A selection of recent mentions of Bates and Bates people in the news.

Stephanie Folarin ’04

Profiles in education: A chat with Wye River Upper School’s Stephanie Folarin — The Chestertown Spy

The Chesterton (Md.) Spy interviewed Stephanie Folarin ’04, who is the newly appointed head of Wye River Upper School, a college preparatory school serving students who face learning challenges such as dyslexia or ADHD.

Folarin explained that an important part of her school’s work is educating parents to understand that they can indeed “connect with a child who learns so differently from you and interacts with the world so differently than you. You can make a connection. But it will be a different kind of connection.”

And sometimes, the parent struggles more than the child “because they want to fix it. As parents, we want to fix it.” At Wye, “we want to work with parents,” helping them know what resources are available and how to access them.

- Read and watch the story: “Profiles in education: A chat with Wye River Upper School’s Stephanie Folarin,” The Chestertown Spy, Jan. 17, 2022

August Buschmann, German faculty

Maine’s largest Norway spruce lives on a farm in Lewiston — Lewiston Sun Journal

In a story about the state’s largest Norway spruce tree, the Lewiston Sun Journal notes that the tree lives on a Lewiston farm that Professor of German August Buschmann bought in 1939.

The 30-acre Christmas tree farm is now owned by Buschmann’s son, Ed Buschmann. The elder Buschmann, who died in 1986, was a professor of German at Bates from 1928 to 1971.

The spruce is the tallest, but isn’t listed on Maine Forest Service records because it’s not indigenous to North America. That’s no matter, says reporter Joaquin Contreras of the Sun Journal. The tree symbolizes “Buschmann’s affinity for the outdoors and passion for his current line of work.”

- Read the story: “Maine’s largest Norway spruce lives on a farm in Lewiston,” the Sun Journal, Jan 17, 2022

Tyler Harper, environmental studies faculty

Silicon Valley won’t save us — Slate

In an opinion article for Slate, Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Tyler Harper notes the conventional wisdom that the film Don’t Look Up, which tells a story about scientists trying to raise awareness of a comet heading toward earth, is an allegory for human, scientific, and political response to the climate crisis.

But there’s much more, says Harper. The film should remind us that “the human species is threatened with extinction on multiple fronts.” There’s climate change, of course, “but also renewed tension among nuclear powers,” the “possibility of malevolent artificial intelligence,” and, of course, pandemics for “which COVID may be a mere dress rehearsal.”

What these threats share, Harper says, is the “woeful” response we’ve seen. For example, Harper looks at one character in Don’t Look Up who thinks he’s discovered a way to make money from the impending comet disaster. That’s comparable to Elon Musk’s SpaceX investments, Harper says.

In the end, the film offers “a prescient warning: about the hubris of billionaires, the corruption of politicians, a myopic American culture that gives rise to both, and a nation that is woefully unprepared to lead the world in the face of any existential risk, whether the threat be climate change or a careening comet.”

- Read the story: “Silicon Valley won’t save us,” Slate, Dec. 22, 2021

Brittany Longsdorf, multifaith chaplaincy

How solitude is experienced in different ways — Maine Public

Multifaith Chaplain Brittany Longsdorf joined Maine Public’s Maine Calling for a segment about the human need for solitude, and how that’s different from loneliness.

“Solitude is often a choice, and has a set of intentions around it,” Longsdorf said. Loneliness, on the other hand, is not usually by choice, and often includes “a deep longing for connection to other people.”

Solitude is “really a longing for reconnection with yourself,” she added. It’s about intentionally “entering into a space by yourself because you want to, and to use that space as a means of reflection and deeper connection to yourself, or your purpose, or whatever you might hold as sacred or bigger than yourself.”

Whether it’s taking the time to read a book or be in nature, Longsdorf says it’s important to “be intentional about setting up that space for solitude, and claiming it and naming it as such.”

- Read the story: “How solitude is experienced in different ways,” Maine Public, Feb. 11, 2022

Dan Bliss ’85

“Fishing is not the focus” for friends reuniting on a Maine lake for 37th time — Bangor Daily News

With a weekend of fishing in February as an excuse, Dan Bliss ’85 and a group of friends have been meeting annually for the past 37 years, give or take a few on regular attendance.

The Bangor Daily News explains that the group started as a motley crew of Maine college students and longtime friends, but this self-described “founders club” now brings along other friends, family, and acquaintances. The original outing in 1985 didn’t result in any fish, but “we just had a blast,” Bliss told the newspaper, and a tradition was born.

They’re now in different careers, including education, banking, engineering, and boat building, but Bliss said the outing lets them take a break from their lives.

“This is something important that we need to hold onto and tell those stories and remember the times that we had together and what we did. Life is short.”

- Read the story: “‘Fishing is not the focus’ for friends reuniting on a Maine lake for 37th time,” Bangor Daily News, Feb. 19, 2022

Joe Hall, history faculty

Joe Hall: Wabanakis and the state can work together — the Sun Journal

A reform bill before the Maine Legislature would remove the sovereignty restrictions imposed on Maine’s four Wabanaki tribes in 1980 by settlement acts that left the tribes with fewer rights than all other federally recognized tribes in the U.S.

In an opinion piece for the Lewiston Sun Journal, Associate Professor of History Joe Hall suggests that affording the tribes more rights will strengthen current and future partnerships between the tribes and the state.

Hall points to the work of the Maine Wabanaki–State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission, created in 2013 to examine the harmful effects of state policies on Wabanaki families over the course of decades. The commission brought the tribes and the state — long distrustful of one another — together as equal partners in the process.

“Partnership is not easy, but as the work of the TRC shows, it is both possible and productive,” Hall writes.

- Read the story:

“Joe Hall: Wabanakis and the state can work together,” the Sun Journal, Feb. 13, 2022

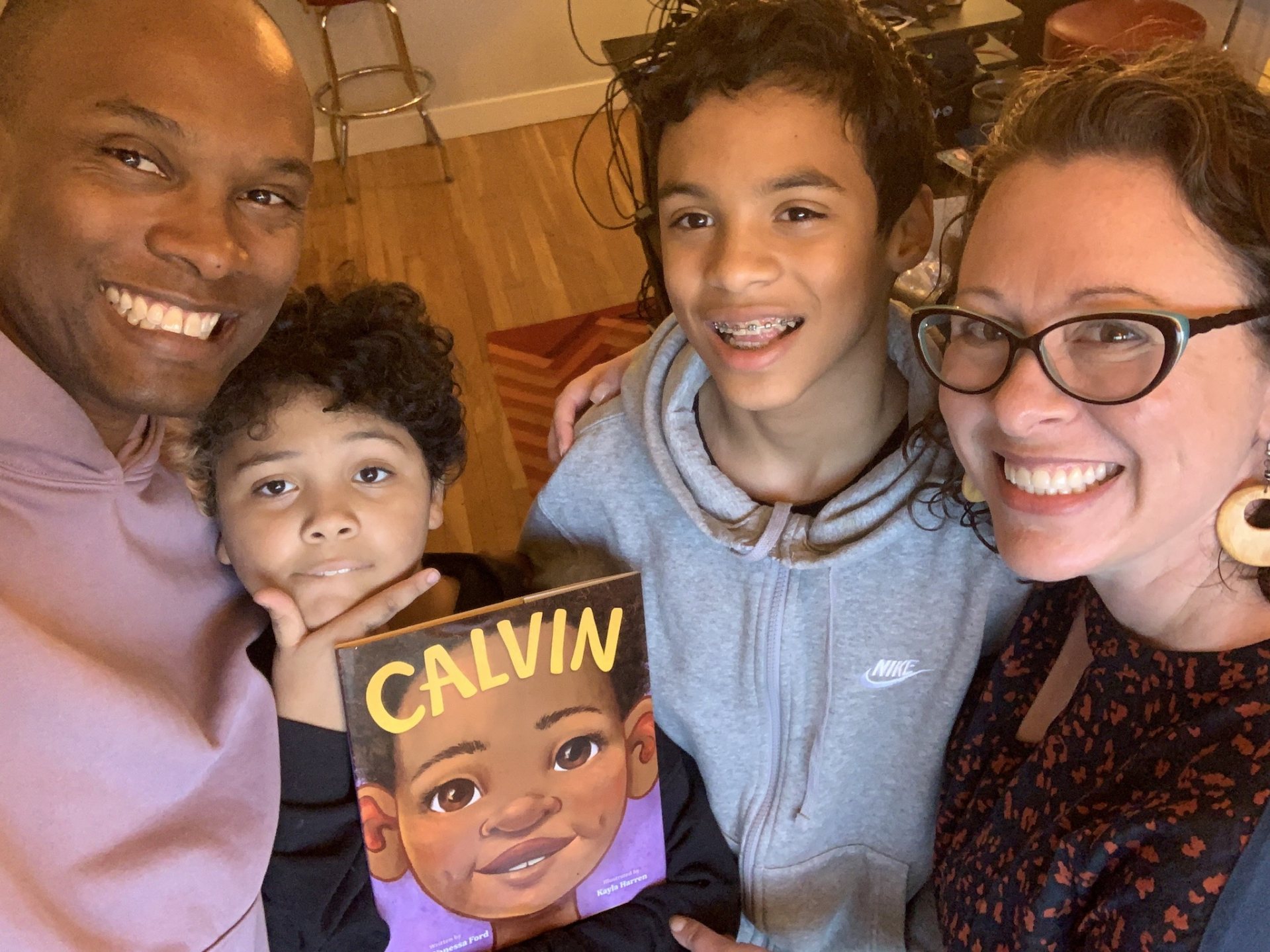

Vanessa Kalter-Long Ford ’02

Children’s book Calvin shows how a community can embrace a trans child’s identity — NPR

NPR’s All Things Considered interviewed Vanessa Kalter-Long Ford ’02 and her husband, J.R. Ford, about their co-authored children’s book, Calvin, which explores one child’s experience of coming out as transgender and was inspired by the Fords’ experiences parenting Ellie, who came out to them at the age of 4 in 2015.

For a child, the book can help provide the “language to describe how they feel or how they identify,” Vanessa told host Audie Cornish. “And sometimes having that language can be incredibly empowering.” It’s uplifting too: a child who can be their authentic self “draws in others around them,” Vanessa said.

As J.R. and Vanessa wrote in an essay for the Today show, “We wrote this book for kids like Calvin and Ellie, parents like us, and maybe just as importantly, the people around them: the grown-ups and kids learning to support the gender-expansive kids in their classes, on their teams, and in their neighborhoods.”

- Read the story: “Children’s book Calvin shows how a community can embrace a trans child’s identity,” All Things Considered, Nov. 9, 2021

Joshua Rubin, anthropology faculty

“A little different, a little broken”: How COVID-19 has changed us — Portland Press Herald

Marking the two-year anniversary of the first COVID-19 case in Maine, the Portland Press Herald’s Joe Lawlor interviewed Visiting Assistant Professor of Anthropology Joshua Rubin for a story about the effects of the pandemic since March 2020.

Loss of routine, loss of in-person interactions, and loss of loved ones are just some of the things the past two years have visited upon us, says Rubin. “It’s very difficult to reckon with the social and emotional toll of that kind of loss. Will America let people grieve?”

High school and college students have had to navigate a different world than they looked forward to. That has resulted in a different worldview, one that is “wary” and “sometimes fatalistic,” Rubin said.

“Two years of disrupted life will impact these kids in unknown ways for the next five years, or 20 years.”

- Read the story: “‘A little different, a little broken’: How COVID-19 has changed us,” Portland Press Herald, Mar. 6, 2022

Alexandria Onuoha ’20

Local activist calls for state action on missing Black women and girls — Boston Public Radio

Boston Public Radio sought out Alexandria Onuoha ’20 for a story about the racial disparities in the handling of missing-women cases by law enforcement, following the suspension of two Bridgeport, Conn., police officers for how they handled the death investigations of two Black women.

Compared with the cases of missing white females, the families and friends of missing Black women and girls often struggle to get the police to take their cases seriously, activists say. State inaction and poor data collection are twin issues, Onuoha tells Boston Public Radio.

“It’s unbelievable. Black women and girls, the organizers in Boston and in Massachusetts, are usually the ones that have to fight for our freedom, our liberation,” she said. “This is not a one-person issue. This is a collective issue.”

Harmful stereotypes exacerbate the problem. “Black girls are seen as hypersexual in a way that invites devaluation from others,” said Onuoha, who is director of political advocacy for Black Boston, a nonprofit focused on fighting injustice and creating community for Black Bostonians. “Black girls are not given the same care, the same grace.”

- Read the story: “Local activist calls for state action on missing Black women and girls,” Boston Public Radio, Feb 1, 2022

Meg Reynolds ’07

Book Review: A Comic Year, Meg Reynolds — Seven Days

Not many people deal with their post-breakup feelings by making a comic book, but that’s exactly what Meg Reynolds ’07 did, carefully cataloging the following year with prose and drawings, expressing her loneliness and sense of loss in a serious way.

Seven Days’ Jordan Adams writes that Reynolds’ book is, at times, “cheeky,” “deft,” and “expressive,” with the combination of prose poetry and pictures painting the clearest picture of the author’s thoughts.

- Read the story: “Book Review: A Comic Year, Meg Reynolds,” Seven Days, Jan. 12, 2022