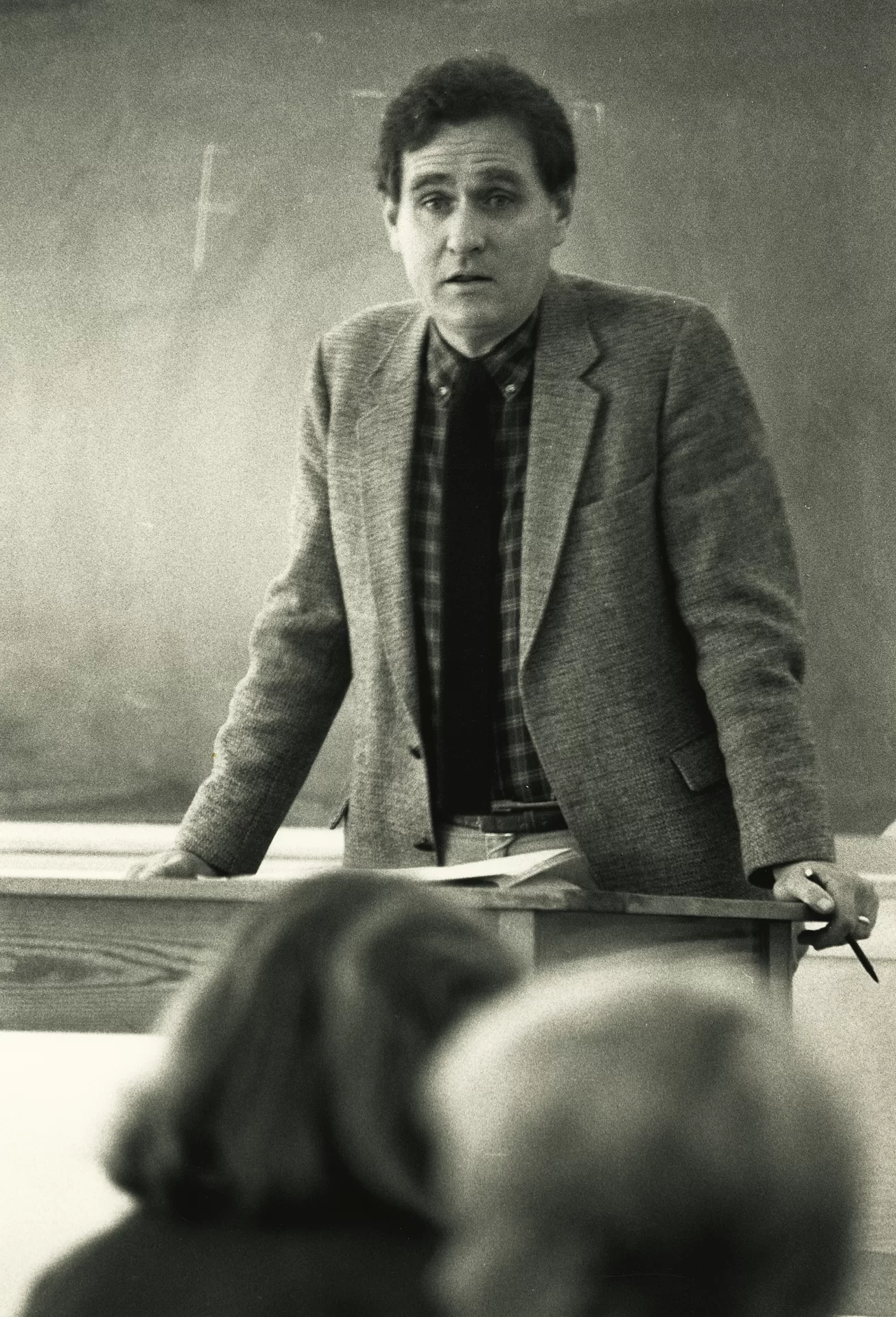

Charles A. Dana Professor Emeritus of Theater Martin E. Andrucki, a beloved and brilliant teacher and scholar who secured a seat at the liberal arts table for Bates theater, died Feb. 8, 2026, at age 80. A faculty member for 47 years, Andrucki was among the longest-serving Bates professors in the college’s history.

Raised in the Bronx, N.Y., Andrucki earned a bachelor’s degree in English, magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, from Columbia University and a doctoral degree in English from Harvard University.

Andrucki’s arrival at Bates for the 1974–75 academic year coincided with theater becoming a major for the first time. Yet the department, which at the time housed both theater and rhetoric, was at a low point due to retirements and departures. “It was on the verge of expiring,” recalled Andrucki in 2021. Some at the college were openly questioning the legitimacy of theater as a liberal arts discipline.

Martin Andrucki Service and Memorial Gifts

Martin Andrucki’s obituary includes information about his funeral service in Lewiston on Friday, Feb. 13; family and survivors; and a memorial gift designation to Bates. The service will be available via livestream.

As with other young professors who joined Bates in the 1970s and 1980s and helped to build academic programs, Andrucki arrived brimming with gusto; an early student described him as bringing “a fierce intellect and a wise-ass New York City sense of humor” to Bates.

The task before him 50 years ago, Andrucki recalled, was to “create a curriculum that emphasized literature and theory and producing serious drama on our stages. We wanted our majors to be broadly educated in theater and drama and to see theater as one of the liberal arts.”

During retirement events in 2021, proof of his success resounded in the words of theater alumni. Theater at Bates “equipped me with hands-on experiences I apply nearly every day in life,” recalled Bobbi Bell Birkemeier ’78. “Time management and making deadlines, thinking quickly on one’s feet, improvisation, how to take criticism and direction in a positive fashion, how to direct and delegate, and how to ‘play nicely with others’ in working collaboratively.”

And from his first days on campus, his students felt Andrucki’s intellect and generosity, his lofty standards coupled with a belief in their potential for success. “Marty was completely invested in our work in the classroom and onstage,” Sarah Pearson ’75 said in 2021. “Marty made me believe that anything was possible, and his confidence in me — in all of us — was invaluable and gave me the boost I needed to face the next stage of life.”

“He always seemed to focus on the big picture, the big idea, if you will. Plot. Character. Thought. Diction. Music and spectacle,” said James Lapan ’86. For Amanda San Roman ’17, Andrucki was a “steady and grounding force in my Bates experience. His subtle humor, wealth of intelligence, and supportive nature never went unnoticed by anyone he interacted with.”

Andrucki rose swiftly through the academic ranks. In 1975, he was promoted to assistant professor and that year began his decades-long service as department chair. He earned tenure in 1983, was promoted to full professor in 1990, and in 2001 was appointed to a Dana Professorship, one of the most prestigious faculty honors at Bates.

Though Bates theater was ripe for renewal in the mid-1970s, Andrucki was building on a firm foundation. Two years before his arrival, Bates had named its theater on College Street in honor of Lavinia Miriam Schaeffer, who retired in 1972 after leading the Bates theater program since 1938.

As Andrucki noted in 2021, Schaeffer was a champion of the Little Theater Movement that emerged in the early 1900s in the U.S., which emphasized authenticity over grandiosity, “aiming to produce challenging drama in an intimate atmosphere,” he said. The vibe always resonated with Andrucki. “Let’s remember Lavinia and those values as we move ahead,” he said in 2021.

At Bates, he taught courses on theater history, dramatic literature, directing, and playwriting. He directed more than 50 theatrical productions at Bates, in the U.S., and abroad. His directing ranged widely: classical and Shakespearean works such as Antigone, Hamlet, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream; European modern and political theater including Three Sisters, Endgame, and The Caucasian Chalk Circle; American and contemporary plays such as Bus Stop, The Skin of Our Teeth, Eurydice, and Love/Sick; as well as original and experimental projects including his own Marie and the Nutcracker and the radio-play production Radio Waves.

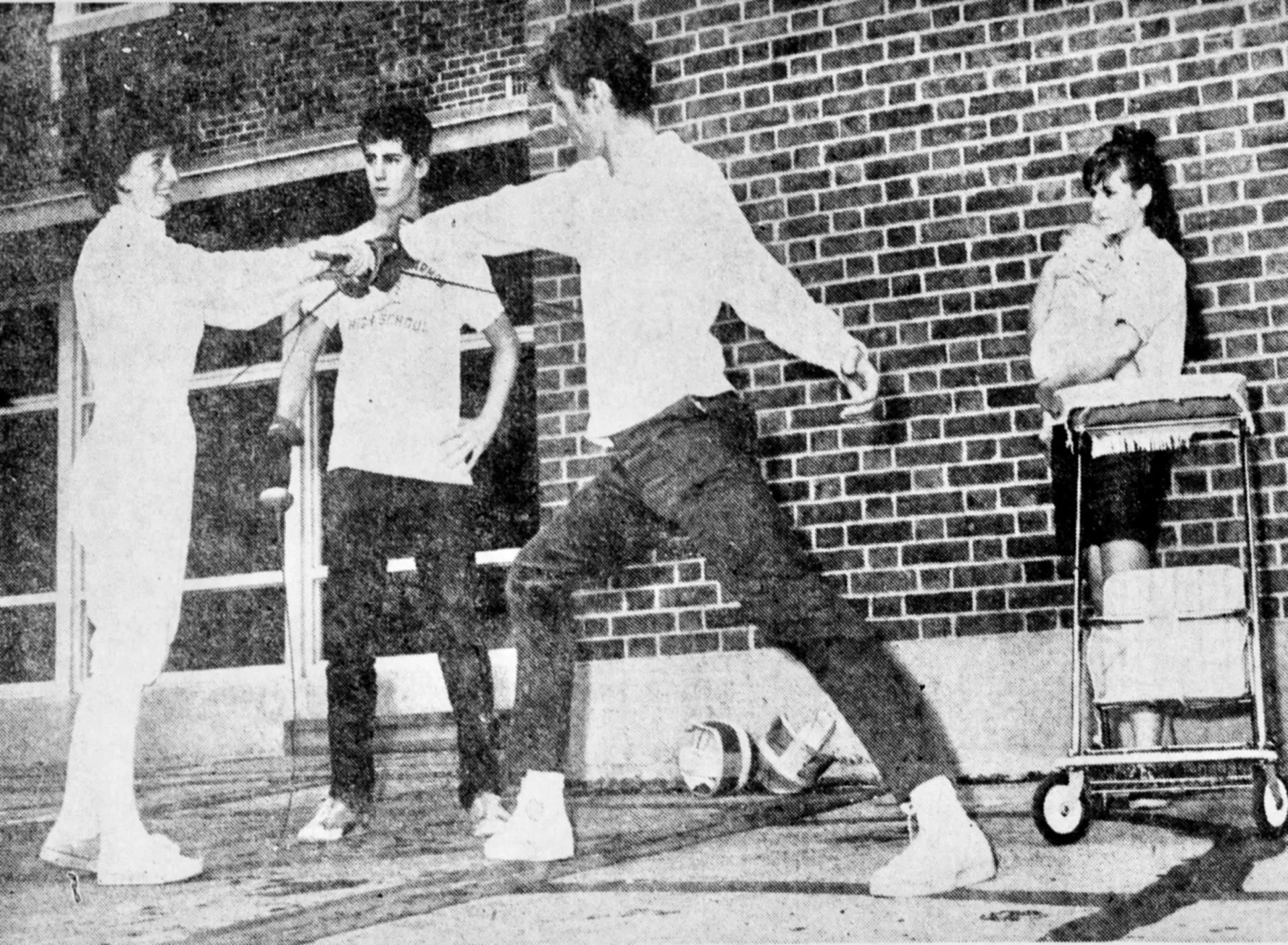

His can-do spirit inspired his students. In 1981, he scoured local junkyards to find the right prop for a production of Sam Shepard’s The Unseen Hand: a busted-up 1957 Ford sedan, hauled straight into the Schaeffer Theatre carpentry shop, where Andrucki chose to stage the avant-garde play.

Every other Short Term from 1999 to 2019, Andrucki and Kati Vecsey, senior lecturer in theater, led students to Budapest and Prague for the course “Central European Theater and Film,” the college’s longest-running off-campus Short Term program. “And yes, Marty learned to speak and read Hungarian,” said Vecsey, a Hungarian herself, noting the difficulty that English speakers have with the language.

“Marty and I watched many great, and many boring, theater productions together over the years,” Vecsey said. “When we would go to the theater, Marty always made sure to get an aisle seat, to make sure he had a quick way to escape if the show was unbearable.”

Learning Hungarian was just another example of Andrucki’s smarts, streetwise and otherwise. “There was this mysterious skill that fired his intellectual life,” Vecsey said, “a capacity to explore new territories without forgetting the old ones.” Andrucki brought “profound knowledge, wisdom, and humor into every room [he] entered, both as a director and as a professor,” said Maddy Shmalo ’19.

While he could be the smartest person in the room, Andrucki was often the most welcoming. “He seemed an untouchable mad genius to me at times, but at the same time a friend to sit and shoot the breeze with,” Chuck Richardson ’86 said during the 2021 retirement celebration.

A course with Andrucki, recalled writer Elizabeth Strout ’77 during a 2019 visit to campus, was not only one of her favorites, but also influenced her writing as a Pulitzer Prize-winning author of fiction. In the course, Andrucki guided his students through plays by classic American playwrights like Eugene O’Neill and Tennessee Williams. “He loved those people so much that I loved them,” Strout said.

From reading the plays, Strout learned a valuable lesson about writing authentic dialogue.

“When you write dialogue in a story or a novel, there has to be a translation between what people are actually saying to the page. You can’t write what people are actually saying, because it’s too boring. You’ve got to translate it to the page in a way that sounds authentic.”

In 1979, Andrucki was named a Mellon Fellow to conduct research into the teaching of theater. In 1987 he joined a directors’ forum at Columbia University, doing advanced studies with Liviu Ciulei, Lee Breuer, Adrian Hall, and others. He was a professor of English at the Harvard Summer School from 1993 to 1996. In 2002, he earned a Fulbright Scholar award for research in Hungary.

He wrote four plays, including Manny’s War. Staged at Bates in 2000 in collaboration with The Public Theatre of Lewiston, the play helped a local man, Murray Schwartz, reconcile his feelings of failure as a World War II soldier.

Schwartz, like Andrucki, was a New Yorker transplanted to Maine. He had headed to war with pride as an avenging Jew, and earned a Combat Infantry Badge, a Bronze Star, and three Purple Hearts, but then felt shame when, as a prisoner of war captured during the Battle of the Bulge, he resorted to stealing a fellow prisoner’s bread. “The play caught the inner struggle,” Schwartz said. “Not the generals’ strategies, but the betrayal of the will.”

As Andrucki wrote in Bates Magazine, the play’s opening night at Schaeffer Theatre saw Murray Schwartz “watching his wartime pain, psychological and physical, played out on stage. He was surrounded by family and friends, Bates people and Lewiston–Auburn citizens, a full house serving witness to a fellow American’s story.” The play was nominated for the New Play Award of the American Theatre Critics Association.

Andrucki was a prolific writer. He wrote a series of 15 critical essays published by the Portland Stage Company on topics ranging from love and lying in Sam Shepard’s Fool for Love to the handicap of virtue in Ted Tally’s Terra Nova. Among his hundreds of essays were 108 audience guides as a humanities scholar and dramaturge for two of Maine’s professional theaters, Portland Stage Company and The Public Theatre.

His writing appeared in Modern Philology, Theatre Journal, Text and Performance Quarterly, and The Columbia Encyclopedia of Modern Drama. In the early 1990s, he was host and writer of Wide Angle, a weekly television show on Maine Public focused on Maine filmmakers.

Not all his writing was theater-focused. In January 1981, he wrote a nostalgic essay recalling his childhood in the Bronx, and the memories of heating a home with coal, a fuel that made a resurgence during that historically cold winter. “It’s the childhood I really had,” he wrote. “For me, the rattling chute and dusty bin, the gritty ashcans and the pungent smell, are all redolent of New York in the last days of its unruffled pre-eminence, when televisions had round screens and no one had heard of the Sun Belt.”

Heating with coal in his Maine home created a connection with his son, Max, then 3 years old, the young boy being dazzled by the heat that poured forth from a pile of black rocks, “a moment of connection between my childhood and his, a New York memory for my son from Maine.”

When he retired in 2021, Andrucki had served Bates for 47 years, a tenure matched only by the late Karl Woodcock, professor of physics. To honor his career, the college’s black box theater was then named the Martin Andrucki Black Box Theater.

Andrucki treated theater, and his teaching of theater, as both an intellectual discipline and a lived experience. “I teach because I like working in a profession and at a place where intellectual and aesthetic values prevail, where telling the truth, as one understands it, is the objective,” he said, during a retirement event. Drawing on the thinking of the late Princeton scholar and poet Michael Goldman, he went on to explain theater’s power to deliver “total education.”

For students, that meant discovering their “entire being rather than the intellect alone.” Theater, Andrucki said, “engages the whole self,” whether as actor, director, designer, or playwright, in the deepest sense of education: the Latin educare, to lead forth, to draw out what is already present and waiting to be revealed. “Which is what college is supposed to be all about.”