Bates in the News: Feb. 13, 2015

John Tooker ’92

When bugs don’t eat slugs, there’s a problem afoot

A Newsweek story cites research by insect ecologist John Tooker ’92 to explain why slugs have become a big problem on soybean farms.

Tooker has co-authored a study that has found a reason. An insecticide intended to kill seed-eating bugs is getting into the food chain and killing the predatory beetles that eat slugs.

Thus uneaten and thus unchecked, slugs are tearing into soybean crops.

A slug munches on a soybean seedling. (Nick Sloff/Penn State)

A Newsweek story in January focuses on Tooker’s research, which was published in the Journal of Applied Ecology.

The insecticides are neonicotinoids (they’ve also been linked to the die-offs of honeybees). Newsweek says that so-called neonics are used on “about half of America’s soybean seeds and 95 percent of corn seeds, the two biggest cash crops for commercial farms in the country.”

Turns out that slugs can consume neonics and survive. The poison remains in the slugs’ system, which kills or poisons the ground beetles that would eat them.

And here’s an irony: There’s evidence that neonics aren’t even needed. The EPA said last year that neonics provide “little or no overall benefits” and Tooker told Newsweek that “one of my main concerns with neonics is that they’ve been used regardless of need.”

From the scholarly article:

[T]his indiscriminate use can have unintended consequences, with measurable costs for farmers. Using neonicotinoids only when and where they are needed, guided by a strong understanding of the underlying ecology, provides potential to harness their strengths and limit their weaknesses to achieve more sustainable pest control.

An associate professor of entomology at the Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences, Tooker was a biology major at Bates.

His adviser, Sharon Kinsman, “gave me a start in plant-based research,” he says. (Plant-based research also helped Tooker meet his future wife, Megan Weaver ’92, as they did research together, looking at burrs and cockleburs, at Bates-Morse Mountain. “We actually got together after the project was done,” John says, “but spending all that time together did not hurt!”)

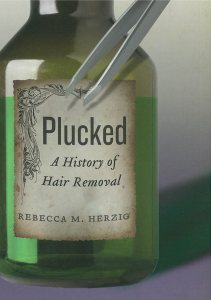

Rebecca Herzig

The race to remove hair

Bates faculty member Rebecca Herzig is getting media attention for her new book exploring our complicated relationship with hair removal.

Herzig’s book is Plucked: A History of Hair Removal (New York University Press, 2015). She is the college’s Christian A. Johnson Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies.

The Times of London, Times Higher Education, The Economist and The Globe and Mail have published reviews, and she’s been interviewed by New Hampshire Public Radio, Dallas Public Radio and, on Feb. 10, by Southern California Public Radio.

During the SCPR radio interview, a listener posted a comment on the show’s Facebook page, saying that a local middle school science teacher told her students that Asians “are a more evolved race, as evidenced by their reduced amount of body hair.”

Host Larry Mantle asked Herzig to comment on that anecdote, and she noted that skewed ideas about race, evolution and hair may have begun as a reaction to Charles Darwin. She said:

Darwin changed the way people thought about the human relationship to animals. When they saw that there was a continuum, rather than a bright line separating humans and animals, it became more culturally important to maintain that boundary, and hair was a perfect way to do it: You can literally shave off your animalness to help maintain that boundary.

And if hair removal became a way to affirm our human identity, it’s not hard to imagine how hairlessness might become linked, in some minds, with ideas about human evolution or racial superiority.

Elise Kornack ’09

Take Root grabs hold of New York City diners

An art and visual culture major before she became a chef, Elise Kornack exhibited “Head to Toe,” wire and graphite on paper, during the 2009 Senior Exhibition.

New York City food writers are taking note of Take Root, the Brooklyn restaurant run by Elise Kornack ’09 and her wife, Anna Hieronimus.

The restaurant has received a great New York Times review, and last fall got a “best new restaurant” nod from Esquire.

Kornack herself was featured recently by Food Republic, a profile that traces her career from Bates art major to Brooklyn restaurateur.

A tiny place in Carroll Gardens, Take Root is as intimate as a Bates first-year seminar. It seats just 12 and offers one seating per night, Thursday through Saturday.

Food Republic writer Richard Martin says that his meal at Take Root “was not the precious market-driven set menu place I was expecting.”

He continues: “For all the accolades and chatter, Kornack’s cooking is ultimately personal and thoughtful rather than flashy or stylized. It’s a refreshing approach, and one that puts her at odds with the wizards of the city’s other heralded tasting menus, where foams, trompe l’oeil and technique are part of the show.”