A pair of iconic Bean boots. A bright yellow sou’wester. A bucket hat covered in colorful fly-fishing lures.

They aren’t your typical costume props for a Shakespearean play, but “they all belong in Maine,” says Carol Farrell, who is directing costume design for the forthcoming Bates production of Much Ado About Nothing, set in Bar Harbor, Maine, in 1945.

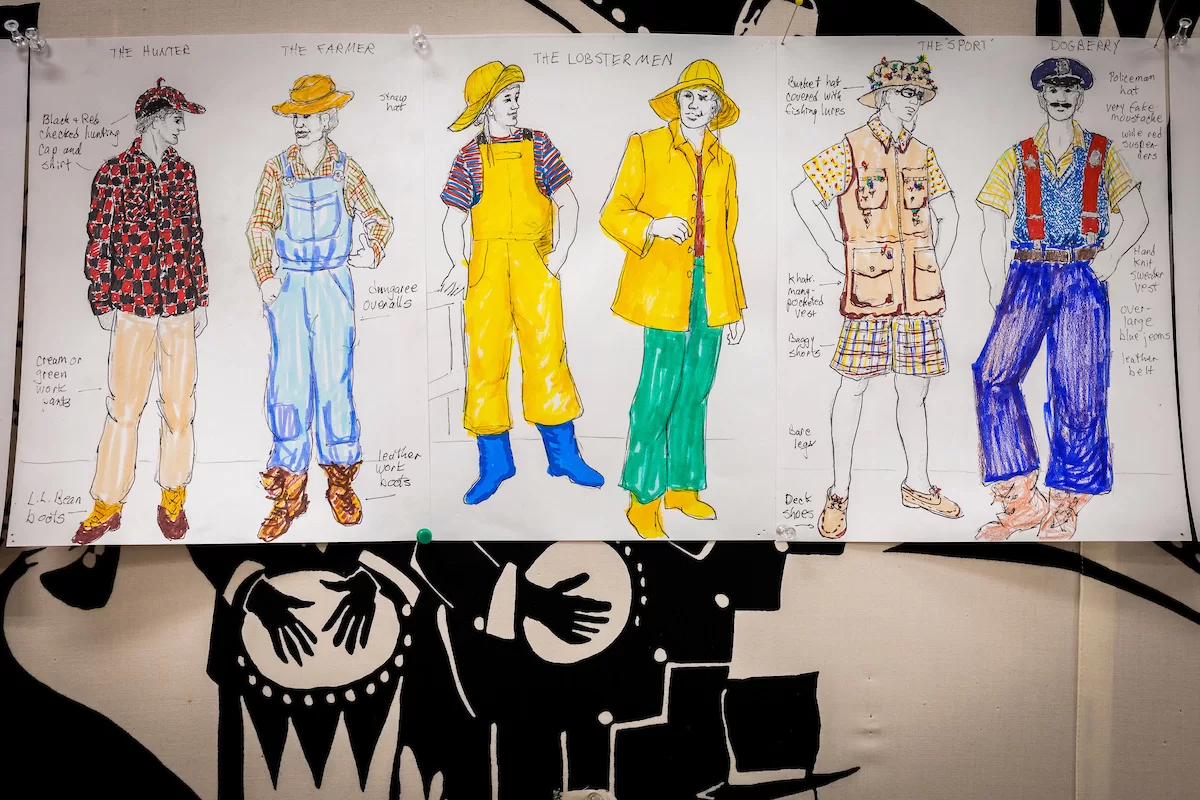

Tacked to one wall of the costume shop — next to a rack holding hundreds of colorful thread spools, are some of Farrell’s sketches of costumes, including Dogberry, a bumbling constable character, and several period archetypes of rural and coastal Maine: a hunter, a farmer, lobstermen, and a “sport.”

These characters, who comprise a kind of neighborhood watch in the play, are key to giving the play a Maine feel, says Farrell. In rural Maine, “especially at that time, people wore a lot of hats, literally. A lobsterman during the day might help the constable at night, that kind of thing.”

While a real 1945 Maine lobsterman might change clothes before his night job, in the play “there’s an internal logic to why these people are watchmen and they look this particular way. And it gives us a chance to play with being in Maine in a fun way.”

Among the watch, the only out-of-stater is the “sport,” a character that Farrell says harkens back to the early days of Maine tourism. “It was what the Maine Guides called the well-heeled people ‘from away’ who hired them. It was not a compliment, since the Guides had all the knowledge and did all of the work.”

He’s definitely “from away,” as they say, “up from Connecticut or Massachusetts or whatever, to experience the Maine wilderness,” Farrell explains. “The Maine Guides would paddle them around and they could do their fly fishing from the special little seat in the middle of the canoe that has a back to it — the ‘sport’ seat — and the sport was paddled around.”

The modern-day equivalent would be a tourist who is intent on getting the shot “for the ’Gram.”

So Farrell’s “sport” wears impractical white boat shoes, plaid Bermuda shorts, a fishing vest, bucket hat, and a short-sleeve, button-up shirt emblazoned with more fish than the old sport has ever caught by himself.

“No Mainer would be caught dead looking like this,” Farrell laughs. “But it’s what the out-of-stater thinks he ought to look like when he comes to Maine to be an outdoorsman.”

The fishing hat is a creative masterpiece in itself, festooned with mock fishing lures and flies, created by Adelle Welch ’25.

Among the 1,800 or so students at Bates, Welch might be the very best person to create a fishing cap. She grew up in Livingston, Mont., a small city along the Yellowstone River that’s home to the International Fly Fishing Federation museum, of all things.

As a child, she learned to tie flies from her grandfather. “I spent a lot of time with him in the summer on the river,” says Welch, recalling his fly-tying setup and “all the fun feathers and stuff. They looked so cool.”

All that experience helps her bring authentic details to the faux flies, such as adding “little eyes to mimic nymph flies, which are the ones that live at the bottom of the river.” Meanwhile, dry flies float on the top of the water. They’re more decorative, made with “feathers and stuff.”

Welch used a range of crafting supplies to create her flies, such as safety pins, string, fuzzy colored pipe cleaners, and ribbons — believable enough from a distance to catch an audience, hook, line, and sinker.