Cambodia Memoir

I can’t believe you abandoned us,” said Kanya Duong, her eyes welling with tears. “Abandoned you!?” I stammered. The quick exchange silenced everyone at the dinner table. It was the summer of 2000, and Kanya had brought her husband and children to meet my family.

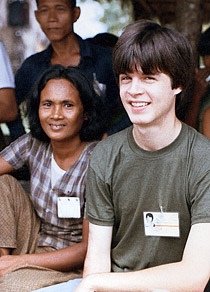

Scott Allen ’84 and Kanya Duong. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen.

“Yes, you abandoned us,” she said again, her anger growing. “One day, you just left the camp. Everyone said, ‘Don’t worry. Scott will get us out.’ But you didn’t. We were supposed to be resettled in Connecticut with you, not California to live with an uncle.”

My mind flew back 20 years, to 1980. I saw myself, a mentally restless high school senior in a contented suburban Connecticut town. I had physically healed from an accident, several years before — being burned over 35 percent of my body, including my face and hands. But that incident, in some profound way, left me vulnerable to the horrific images and stories coming from the killing fields of Cambodia. So vulnerable and consumed, in fact, that in March 1980, at the age of 17, I took off on a solo journey to Thailand to serve the refugee cause.

More memories rushed back. Meeting Kanya, my own age, in one of the refugee camps; her widowed mother, Thida Duong; and Thida’s six other children. Feeling an all-consuming obsession to get them to America — even convincing my parents to sponsor the Duong family. In the end, I fully believed that I had succeeded. They came to America.

Then my mind backflipped to the present, to my life as a physician, husband, and father who looks back on that experience and achievement in 1980 as the foundation of my identity as a healer and helper. But Kanya’s arrival back into my life, and her harsh accusation, had blurred the picture. That night, in my own dining room, I struggled to convince her that there was more to our story.

March 1980: Mairut Camp

Teenager Scott Allen, having secured work at Mairut shortly after arriving in Thailand in 1980, sits with a group of Cambodian refugees in a bamboo hut characteristic of the camp. Teenager Scott Allen, having secured work at Mairut shortly after arriving in Thailand in 1980, sits with a group of Cambodian refugees in a bamboo hut characteristic of the camp. |

It was chance that brought Kanya and me together. As I walked between two rows of bamboo barracks at Mairut, a Cambodian refugee camp nestled on the southern end of the Thai border, an odd site caught my eye. There, at the end of one of the barracks, sticking out of the sand, about 8 inches high, was a plastic sign with the familiar golden arches of McDonald’s.

“You like my sign?” asked a smiling man in a white shirt, jeans, and thong sandals. “Welcome to Mairut Camp. My name is Ly. I’m very happy to meet you.” I shook his hand and introduced myself. I laughed and said, “Yes. Do you know what that sign is?”

“I am not sure — it came with toys they sent for the children. I put it there for fun,” he said. “Come. Would you like to look around? I can interpret for you.” Ly, a Chinese-Khmer, had had two years of college education in Cambodia before Pol Pot came to power.

We waded into the crowd that had formed in the first minutes of my arrival, and walked to his hut, Building 19, where I met his wife, Kolap. A few minutes later, a woman who had been sitting nearby grabbed my hand assertively and pulled me over to sit down next to her. Ly smiled reassuringly. “This is Thida, our friend. She is alone with her seven children,” he said. “She wants you to help her with her English.” Despite the boldness of her move, Thida kept her eyes on a book, never once looking me in the eye, emphatically moving her fingers across the pages of a ragged English primer. She tapped at the book. I recited: “That says, ‘I will go to the store on Saturday.’”

“I-will-go-to-the-store-on-Sa-tur-day,” she repeated.

I became friends with Ly, Kolap, and Thida. Though widowed with seven children, Thida carried the weight of her world with grace and optimism. She smiled often and loved to joke and tease. She eagerly conversed with me through Ly and helped me practice my Khmer, laughing frequently at my awkward pronunciations. She was eager to develop a friendship, and I could not resist her charm and spirit. When I sat beside her, I felt peace — indeed, her name means “angel” in Cambodian.

Kanya, the eldest child, was different. She was my age, and naturally I tried to win her attention. I tried to joke with her, but she would turn away or run away. Rarely, I would get her to smile. A brief smile, a blush, and she’d be gone. She was ever present yet ever silent, small and thin with a soft complexion and brown, shoulder-length hair that fell around her neck and face as she looked down. She moved soundlessly about the bamboo hut, crouching to wash a dish, tending to her younger siblings, quietly studying in an English primer.

Ly, Kolap, Thida, and I savored our new friendship. They found my friendship a hopeful tie to the outside world; through them, I began to comprehend the spirit of survival amid loss and suffering. We reveled in the moment, and we laughed and sang often, listening to cassette tapes of Western music that had been popular in Cambodia before the war. I would strum the barely tunable guitar circulating about the camp, and they would request songs. They loved the Bee Gees’ “I started a joke, which started the whole world crying….”

It was, in fact, a simple joke that would insinuate itself as truth into my relationship with the Duong family, a joke that later led to Kanya’s bitter sense of betrayal.

Noticing how Cambodian families would give family titles to close friends, I asked Ly how I should refer to Thida. With a serious face he said, “You should call Thida ‘Madai k’mai kyum Thida.’” When Thida returned to the barracks, Ly nodded at me, and I greeted her in my clearest Khmer. Thida looked shocked, then laughed. Ly curled over in deep laughter, then brought me in on the joke. I had just said, “Greetings, my mother-in-law Thida.” From that point on, I referred to Thida as “Madai k’mai,” and I was adopted as the “son-in-law.” It was a good joke, and we all needed to laugh.

One Saturday night, I missed the ride back to the nearby hotel where the relief workers stayed, so I spent the night in the camp. When it came time to take an evening bath, I changed into a borrowed khrama — the Cambodian word for a male-worn sarong — and went over to the well. As I started pouring water over myself, a crowd gathered to watch the young Westerner’s first attempt to bathe in a khrama. The crowd growing, I tried to complete the job as quickly as possible. Ly laughed and said, “You know, in Cambodia we say a young man is not ready to marry if he does not know how to wash his body everywhere.” I hadn’t washed my privates, worrying that I’d drop my meager coverings altogether. But Ly had challenged my maturity, so I quickly washed and rinsed myself, to the howls and hoots of laughter. As I stood wrapped only in a wet khrama in the fading light of the camp, I felt all eyes upon me, including Kanya’s. Along with her siblings, she was laughing — a rare sight.

Winter 1981: Bates College

My relief organization, the Catholic Office for Emergency Relief to Refugees, ran out of funding over the summer. After a stint working at the U.S. Embassy, I was exhausted emotionally. It was time to leave Thailand. All summer, I had fruitlessly tried to get Thida out of Mairut Camp. In one last attempt, an embassy colleague, Jeff Sandel, was at least able to improve her asylum category.

I entered Bates in January, and day to day I did the course work yet was overcome with guilt. Despite Jeff’s help, Thida and her family were still languishing in Mairut; our friends Ly and his wife, Kolap, had long since received asylum in Canada. Thida, according to her increasingly desperate letters to me at Bates, faced possible forced repatriation back into Cambodia. I felt impotent and powerless, and I hated the feeling.

One positive act was when Dean Carig-nan agreed to forward a letter requesting help to Edmund Muskie ’36, who had just served as President Carter’s secretary of state. A few weeks later, I was in the dean’s office in Lane Hall when the phone rang. “I have Senator Muskie’s office on the line,” I heard Edna Bunker say. “They’d like to know how to get a hold of Scott Allen.” So I took the call right there. A Muskie staffer, Carol Parmalee, told me they wanted to help, and I said that the only thing I wanted was a letter of inquiry from Muskie. “Is that all? Are you sure that’s enough?” she asked. She suggested that I draft it. “Write it as if it were written by the senator, and I’ll put it on his letterhead and have him sign it.” She finished by saying, “Now let me be frank. We really are willing to do whatever we can to help.” Jesus, I thought, how’s that for service?

A few months later, on Sept. 25, 1981, Thida and her children finally arrived in Long Beach, California, rather than in Connecticut, where my family and I had agreed to sponsor her. (History may never show whether Muskie’s letter hastened the process.) I was surprised they were in California; apparently Thida had located her late husband’s brother in California, and regulations required her to settle with a family sponsor. She was safe, and I was relieved. I looked forward to the day we might meet again.

Summer 2000

The impotence and guilt I felt around my first journey into the real world hounded me through the years that followed. I returned to Thailand for three additional, and more productive, tours of duty with the embassy. After seven years of medical training, I embarked on a career in international medicine. Later, the lessons I learned from Thida — how to face dream-shattering changes with grace — allowed me accept the fact that my child, born with severe physical and neurological problems, would end my traveling.

By summer 2000, I was in Rhode Island working in private practice and for the state Department of Corrections, the closest thing to the challenge of my earlier medical work in the developing world. One day, my mother gave me the letters that I had written from Thailand in 1980. Reading them rekindled the dormant passion of those weeks of friendship, and having fallen out of touch with my Cambodian friends, I decided to invite Kanya, who lived in Massachusetts with her husband, Narin, and their three children, to dinner to meet my wife and son.

That was the evening Kanya accused me of abandoning her family. At the end of the evening, after I had shared my story, she and I spoke alone. There, with many pauses and hesitation, for the first time in her life with another person, she turned the light on her darkest memories. As a girl in Cambodia, she had been repeatedly abused. She withdrew from everyone and stopped going to school. She stopped dancing, too, which she loved, because she loathed attracting attention to herself. She never told anyone. She said, “I was going to tell my dad before he died,” of starvation, under the Khmer Rouge. “But then I said this was not a good thing to tell him before he died. It would only make him sad.” In the camps, she and her sisters drew unwanted attention from men who knew the vulnerability of a fatherless family. “When I met you — do you now understand why I was afraid of men?” she asked. “Over time, I realized that you were different than other men. You never looked at me the way other men did. I wrote in my journal that I would want to marry a man like you. My friends started to talk to me. They said, ‘Scott is sponsoring your family. He already calls your mom mother-in-law.’

“Then, one day you were gone. My mom said she found my uncle living in California, and we had to go there. In the end, I decided you abandoned us.” Thida never told her eldest daughter the full story because that’s how the widow led the family after her husband’s death. “Mom became more like the traditional Cambodian man,” Kanya said. “She would make plans for our family, and she would not always discuss them with us. She would simply tell us what to do.”

Back in 1980, Thida, Ly, Kolap, and others began to heal in the kinship of fellow survivors. But Kanya was not yet ready. Years later, it should not have surprised me to be Kanya’s lightning rod. One day after our reunion, as she still struggled with unearthed memories, Kanya recalled her father’s advice to her mother: Keep the family together, no matter what. “I told my mother the other night that I didn’t know if I should still talk to you,” Kanya told me. “She told me, ‘Scott is like family. You must keep the family together. That is how you survive.’”

In 2004, Thida Duong, the Duong family matriarch, died of a stroke. She was 58. Scott Allen lives in Cumberland, R.I., with his wife, Emma Simmons, son Miles, 12, and daughter Kari, born in 2001.