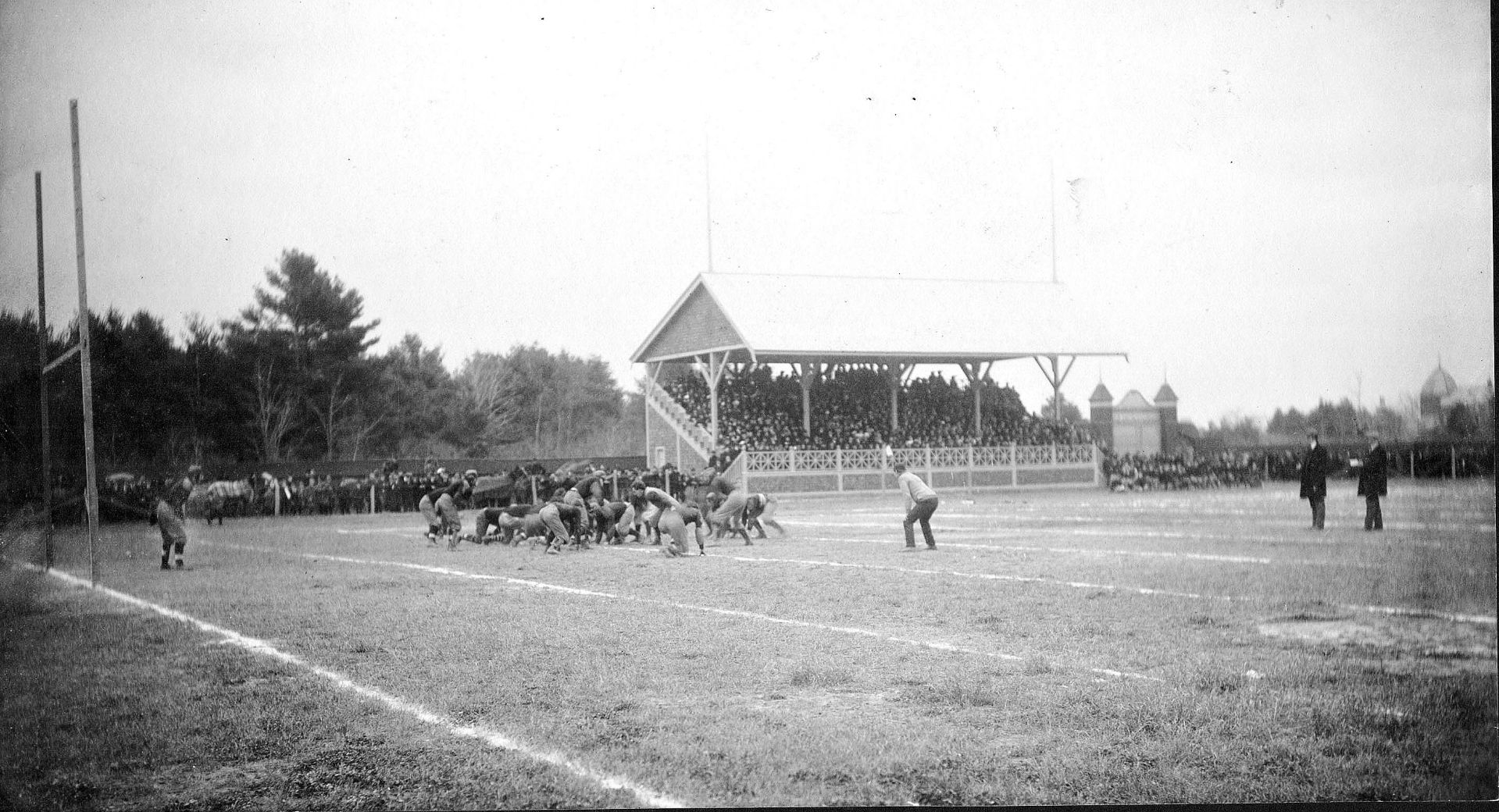

First up in the 1897 season: Bowdoin, away: “The grand stand had the biggest crowd ever seen at an opening game, and included a large portion of feminine Brunswick.” Yet Bates, at last, prevailed, 10–6. On the winning drive, “Captain Pulsifer followed his blockers around left end for 60 yards and a touchdown.”

Next: Maine, away: “The journey was very hard, particularly the nine-mile ride in the open electrics from Bangor to Orono in foot-ball clothes.” Down 6–0, Pulsifer tackled the quarterback for a safety, then scored the winning touchdown. Halliday kicked the extra two points for the 8–6 victory.

A week later, the two met again at Lee Park, Bates’ home before Garcelon, located near the intersection of Sabattus Street and East Avenue.

Down 4–0, Bates won on a last-play drop-kick field goal, 5–4. (Yes, a field goal beat a touchdown and missed kick!) “The city’s hum was silenced by the yells of college youth, who, bearing Halliday (the kicker) on their shoulders, marched down the street singing,” the Lewiston Evening Journal wrote.

Bates tied Colby 6–6, capping a 4–0–1 season, to capture the Maine Championship. Five Bates players made All-Maine, including Pulsifer, Saunders, and Purinton. Coach William Hoag, a Harvard grad, noted every player “gained not only in knowledge of the game but also in weight during the season” (the heaviest: 182 pounds).

Back on campus in 1898, the “Pulsifer Rules” were back in effect — with familiar enforcement mechanisms: “Now each student should see to it that these rules are obeyed; a man who breaks them should be criticized.”

At Bates, another winning season would take a village. Here’s a look at the six winning games of 1898:

Bates vs. New Hampshire State, Oct. 6

In the first game of the 1898 season, Bates pummeled New Hampshire State at Lee Park, 35–0, with Pulsifer scoring twice.

Bates at the University of Maine, Oct. 8

Next, they routed Maine in Orono, 36-0, with Pulsifer “who never seemed to get tired” running for five touchdowns, including a 65-yarder.

Bates vs. the University of Maine, Oct. 15

At Lee Park against Maine, Bates again dominated, 34–0, Pulsifer scoring three times. Bates’ record stood 3–0. Combined score: 100–0.

Bates at Phillips Exeter, Oct. 22

Bates beat Phillips Exeter, 18–11.

Bates vs. Bowdoin, Oct. 31, 1898

The showdown against Bowdoin at Lee Park was dubbed “Maine’s Harvard-Yale Game.” A bygone city commons, Lee Park also hosted traveling circuses, and the atmosphere that day was no less exuberant, Bowdoin students and townspeople flocking to the park.

“They left nobody behind but the college janitor, to ring the chapel bell when the tidings of victory reached Brunswick,” reported a confident Bowdoin Orient. More than 2,500 fans crammed the stands.

But the home team was also well represented. “Talk about your garnet! Garnet, garnet, garnet everywhere,” reported the Lewiston Evening Journal. Caps, hats, capes, buttonhole ribbons, parasol streamers — all ablaze in garnet. Across the field, Bowdoin ceremoniously unfurled its solemn white banner.

“The Bowdoin crowd was very confident of victory,” said the Orient. “They knew their team was strong, heavy, active, well coached, and possessing no end of grit and spirit. It had scored on Harvard, something no other small college has done in years.”

After kickoff, the pattern was set: “Saunders is playing like a fiend…time after time, the giant Saunders went into the line and always for a gain.” And “Captain Pulsifer played in his usual form and made several of his long runs.” At precisely 3:32 p.m., “Saunders took it six yards, with Pulsifer and Halliday with him,” for the lone score.

The extra points made the final score 6–0 in what was “universally admitted to be the greatest contest ever between Maine colleges.” Joyous students heading home “awoke the citizens of Lewiston and Auburn on the electric line.”

Bates vs. Colby, Nov. 5 (away)

With a second Maine Championship at stake, a bonfire on Mount David kicked off the finale against Colby. At Waterville, Pulsifer capped his career with two touchdowns in the 17–0 shutout.

Bates finished 6-0, unscored on by any college. Praise for the captain gushed forth: “Pulsifer is recognized as easily superior to any halfback in the state, and his long runs have been features of every game in the last two years.” Moreover, his “personal efforts and ambitions” had driven his team to dominance and elevated the college’s athletic standing.

Baseball could hardly equal it — but then came the uproar surrounding Pulsifer’s eligibility. And then his historic home run.

Perhaps still smarting from its football defeat the fall before, Bowdoin demanded that Pulsifer be barred from baseball in his senior year because he had already played four years, including his pre-college time at Nichols. (Bowdoin was perhaps also peeved because one of its players had been ruled ineligible.)

“May every building upon our campus be a pile of ashes before any college of the status of Bates be permitted to hoodwink Bowdoin,” protested the Orient.

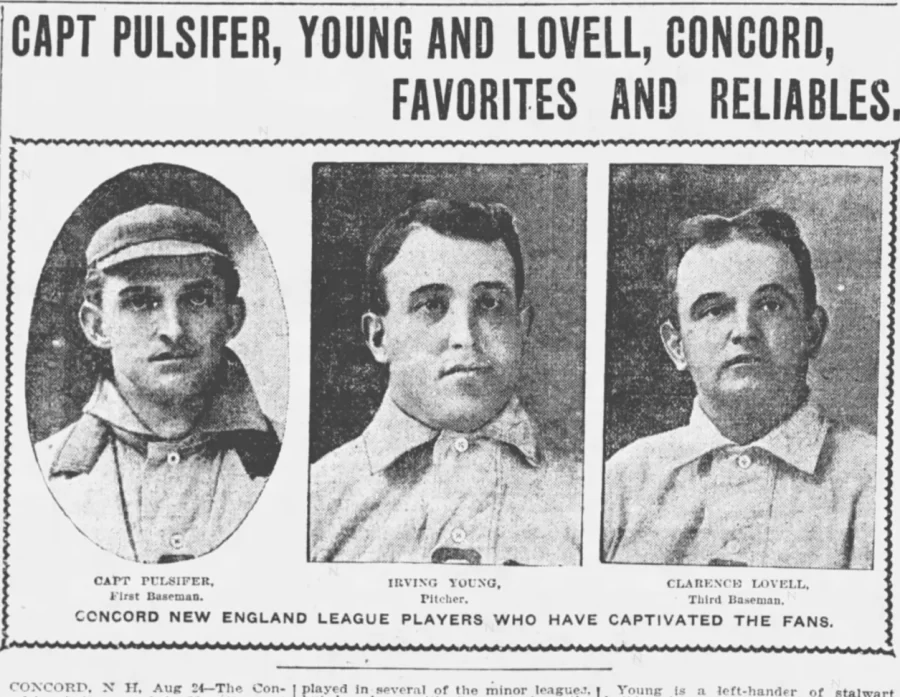

Bates kept its cool, citing the fact that a majority of “base-ball managers of the Maine Intercollegiate Base-Ball League” — Bates, Colby, and the University of Maine — had decided that “according to the rules of the constitution…Captain Pulsifer of Bates should, being eligible, be allowed to play on the Bates team.”

But now all eyes were squarely on Captain Pulsifer, and his final (fifth) season.

In spring 1899 — Pulsifer’s senior year — Garcelon Field was completed. President George Colby Chase’s annual report praised its aesthetics and economics. “One of the most satisfactory changes has been the grading of the former ugly pasture field east of Roger Williams Hall and its conversion into Garcelon Field with its ample grounds and tasteful grandstand…at a cost of $8,000.”

The project “would have required nearer $10,000 but for the enthusiastic help of students in removing stumps and in grading.”

The Bates Student lauded the laborers: “We all had a hand in transforming the rough uncouth pasture into this fine level park. Even the cedar posts surrounding it stand as monuments to the blistered hands, aching limbs and weary bodies, which we carried home after the day’s work.”

On May 30, against Bowdoin, Captain Pulsifer christened the new field with his clout: ”a drive to center field, which proved to be a home run, because of the fielder’s inability to field the ball, which had gone into a ditch in the rear of the yet-unfinished field.” The Lewiston Sun added cheekily, “Pulsifer’s home run isn’t done every day — neither is there so convenient a place to lose the ball.”

Late innings saw “choking, blinding, suffocating clouds of dust (that) rolled up from the new clay field. But when the dust lay quiet, the scene was one to inspire both artist and poet.”

Year after year, Pulsifer’s baseball talent had been getting more attention.

After a season in the Knox County League, he moved to Lewiston in the Maine State League after his sophomore year. “Pulsifer to the rescue,” shouted The Boston Globe on June 10, 1897, reporting on his bases-clearing, game-tying double vs. Rockland. Upon scoring the game-winning run, “he was carried on his shoulders by his admirers.”

After his junior year, having been elected senior class president, he reported to Hartford of the Atlantic League, under John Francis “Phenomenal” Smith, a 33-year-old ex-major league pitcher who became a mentor.

After graduation, Pulsifer and Purinton played ball for the Portland Phenoms, named for manager Phenomenal Smith. Pulsifer then took a coaching position at Hebron Academy. He then became math instructor at Dean Academy in Franklin, Mass. — just as brother Tappan opened his medical practice in Berlin, N.H., in logging country, where horrific lumbering accidents often occurred.

For seven years, he taught and coached at Dean, playing baseball in the summer. In 1900, he headed south to the Norfolk Phenoms in the Class D Virginia League, again under Smith, who also recruited 19-year-old Christy Mathewson of Bucknell College. With Mathewson going 18–2, and Pulsifer batting .303 with five home runs and 22 steals, Norfolk won the pennant going away, with a 43–14 record.

“One so clever as Pulsifer should look for faster company than his present associates, for surely he is the best left fielder that ever played in the Virginia League,” the Virginian-Pilot wrote. “There is a score of fielders in the Big League who can’t hold a candle to Pulsifer, and although fans would regret to lose him, still they would be glad to hear of him associated with some National League team.”

Weeks later, that prediction came true — but for Mathewson, who signed by the New York Giants in September. Although the Giants later signed Pulsifer, in December, he remained at Dean Academy — and stuck in the minors.

In 1901, he followed Smith again, to the Class C Norfolk Skippers. From there, he bounced to Tarboro, N.C., then back to Portland. He was spinning on the minor league gerbil wheel.

The next three seasons, he played for the Concord Marines, created after a trolley line was extended north from Manchester. In 1904, at 27, he became player-manager, the first college graduate to “be given the entire charge of a New England League team,” according to The Boston Globe. Playing first base and outfield, he batted .282 with 138 hits, including seven triples and 52 steals.

Pulsifer became part of baseball folklore when he inserted a 9-year-old boy into a game to avoid a forfeit in Lowell. Concord had only brought 10 men. After one suffered an injury and one was ejected, Pulsifer was down to eight players.

“It looked as though the game must be forfeited when young George Diggins, age 9, stalked forth in his miniature mascot’s uniform and offered to stop the gap,” wrote Charles Bevis in The New England League: A Baseball History, 1885–1949. Diggins struck out, played right field, and was paid a dollar. Concord lost, 5–4, and newspapers called it a “farce.”

In 1905, he headed to Sioux City, Iowa, to play in the Class A Western League. “Two more college men were added to the ranks of the Packers. Modest in mien and conversation, both Pulsifer and Hatch (of Brown) are ornaments of the great profession of baseball,” the Sioux City Journal noted. The story dubbed Pulsifer “occupant of the chair of math.”

Notwithstanding his learned pedigree (and 91 hits), he was released in the off-season.

In 1906, he returned to the Class B New England League as player-manager of the Haverhill (Mass.) Hustlers, hitting .271 in 91 games at first base.

By now in his late 20s, Pulsifer’s life was about to change. Perhaps at the behest of his family and their high expectations — his brother, Tappan, had earned a medical degree from Columbia, in 1899 — he left Dean Academy in 1906, heading to medical school at Cornell.

But still he clung to baseball, playing two more years, with Haverhill in 1907 and the Lynn (Mass.) Shoemakers in 1908, after which he was released with this epitaph from the Fall River Globe: “His hitting (.181) has been woefully weak.”

He owned his failures — blaming only himself, noted the Lynn (Mass.) News. “He says this is the first time he has been let go in the middle of the season but manfully declares he can only take himself to task for the event.”

At 30, he was out of professional baseball. His star had set, as rising former Bates stars Harry Lord and Bobby Messenger, both of the Class of 1908, were on their way to the majors.

The withdrawal must have stung. After two years at Cornell, he left to serve as athletic director at Tufts, “with charge of all branches of athletics except track,” the same position Royce Purinton had at Bates. He stayed a year, coaching football to a 1–6–1 record and basketball to a 10–5 record.

But more changes were coming. In 1909, he married Edith Coggeshall, of Lowell, an art teacher at Dean. After returning to Cornell to finish his medical studies, he and Edith settled in Lowell, a bustling mill city on the Merrimack River. Their only child, a daughter, Edith, was born in 1911.

But sports still beckoned. From 1914 until World War I, he coached Lowell High School. “Doc has been out of the limelight for some time and no doubt relishes the chance to get back for a little spring work on the diamond,” reported the Fall River newspaper

During World War I, he served with the Medical Corps, earning promotion to major and serving as the regimental surgeon for the 340th Infantry. Serving near Toul, France, he wrote home of “the thunder of heavy bombardments from battlefields.”

Meanwhile, former teammate Royce Purinton had left Bates to serve with the YMCA in France, directing soldier-welfare programs. He also went to the front lines where, in two days of fighting, according to the Student, he witnessed the loss of 1,800 men.

Both returned in November after the Armistice. Purinton, perhaps shattered by his experience, died months later, at 41, leaving a wife and two young children. All of Bates mourned.

Pulsifer returned to private practice in Lowell, where he also served on the surgical staffs of three hospitals, including Lowell General Hospital.

In 1923, he testified in an illegal surgery trial that left a woman seriously injured. His diagnosis was “abortion followed by peritonitis,” reported the Fitchburg (Mass.) Sentinel. “He expressed the opinion that if such an operation were done by a competent physician…he would not expect septicemia to set in, except rarely.”

Around this time, Pulsifer encountered the family of future beat writer Jack Kerouac

In 1926, Pulsifer diagnosed the cause of death of 9-year-old Gérard Kerouac, Jack’s older brother by five years, as “purpura hemorragica” — a horrible bleeding disorder that caused the boy to choke to death on his own blood.

Pulsifer’s presence in the Kerouac home made an impression on 4-year-old Jack. In his novel Visions of Gerard, a meditation on the life and death of his brother, Kerouac describes one character, Dr. Simpkins, who “came and went with his old fashioned satchel and his listen-tubes and pipes and pills and pumps and surprised us all by his gravity and inability to speak.”

Alas, “the big doctor betakes his black suited bulk out of that house of sorrows and goes home, having given up hope a long time ago.”

A decade-plus later, when Kerouac was a star running back for Lowell High School, Pulsifer served as team physician. Perhaps Kerouac recognized the tall, grave figure alone at the end of the bench, surrounded by a small pack of Scottish Terriers he bred.

Perhaps Kerouac remembered how, with each injury, both dogs and doctor raced onto the field to attend to the fallen player. Pulsifer’s grandson Jon MacDonald described the dogs helping to “lick the player better.”

After the Depression, Pulsifer’s finances declined. Jon remembers trips to the country to collect vegetables from patients who could not afford payments. Grandson Bruce MacDonald recalls how “Papa treated people for next to nothing.”

After his daughter’s divorce, Pulsifer took in his two young grandsons and their mother. The boys found their grandfather “taciturn and distant,” much like Kerouac’s Dr. Simpkins. “Papa” would send them out with a box and shovel to collect manure from the scrap iron man, who used a horse and wagon, to fertilize his potato garden.

By the 1940s, Pulsifer was suffering from age-related dementia. His grandsons helped him clean out his office, shuttering a 37-year medical career. At home, as his condition worsened, he became unmanageable. He died at the Worcester Veterans Home on Aug. 5, 1950.

He is buried in anonymity at Edson Cemetery, 50 yards from Kerouac’s celebrated grave — about the distance of a Pulsifer touchdown run around end.

In 1920, a reporter asked the head coach of the University of Wyoming football team to name the best player he ever coached. “Nate Pulsifer, Bates College, Maine” replied John Corbett, who had coached Pulsifer at Bates just one year, his sophomore season.

In 1936, Nathan Pulsifer was named halfback on the All-Time Bates Eleven team, alongside Purinton, Saunders, and Halliday. 2

Today the four teammates are forever etched in immortality on the Pulsifer paperweight, donated by his two grandsons — both Bowdoin grads — depicting Saunders’ famous touchdown in Bates’ 6–0 upset of Bowdoin in 1898 — the greatest Bates game ever.

Blanche Sears, Class of 1900, wrote this verse to celebrate the win:

For though Bowdoin was old Bowdoin — when Bates was but a pup

They will find that Bates can bite as well as bark

So with sorrow running over is each Bowdoin student’s cup

And they think of six to nothing and Lee Park.

End Notes

1. Though the famed 1946 football team lost its final “game,” the Glass Bowl vs. the University of Toledo, that game is considered a post-season exhibition contest. Thus, the 1946 squad, which went 7-0 during the regular season, is considered one of Bates’ three undefeated football teams.

2. Scottish-born Frank Halliday transferred to Dartmouth after the 1899 football season. He played fullback for a year and graduated in 1901. He became a professor of law at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

The author would like to dedicate his research on this project to the memories of the late Dave Linehan ‘82 and Jerry Donahue ‘82.