Six questions with Professor Alexandre Dauge-Roth on the 20th anniversary of the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda

April marks the 20th anniversary of this genocide in Rwanda, three months of violence in which Hutu extremists killed as many as 1 million Tutsi and moderate Hutus.

Alexandre Dauge-Roth, associate professor of French and Francophone studies, is an expert in the literary, cinematic and testimonial representations of the 1994 genocide.

Bates students visit the Murabi Genocide Memorial site in 2009 as part of Alex Dauge-Roth’s Short Term course “Learning with Orphans of the Rwandan Genocide.” The sign refers to the French soldiers who created a volleyball pitch amidst mass graves during their occupation in June 1994. More than 50,000 people were massacred at the site.

He was invited to take part in two commemorative events last week organized by Bene-Rwanda, the Rwandan diaspora association in Italy. The events were part of “Kwibuka 20” — “We need to remember” — a commemoration based in the Rwandan capital of Kigali with satellite events around the world.

Dauge-Roth explains the events of 1994 and what is at stake for Rwanda moving forward.

1. What was the immediate impact of the genocide on life in Rwanda?

The genocide killed more than two-thirds of the Tutsi living in Rwanda, close to 20 percent of the entire population and saw another 20 percent flee to the current Republic Democratic of Congo. In July 1994, the country was a field of ruins and chaos: No institutions had been spared. Suspicion and hatred prevailed among the two major segments of the population. Grief and trauma were palpable in everyone. The social cohesion of the country was in pieces, and everything had to be rebuilt from zero.

2. How did Rwanda move on after that?

The first priorities were national security, the rebuilding of the institutions, establishing peace in order to attract investments — and, of course, finding a way to implement justice to try the hundreds of thousands of people suspected to have taken part in the genocide.

The ethnic labels “Tutsi,” “Hutu” and “Twa” were banned from official government documents, and a nationalistic discourse arose to transcend ethnic divisions.

Moving quickly away from a punitive conception of justice to a form of transitional or restorative justice, the Rwandan government established in 2001 the gacaca courts. These courts heard 1.4 million cases in a span of 10 years.

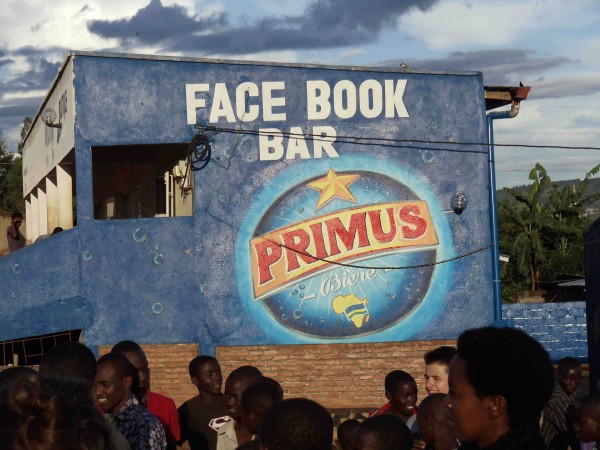

Bates students interact with local youth outside a bar in Nyamata during a visit in May 2013. For Dauge-Roth, the photo “signifies the global connectedness of Rwanda, where 60 percent of of the population has a cell phone and every young person has a Facebook page.”

3. How successful have these efforts been?

Needless to say, not everything has been achieved and nothing is perfect in Rwanda today — as is the case in any country, African or not. The current president, Paul Kagame, must step down in three years at the end of his second term. It remains to be seen if Rwanda’s institutions and the social fabric of the country will be strong enough to ensure a peaceful political transition.

Among the challenges are Rwanda’s distribution of wealth and demographic trends: The population has doubled in 20 years, and land and resources are scarce.

In the long term, though, the biggest issue will be to see how the generation born after the genocide — more than 50 percent of the current population — will embrace the newly coined national identity and whether they refuse to revive ethnic categories and hatred for political gain.

4. Tell us about your involvement with the commemoration events in Italy.

My talk in Rome focused on the numerous political and personal challenges survivors face when voicing their experiences. Their testimonies are an attempt to gain social recognition for their past sufferings and present needs.

In addition to a roundtable on the tensions between personal and collective memory in post-genocide Rwanda, I also led a pedagogical workshop in Genoa, where I presented the value of learning with survivors of the genocide against the Tutsi when teaching courses on this genocide and the current national reunification process.

5. What other projects on Rwanda do you have planned?

With French colleagues, I am organizing a three-day international conference and a film cycle in Paris this November themed “Rwanda 1994–2014: Memory Constructs and the Writing of History Twenty Years After the Genocide.”

My current book project, Who Speaks Behind the Archive? Personal and National Reconciliation in Rwanda, focuses on the cinematic and documentary representations of the reconciliation process in Rwanda.

6. Are you planning to teach your travel Short Term “Learning with Orphans of the Genocide in Rwanda” in the near future?

I plan to go back with students in 2016, before Rwanda’s presidential elections in 2017.

In the meantime, I will teach a new version of the course “Documenting the Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda” this fall, with a special focus on how the current politics of national reunification and the gacaca transitional justice have shaped representations of the genocide.