There’s plenty to say during and about an event like Martin Luther King Jr. Day, a celebration that at Bates is so rich in revelations, recollections, and reminders.

Of course, it’s impossible to share all the great words we heard during MLK Day 2019 — but here are some that seem to sum up important messages from the day.

Far from Finished

The work to achieve greater equity within the Bates community, for all members of our community, is an ongoing process. While this and other stories of MLK Day 2019 show progress and community engagement, we are mindful that much work remains ahead.

“Why does it have to be one way or the other?” — Audience member, Benjamin Mays Debate

Featuring debaters from Bates and Morehouse College, the annual Benjamin Elijah Mays, Class of 1920, Debate offered this topic to the audience that packed the Olin Concert Hall: “This House believes that social justice movements should prioritize socioeconomic class over race and gender.”

When audience members were invited to ask questions, one man asked why it has to be one or the other.

Harry Meadows ’19 of Princeton Junction, N.J., suggested that debating the issue is less about choosing sides than helping people understand and refine arguments that, ultimately, will have an impact on real lives.

During the Benjamin Mays Debate, Harry Meadows ’19 listens as Zachary Manuel of Morehouse College offers a point of information. At right is Abby Westberry ’19. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“It would be great if the stakeholders of the world were able to properly balance these issues in the order that they were addressed,” Meadows said. “But I think the value of having a debate is to tease out the arguments that might expose issues with how we address the problem.”

“What can you do to acompañar? Smile.” — Sister Patricia Pora

Pora, a member of the Sisters of Mercy who works with Spanish-speaking immigrants in Maine, spoke during an afternoon panel featuring local and state advocates for immigrants.

Central to Pora’s work is the concept of acompañamiento — “walking with,” a theological term that emphasizes solidarity, vulnerability, and recognizing humanity.

In terms of deeds and actions, acompañar effectively means being welcoming, offering a “glad you’re here.”

“Accompany them to immigration check-ins or the Boston court, because there’s a lot of insecurity there,” Pora said. “Don’t play lawyer.” Instead, refer them to expert legal resources for immigrants.

“Advocacy with legislators is big,” Pora continued. “Study the history. There are many good books.”

And, “find friends on the journey.”

“We provide a little safety net and ways to maneuver in those settings when they’re not necessarily supported.” — Ellijah McLean ’20

During a morning presentation, McLean, Areohn Harrison ’20 of Rockville, Md., and Justice Prewitt ’20 of Memphis, Tenn., talked about mentoring middle-school boys at Hillview, an apartment community a couple miles from campus.

The mentoring program was sparked last year during an after-school program at Hillview, when boys started asking pointed questions about race, crime, and poverty.

In response, the three Bates students began a formal mentoring program, helping the boys tackle issues of racism and bias.

From left, Areohn Harrison ‘20, Obed Antonio, Reuben Mukenoli, Ellijah McLean ‘20 and Justice Prewitt ‘20 pose after their presentation about an aspirations program for boys at the Hillview apartment community. Teenagers Antonio and Mukenoli live at Hillview and are program participants. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

During the MLK Day session, they talked about biases they face at Bates and in Lewiston, the importance of connecting the two communities, and how mentorship benefits both mentor and mentee.

“There are not many faces at Bates that look like us,” said McLean, of Providence, R.I. The mentors take their personal experiences, along with academic courses, and “deliver the things we’re learning about to the guys we work with.

“The best way to do that is provide that welcoming feeling, that comfort that we have as black men that they don’t have at school.

“Talking to them about their teachers can be sad and heartbreaking, to hear about some of the experiences that they have that are very similar to ours, that we’re handling as 20-year-old men and that they’re trying to handle at 11, 12, 13 years old.”

“It was disguised as an effort of improvement.” — Stephanie Wade, assistant director of Writing at Bates

Wade was a coordinator of the workshop “How to Maintain Our Wild Tongues,” which asserted students’ rights to the dialects and non-English languages they were raised in.

The session’s title plays on the 1987 essay “How to Tame a Wild Tongue,” by the late scholar Gloria Anzaldúa, who described the English-only teaching practices she experienced growing up in Texas. “Wild tongues can’t be tamed, they can only be cut out,” she wrote.

Wade talked about the history of English-only teaching and monolingualism in America and how it was “disguised as improvement.”

“If you look back at the history of colonialism, you’ll find examples of missionaries and educators connecting the practice of taking the land with taking the language and the culture of the local people.”

“What does this informal structure mean when we’re talking about human rights violations?” — Carolina González Valencia, assistant professor of art and visual culture

González, a presenter during the panel discussion “#MeToo Means Who?” prefaced her segment about domestic workers by saying, “I’m a very proud daughter of a domestic worker.”

The panelists looked at forces that determine which victims of sexual violence get recognized.

Assistant professor of art and visual culture Carolina González Valencia was a presenter for the MLK Day 2019 session “#MeToo Means Who?” She’s shown here working with Lewiston High School students on a YWCA mural in 2017. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In the U.S., González pointed out, domestic work is often regarded as informal. “Employers don’t see themselves as employers, and employees don’t see themselves as employees.” That can have far-reaching ramifications.

“What does it mean if you experience some sort of discrimination or violence, and you don’t have an HR department to go to? You can actually go to jail, because it’s your voice against your employer’s, who is usually someone who has more weight.”

“Male domination of workplaces. Unequal protection of laws. Immigration status. No fellow employees. The informal nature of jobs. Language barriers. Fear of losing a job. Obviously, race. Mental state or ability. Class.” — Audience members during “#MeToo Means Who?”

During the session, the audience responded with myriad answers when asked, “What are the conditions that create vulnerability for targets of sexual violence?”

As attendees for the #MeToo session overflow the Hedge 106 classroom, presenters Melinda Plastas, Carolina González Valencia, Paula Espinosa ’19, Leslie Hill, and Emily Kane await the go-ahead to move to a bigger venue. In the end, the session moved to Pettigrew Hall. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I love the way they’re basically saying, ‘We believe you.’” — Emily Kane, professor of sociology

Kane, also part of the panel discussion “#MeToo Means Who?” commented on an open letter published last year by the Alianza Nacional de Campesinas (National Farmworkers Women’s Alliance) that expressed support for sexual-violence victims in the film industry.

The now-famous letter begins this way: “We write on behalf of the approximately 700,000 women who work in the agricultural fields and packing sheds across the United States.”

Said Kane, “I love the way they’re seizing a moral authority — that most of society doesn’t grant them — to say, ‘We can be people who get to tell you rich and famous women that we believe you.’”

There’s generosity there, Kane added, but also a sense that the farm workers know who they are. “It’s that sense that, ‘We know what this is about and we could help you figure out what to do — though also, you could help us.’”

“Your generation is producing the leadership that can carry such conversations forward and get beyond the headlines, get beyond the hashtags.” — Leslie Hill, associate professor of politics

Organizer of the panel discussion “#MeToo means Who?” Hill talked about the construction of activism, mentioning the Movement for Black Lives.

“They’re constructing a movement in the moment, taking on issues that are important inside their own communities and generating conversations about them,” said Hill.

Along the way, “they’re finding people to talk with and trying to figure out, ‘How can we change this future?’”

“I don’t necessarily know what to do.” — Wes Chaney, assistant professor of history

Cheney was part of a panel discussion by Bates historians about the intersection of activism and scholarship in the study of history.

A historian of China who concentrates on the environmental, social, and legal history of the Qing Empire (1644–1912), Cheney admits that he has “questions, and a difficult relationship with my responsibility to help change the present” in China.

“I am an outsider, but with family in China,” he explained. “I want to maintain my relationships with colleagues in China and not hurt them. I want to maintain my access to do my work. I can write about the past, but how should that animate my engagement with China today?”

Ultimately, he asked, “Is my responsibility only to the truth? That might help, but what if it also hurts family and friends and colleagues?”

“Have a personal plan for overcoming your fears. That’s how we make change.” — Trisha Kibugi ’21 of Nairobi, Kenya

Kibugi led a workshop that offered ways for people who want to be allies do a better job in the fight against oppression and for equity.

Toward the end, she and others talked about overcoming the trepidation that comes with taking any kind of new action, and the importance of having a plan.

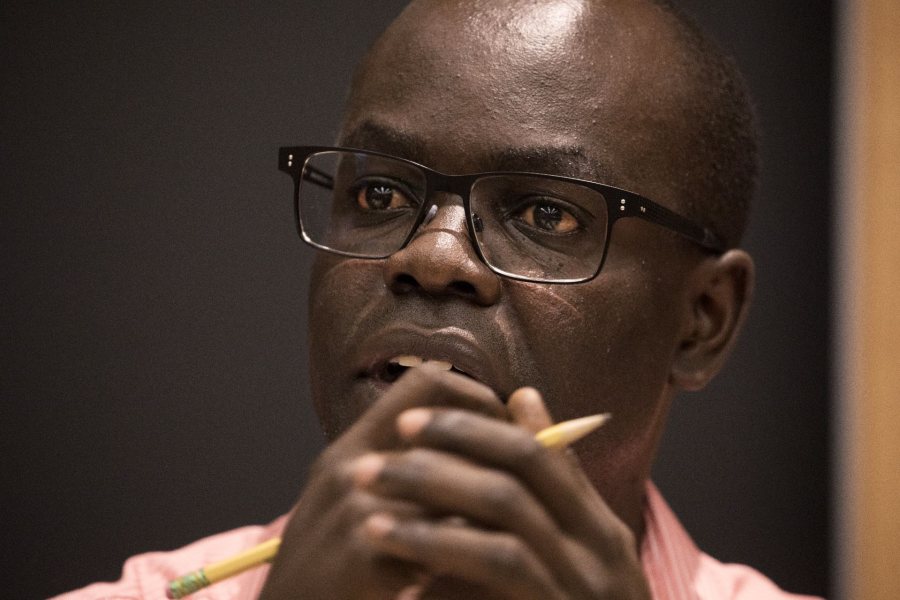

“In the field, the people who have suffered real violence tell a different story.” —Patrick Otim, assistant professor of history

Also part of the panel on activism and historical scholarship, Otim is a Ugandan native who was a journalist and then a communications manager for a relief organization before he became a historian.

In his work in war-torn northern Uganda in the mid-2000s, he noticed how scholars and others from afar would describe the the Lord’s Resistance Army and its leaders in highly critical terms, yet Otim would hear far different accounts from people on the ground who supported the LRA and who had suffered “real violence” at the hands of the Ugandan army.

Assistant Professor of History Patrick Otim was a presenter during the panel on activism and historical scholarship. Otis is seen in 2017 during a Bates faculty discussion after the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, Va. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Now, as a scholar looking at pre-colonial and colonial Uganda from 1850 to 1950, Otim has a similar on-the-ground approach as he examines oral histories from that time period in his research.

“Always listen to people,” he says. “And consider your sources.”

“It’s hard to put nuance on a protest sign.” — Alexis Baldacci, lecturer in history

In the panel featuring Bates historians talking about activism and scholarship, Baldacci noted that she thinks hard about where her scholarship “does or does not dovetail with activism.”

A historian of Latin America with a particular interest in Cuba and the Cold War period, Baldacci explains that “when you are thinking about complicated things in nuanced ways, it’s hard to boil that down” into a simple activist cause.

At the same time, her research in Cuba brings her into contact with contemporary activists, “who are doing really important work” and who also face “real political dangers” as they help Baldacci and other researchers by, among other cooperative acts, providing oral histories.

“So I use pseudonyms. I take precautions to make sure that when I leave Cuba, my impact will not be felt negatively by the people I left behind.”

In the end, she says, “I think my role as a historian is to learn from activists and to give them a platform when I can.”