Staff at the Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library love giving walking tours of the campus. They function like walking Bates encyclopedias, dropping tidbits about everything from which building was the first one on Frye Street to which are the oldest trees on campus.

But the tours only happen a handful of times a year, and for Caitlin Lampman, the education and engagement archivist who works alongside Pat Webber, the college archivist, and Sam Howes, the reference and digital initiatives archivist, that had started to feel like too small a window to share all the knowledge they hold. “It felt like a lot to be just living within Sam and Pat and me,” Lampman said. “We wanted it to be more than just three walking tours a year. And we wanted to make it so people could access the information all the time.”

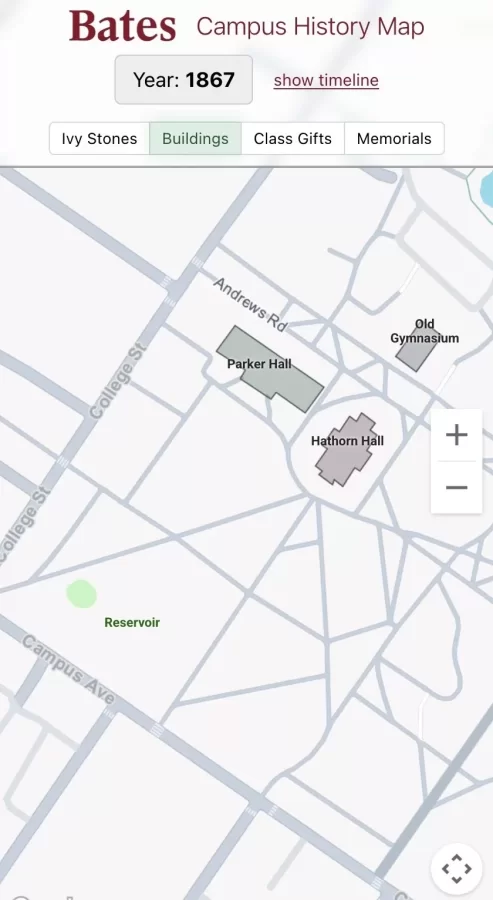

So Muskie Archives, which celebrated its 40th birthday last month, set out to build a time machine. Or rather, a digital time machine. Working with Jake Paris, senior web developer and designer, they stuffed all of that knowledge (plus GPS coordinates and archival photographs) into something that might not fly, but is transporting: a new digital map that provides users with an annotated snapshot of what Bates looked like at every stage of its 175-year history.

Layered and interactive, the map dates from the present back to 1855, when the college was founded. For now it’s available only if you’re on campus using Bates wi-fi (including if you’re on campus for Back to Bates this weekend) but by early 2026, it should be available from anywhere. Scroll through time and see what Bates looked like in 1878, when there were just a few lonely looking buildings in a lot of wide open space or 1940, when there were barracks housing student sailors for the Navy’s V-12 program.

For the time being, the map is only available to view if you are on Bates wi-fi (including the guest version), but during Back to Bates weekend you can visit the Muskie Archives to look at it from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. At some point in early 2026 the map will be viewable online from anywhere.

As is appropriate for a map that already shows hundreds of changes big and small to the Bates campus over 175 years — including the location of every Ivy stone — the new historical map is built for further evolution and flexibility. That flexibility is intended to accommodate the campus of the future, but also to account for all the nuggets of information the archivists expect to learn when the map becomes available to a wider audience. They’ve been uncovering new things about old Bates practically every day since the project got started. Take the plethora of tennis courts for instance.

“Step into my time machine,” said Sam Howes, typing away at his keyboard to pull up an early 20th century map of Bates. “There were tennis courts all over the place.” It’s not that Bates had huge tennis teams in the past; these were courts that offered recreational opportunities for all. They’d be displaced by new buildings, including Dana and Commons, and would be relocated. “I keep finding more in random spots,” Howes said.

“You do,” said Jake Paris, “Every week, it’s ‘I found another tennis court!‘”

To build the map, Paris used Google maps as the base and relied on a number of modern web app technologies, all very standard. “But the way the map is managed by the Archives office is unique, and intended to be very archivist friendly,” Paris said. “The team at Muskie can control the content simply by updating a Google Sheet and adding photos to a folder in Google Drive.” The app fetches the data from the sheet and then assembles it. “And at the same time, all the photos from the drive are downloaded and compiled into the app,” Paris explained.

Ideally, users will start suggesting and or submitting material to enrich it, because there are still some mysteries to Bates’ past. Take the Turner annex for instance, a building on Wood Street which was something between a carriage house and a garage. In 1988, for just one year, it was a residence, and Howes would like to know more about what it looked like.

“That’s the kind of thing where it would be nice if we could have someone who maybe lived there contribute some information,” Howes said. “They might even have a photo.”

One highly useful feature of the map is, when you click on a location — even something as small as an individual Ivy stone — you’ll be taken to historical, archival information, including vintage photographs of the building, feature or place.

Crowd-sourcing is one way to keep the historical map, like the campus itself, ever-evolving. And the archivists keep finding more layers they’d like to add. Lampman says historical trees, including trees planted by a particular class, or ones named in recognition of faculty members, will eventually be included. “We’re working on that,” she said.

Want to go old school? This Saturday Oct. 3 there are two opportunities for traditional campus tours led by the Muskie Archives. The first starts at 10 a.m. and will explore the early buildings on campus, the second starts at 2:30 p.m. and visits many historical trees on campus. Both tours start on the Hathorn steps.

The project took 18 months because of the level of detail — and accuracy — the archivists were going for. And they learned as they went. Take two trees between Ladd Library and Carnegie, a hemlock and a red oak. “We think they have been here the whole time,” Lampman said. The evidence? Photos from the 1880s and 1890s. “And for some reason, they have just never been cut down. They’re right between the two buildings.”

The trees are so wedged in between the two buildings, Lampman says, that it’s almost a surprise they survived construction. “We don’t know who made the choice to leave them there.” Other trees that haven’t survived, like the Stanton Elm, planted in honor of Johnny Stanton, professor of Greek and Latin, debate mentor and ornithologist, will eventually get a spot on the map. “We have a pretty good idea of where it was.”

“We think this map is a great product,” said Krystie Wilfong, who is associate college librarian for collections and scholarly communications and oversees the Muskie team. “It’s something that people can really interact with, from alumni and parents to local people from the community. It holds something.” Namely history, and the desire to share it.