For two days each semester, Assistant Professor of Economics Kyle Coombs’ “Data Science for Economists” students are laser-focused on one goal.

They hole away in a reserved space on campus for a 48-hour “hackathon” to test their problem-solving skills and apply code, economics, and data science to real-world issues in the local Lewiston community.

Coombs’ goals for the class are to teach students the skills needed for real-world project management and to tackle problems which harm society as a whole. Knowing how to work with data can be a great tool for justifying, evaluating, and addressing socioeconomic concerns.

“The motivation is around using data to get at social issues, inequality issues, and how it manifests around race, gender, income inequality, economic opportunity, and whether that’s equitable,” Coombs says.

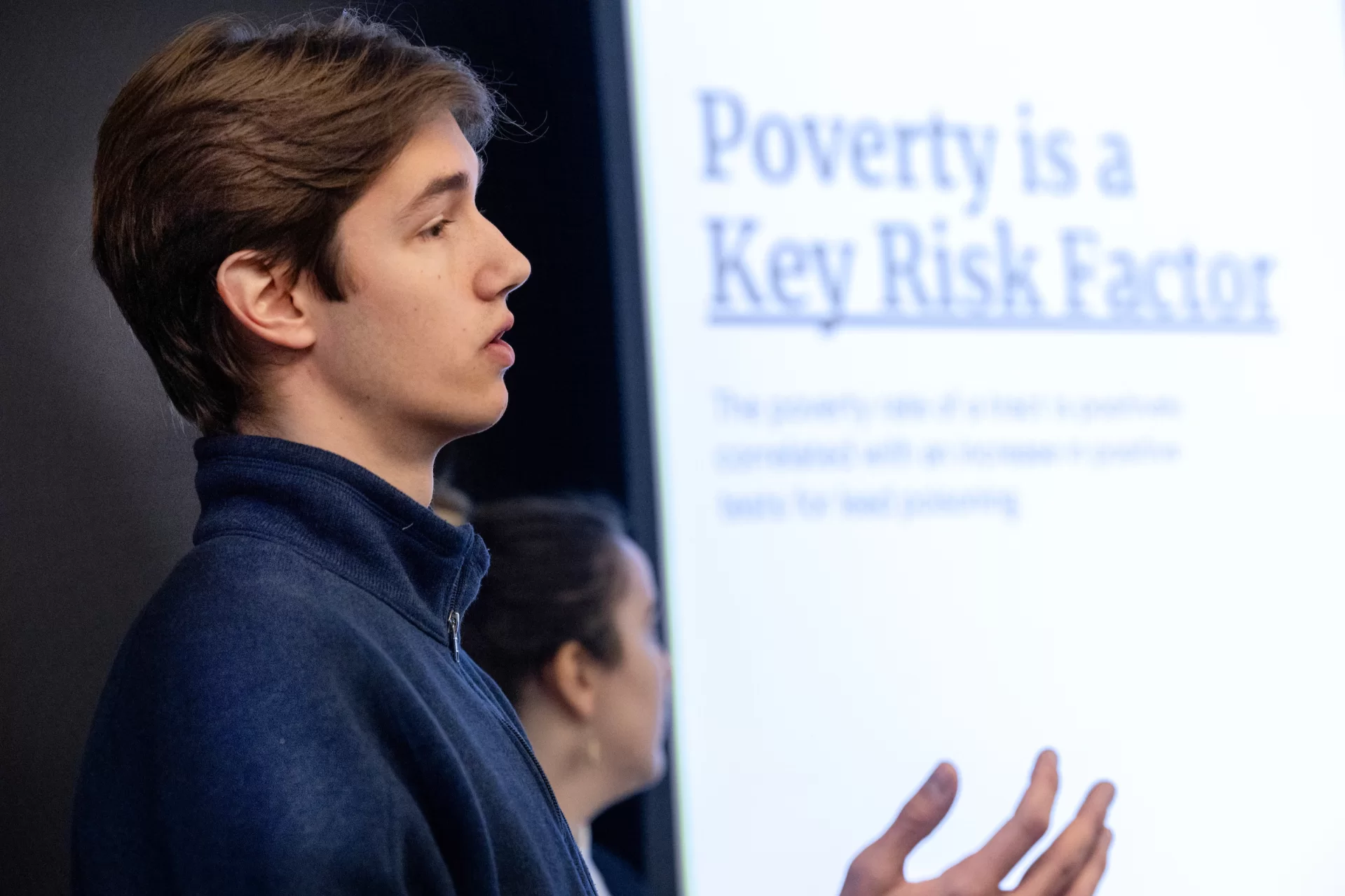

During the fall 2024 hackathon, Coombs’ students tackled a project to examine the efficacy of the city of Lewiston’s efforts to address lead-paint hazards. Like many other cities around the country with aging housing stock, Lewiston has faced problems of lead paint exposure and poisoning in the home.

The Lewiston–Auburn area’s rate of childhood lead poisoning incidents is the highest in the state, according to Healthy Androscoggin, a public health initiative focused on wellness and disease prevention in Androscoggin County.

“We’re the second largest city in Maine, and we have per capita the highest number of young people in the state,” says Jacqueline Crucet, a former city of Lewiston neighborhood development planner who has worked with Coombs and his students. “It’s very important that we have healthy homes for these young people to grow in.”

Through a partnership set up by the Harward Center for Community Partnerships, Coombs connected with Crucet, who provided the hackathon students with information about the city’s lead program.

The data included comparisons of lead paint prevalence with home age and socioeconomic indices, statistics about the kinds of homes that the city has targeted for lead mitigation programs, how the programs are implemented, whether through grant-subsidized or fee-based models.

Coombs’ students analyzed the data and found that the city’s efforts to reduce lead exposure are mostly meeting their goal of targeting homes with the greatest risk of lead exposure, suggesting that during upcoming efforts, the city focus its attention on homes built between 1920 and 1940.

Coombs’ other hackathons thus far have focused on the correlation between streetlights and decreased crime rates and designing rental assistance pilot programs to support local renters.

In recent years, the verb “hack” has shifted away from its nefarious meaning — anonymous computer geniuses working to steal data — to mean solving a problem or creating a shortcut. To wit, a hackathon is a fast-paced, collaborative gathering, with suitable high-tech overtones, to solve a problem in a short period of time.

The hackathons showcase the students’ emerging “creativity and technical skill,” Coombs says, “which is a lot of what you use in workplace scenarios.”

Each semester, Coombs collaborates with the Harward Center to reserve a campus space for the hackathon; there, students hunker down to work, though the “hackers” come and go for classes, sports, and sleep. While they hack, Coombs fields takeout requests and delivers favorites like Mother India and Pure Thai.

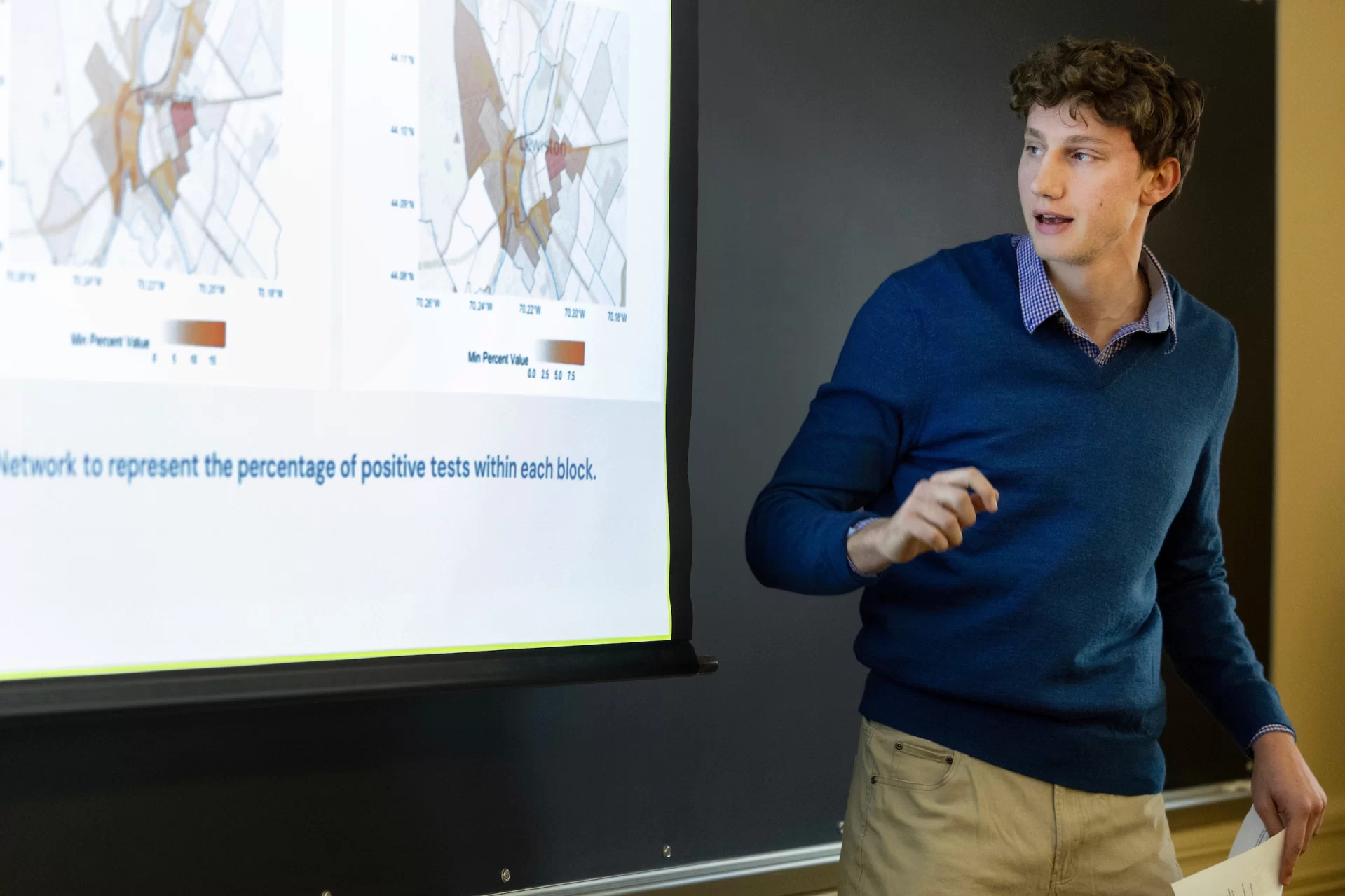

Nick Brown ’25 of Hopkinton, Mass., arrived at his hackathon last fall straight from track practice and settled in to work with a burrito in hand. He says he spent six to ten hours each day working on his team’s project.

“That was with fully comped, really good meals, and working with a great team of people,” Brown says. “It never felt at any point that I was not going to finish or felt rushed. It overall was a very positive experience.”

Like a team of coworkers, the students were responsible for independently dividing up group work and coordinating their schedules.

“I did a lot of the data cleaning and then the regressions, other people did a lot of visualizations or worked on the presentation itself,” Brown says. “It felt very natural, and we also felt like we were communicating very well.”

“Data Science for Economists” is cross-listed as both an economics and a digital and computational studies course. The hackathon is the culmination of a semester spent, for many of Coombs’ students, learning to code for the first time, an often-frustrating process of trial and error.

“You will make constant mistakes,” Coombs says. “It’s about learning how to get through the mistakes, push through, address the problems, help yourself find creative solutions to a technical problem.”

The students organize their work in GitHub, a software storage program, and code in the language “R,” which is free and open source, meaning any student can access the code from their personal computer. An economics and history major with a minor in math, Brown used the R skills he learned during the course to complete his senior economics thesis.

“In terms of raw skill building, this was probably the number one class I’ve taken at Bates,” Brown says.

After each two-day hackathon, the students present their work to city partners and make recommendations based on what they discovered. The city partners can then use the analyses in their own evaluations and projects.

“It was really cool to be able to present to community members and see them actually derive insights from what we found and think about how those could be used to actually benefit people,” Brown says. “That was really insightful for me, how you can leverage your skills to create meaningful impacts.”

Each hackathon subject ties directly into greater city plans. In 2020, Lewiston received a $1.3 million federal grant to develop a resident-led transformation plan, “Growing Our Tree Streets,” for its downtown neighborhood, which has nine goals that will be accomplished across 25 years. (“Tree streets” is the nickname of the neighborhood where many streets have names like Oak and Maple.)

Based on the strength of the transformation plan, the city was awarded a $30 million Choice Implementation Grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Lewiston is the first small city in the country to receive the competitive grant, which is intended to help cities revitalize and transform neighborhoods. “We are like this beautiful experiment,” Crucet says. “We’re the right size for this kind of major investment where we’re taking some risks and trying to be as innovative as possible to meet the goals that we’ve set out in the transformation plan.”

Crucet was attracted to Lewiston because of that very “go getter” mindset that led residents, including Bates alumni, to lead the charge for the transformation plan.

“We have this amazing cadre of Bates alumni,” Crucet says. “They’re doers and they’re taking all of their knowledge and all of their life experience and investing in Lewiston, and they see a future.”

By tackling subjects included in the city transformation plan and making suggestions to the city, Coombs’ students are able to join in on these real-world efforts.

“The exercise of the hackathon enables them to have the opportunity to inform actual policy and the business of the municipality in which they live,” Crucet says.