Shetland Islands Climate and Settlement Project

About three hundred years ago a rural farming community in the Shetland Islands, Britain’s northernmost group of islands, was overwhelmed by windblown sand. The environmental catastrophe was probably not the first time that sand from the nearby Quendale Beach caused problems for area farmers, but this time the sand blew far inland, and the community, called “Broo”, never recovered.

About three hundred years ago a rural farming community in the Shetland Islands, Britain’s northernmost group of islands, was overwhelmed by windblown sand. The environmental catastrophe was probably not the first time that sand from the nearby Quendale Beach caused problems for area farmers, but this time the sand blew far inland, and the community, called “Broo”, never recovered.

The international and interdisciplinary Shetland Islands Climate and Settlement Project is investigating the timing, potential causes, and results of the Broo catastrophe. Supported by a major grant from the US National Science Foundation, Division of Polar Programs, Arctic Social Sciences Program, the project links researchers in archaeology, history, geology, geochemistry, geophysics, biology, and digital mapping from four US and UK colleges and universities. In addition, the Project collaborates with Shetland educational and heritage organizations to incorporate local environmental and historical knowledge and to advance learning opportunities for visitors and residents alike.

Our Research Questions

The Timing of the Disaster

When exactly did the Broo disaster occur? When the project began it was known that the Broo Township had been destroyed by the mid-1700s (Irvine 1987). The Reverend George Low in a tour of Shetland in 1774 described the ruined township as an “Arabian desert in miniature”, with sand dunes partially covering the ruins of stone field walls and farm building foundations (Low 1879 (1774). Yet, a map from a prominent Dutch atlas from 1654 shows Broo as a major settlement in lands that are today a mass of grassed over dunes. Thus, pinpointing the beginning of the sand movements, and the dunes’ progress over time, are key objectives for the Project.

Causes

What caused the massive sand migration? The answer to this question is important today because coastal sands are dynamic environments where winds and surf can radically transform shorelines and inland areas over short periods of time. Historical examples of such radical change may hold lessons about the factors that affect these places, including how humans may increase the vulnerability of maritime landscapes to local and larger-scale environmental forces. We need to know more about the capacities for stability and change in these places both for understanding past human settlements on them and to anticipate the impacts of future threats to their modern uses and to their archaeological resources.

The Role of Climate Change

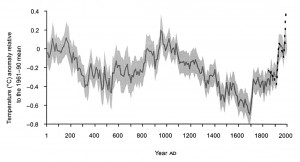

Could climate changes have played a role in the Broo catastrophe? H.H. Lamb, probably the most influential pioneer in the field of climate history research, proposed that major periods of coastal sand movements coincided with phases of rapid climatic cooling, and that the “Little Ice Age” of ca. 1300-1850 was the most intensive of these periods in the past two thousand years (Lamb 1977:129).

Northern Hemisphere mean temperature variations AD 1-1999, with two standard deviations in grey (Ljungqvist 2012: Fig. 3, 345).

Lamb believed that erosion damage from great storms (1991) combined with an exposure of shallow beach shorelines from dropping sea levels related to climatic cooling triggered huge amounts of sand to move inland. We now know that the general timing of the Broo catastrophe demonstrates that it occurred in some of the coldest decades of the Little Ice Age in Northern Britain, but this association does not mean that climate was the prime cause of the sand mobilization.

To better assess the role of climate change in the destabilization of the coastal environment the SICSP is more precisely dating the onset and progress of sand movements in the Quendale area, and is collecting proxy and direct historical evidence of the local climate when the township was destroyed. Other factors that may have contributed to the disaster include changes in farming practices or intensity and the introduction of rabbits, which were probably brought from Mainland Scotland in the 1400s or 1500s and which could have weakened grass vegetation through grazing and burrowing. We are learning information relevant to both factors by talking with long-time residents of the area who have grown up and worked around the the sand dune environment. Our local friends have finely detailed knowledge of the impacts of certain types of weather in different parts of the project area, and they are experienced in the sustainable use of the grassed-over “links” for sheep and cattle grazing. This knowledge is critical to reconstructing and interpreting the interplay of factors that led to the mobilizations of the sand landscape.

Social and Economic Responses

The SICSP is also researching the impacts of the sand catastrophe on the Broo farms, and it is studying how the 17th century tenant farmers and their landlords responded to the progressive destruction of their livelihoods and homes. We believe that the destruction of Broo was a “slow motion” catastrophe, in that the end result was a bit like Pompeii and Herculaneum – e.g. our archaeological sites are under up to two meters of sand – but the farms’ inhabitants most likely had months to possibly decades to develop economic strategies in response to the crisis: they had time to observe, think and experiment with different strategies to cope with the crisis.

The study of past geocatastrophes has become an important topic in archaeology and historical research (see Cooper & Sheets 2012). The information that comes from these studies of how social groups respond to various types of severe hazards, and make decisions on coping with or mitigating profound environmental threats may hold important lessons for developing the strategies of resilience needed for long-term economic and social sustainability in radically changing conditions. “Slow motion” geocatastrophes like the Broo example may become increasingly frequent features in a modern world experiencing global warming, although their immediate effects may not be as dramatic as disasters caused by “perfect storm” and “black swan” (Taleb 2010) events like superstorm tropical cyclones (Emanuel & Nin 2012).

Organization and Activities

US Participants

Amy Johnston ’12 and Professor Will Ambrose tag limpets for sclerochronological (growth ring) studies of climate effects on growth.

The Shetland Islands Climate and Settlement Project is innovative in attempting to see in fine detail what was most likely a complex, historical, environmental and human event. Thus, to achieve its goals the Project must study many kinds of diverse evidence, ranging from ancient documents to archaeological animal bones and buried sand strata dated through measuring the luminescence of silica with sophisticated geophysical methods. The overall project director and archaeological research coordinator is Gerald F. Bigelow, and the project is based at Bates College, in Lewiston, Maine, USA, where Bigelow works with these other project specialists:

| Michael E. Jones | Archival and Documents Analysis |

| Michael J. Retelle | Lake Core Sedimentology, Surficial geology and Climate Studies |

| Beverly Johnson | Geochemistry and Land Use Analysis |

| William G. Ambrose Jr. | Molluscan Sclerochronology and Climate Studies |

Additional collaborating institutions within the State of Maine include the University of Maine. Joseph T. Kelly and Alice Kelley, of the University of Maine Climate Change Institute are analyzing the movement of sand sand from Quendale Beach at different periods, and they utilize ground penetrating radar (GPR) to obtain information on geological patterns and buried archaeological sites and features.. The SICSP is also cooperating with the City University of New York, where Seth Brewington, of the CUNY Graduate Center, conducts zooarchaeological analyses of animal bone evidence from the archaeological excavations of Broo Sites I and II.

United Kingdom Participants

In the United Kingdom the project has partners in the Shetland Islands, in mainland Scotland, and in England. The Dunrossness Primary School has been involved in the SICSP since 2006, its students have visited the nearby Broo Sites excavations, and visiting project personnel in archaeology and zooarchaeology have given presentations for classes at the school, including talks at the school’s Global Consciousness & Sustainability Open Day in 2012.

The Project has also partnered with the South Mainland Community History Group for many years. The Group has been an important liaison with local landowners who have kindly given our research scientists access to their fields and pastures. The Group has also been an important link for setting up interviews with local residents for collecting traditional environmental knowledge (TEK) and and oral history. Project personnel have also worked closely on various aspects of research with staff from the Shetland Museum and Archives, and with the Shetland Amenity Trust, and we are grateful for their assistance and support.

The SICSP also includes partnerships with three research institutions on Mainland Scotland. Ian A. Simpson, of the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Stirling, is studying soils micromorphology and providing paleoenvironmental analyses. David S.C. Sanderson and Timothy Kinnaird from the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre at East Kilbride are conducting Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating of sands for geological and archaeological contexts. Andrew Dugmore, of the School of Geosciences at the University of Edinburgh has participated in the surficial geology studies of the project area, and is consulting on climate reconstruction. At the University of Bradford, the conservation of artifacts has been performed by the Conservation and Radiography Laboratory, and Robert M. Friel and Zoe Outram have produced archaeological maps of the Broo Sites and have conducted studies of plant remains from the sites.

Education

The SICSP has primary goals in learning as much as possible about the factors that led to the destruction of the Broo Township, but the process of that research also serves equally important goals in education and training. Primary school students, college and university undergraduate and graduate students, and local volunteers have worked on project activities and have attended outreach events. Thus far, seven successful undergraduate senior theses and two graduate theses have been written on project field and laboratory activities, and multiple papers and posters have been presented by students at meetings of professional organizations. Several undergraduate field courses have been taught at the Broo Sites excavations, and by the Fall of 2014 a total of 80 undergraduate and graduate students have been involved in SICSP activities. The SICSP’s contributions to regional environmental education were honored by an Environmental Award from the Shetland Amenity Trust in 2013.

Findings and Future Research

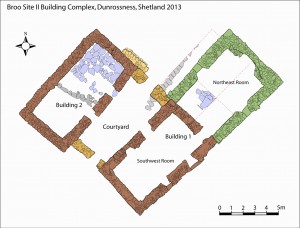

The large amount of data collected through three seasons of field research is currently being analyzed, and specialized research on various types of evidence will continue far into the future. At this point, it appears that the history of the destruction of the Broo Township was more complex than we originally thought. Sand deposition may have started around the Broo Sites as early as the mid-1500s, but the heavy sand blows that caused economic crisis began in the last two decades of the 1600s. Once the devastating sand deposition began, the farm may have been buried very quickly. Both documentary and and archaeological information confirm that the Broo Sites were completely abandoned by 1705, but not until the buildings were virtually entombed in sand. In the next three years we will begin a final phase of field research that will uncover the remainder of Broo Site II and a suspected agricultural building at Site I. In addition, more geological fieldwork will provide an enhanced and more detailed view of the progress of the sand movements inland.

References Cited

Blaue, W.J. & Blaue, J. 1654 Atlas of Scotland: Orcadum et Schetlandiae, Insularum Accuratissima Descriptio. Amsterdam.

Cooper, J. & Sheets, P. (eds) 2012 Surviving Sudden Environmental Change: Understanding Hazards, Mitigating Impacts, Avoiding Disasters. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Emanuel, K. & Lin, N. 2012 “Black Swan Tropical Cyclones.” Abstract NH23C-01 Presented at 2012 AGU Meeting, AGU, San Francisco, Calif. 3-7 Dec.

Irvine, J.W. 1987 The Dunrossness Story. Lerwick: A. Irvine Printing.

Lamb, H.H. 1977 Climate: Past, Present and Future. Vol.III. London: Methuen.

–1991 Historic Storms of the North Sea, British Isles and Northwest Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Low, Rev. G. & Anderson, J. 1879 (1774) A Tour through the Islands of Orkney and Schetland. Kirkwall.

Ljungqvist, F.C. 2010 A New Reconstruction of Temperature Variability in the Extra-Tropical Northern Hemisphere during the Last Two Millennia. Geografiska Annaler 92 (Series A, Physical Geography):339-351.

Taleb, N.N. 2007 The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. London: Penguin.

Thanks

In addition to all of the individuals and organizations mentioned so far the SICSP would like to thank the following groups, organizations and businesses for various forms of support to the Project:

Robert E. Proctor

Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) Shetland

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) Shetland

NAFC Marine Centre, University of the Highlands and Islands

University of Bradford, Archaeological Sciences

Net Services (Shetland) Ltd