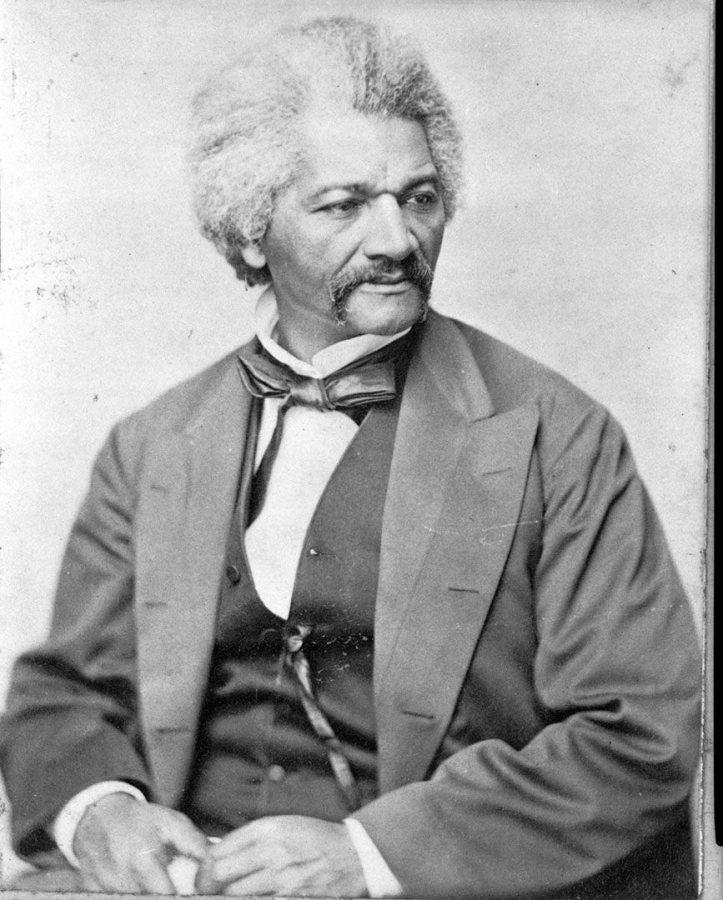

In November 1874, Frederick Douglass, traveling the country giving a series of lectures, stopped at Lewiston City Hall, where he spoke about abolitionist martyr John Brown.

Douglass, the great author, orator, and abolitionist, had come at the invitation of the Bates senior class, but the likely real reason was more personal: his friendship with fellow abolitionist leader and Bates founder Oren Cheney and his family.

Frederick Douglass, photographed by George Schreiber in April 1870. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

In 1840, for example, when Douglass visited New Hampshire to speak at a meeting of the New England Antislavery Society, he stayed with Cheney’s father and mother, Moses and Abigail, at the Cheney home in Peterborough, which was a station on the Underground Railroad.

As an adult, Oren Cheney created his own Underground Railroad stop, helping fugitives reach Canada. He hosted Douglass in his home several times, along with such other anti-slavery advocates as Austen Willey, Henry Wilson, Sojourner Truth, and Frances Watkins.

“By allowing abolitionists and particularly black abolitionists to stay at his home in Maine,” wrote Tim Larson ’05, in a senior honors thesis published during Bates’ 150th anniversary celebration, “Cheney was clearly making a stance about racial boundaries.”

Cheney and Douglass were both giants in their worlds. Cheney was a vocal abolitionist, couching his position in his Free Will Baptist faith. He became a Maine state legislator who made unabashed speeches advocating for both abolition and prohibition.

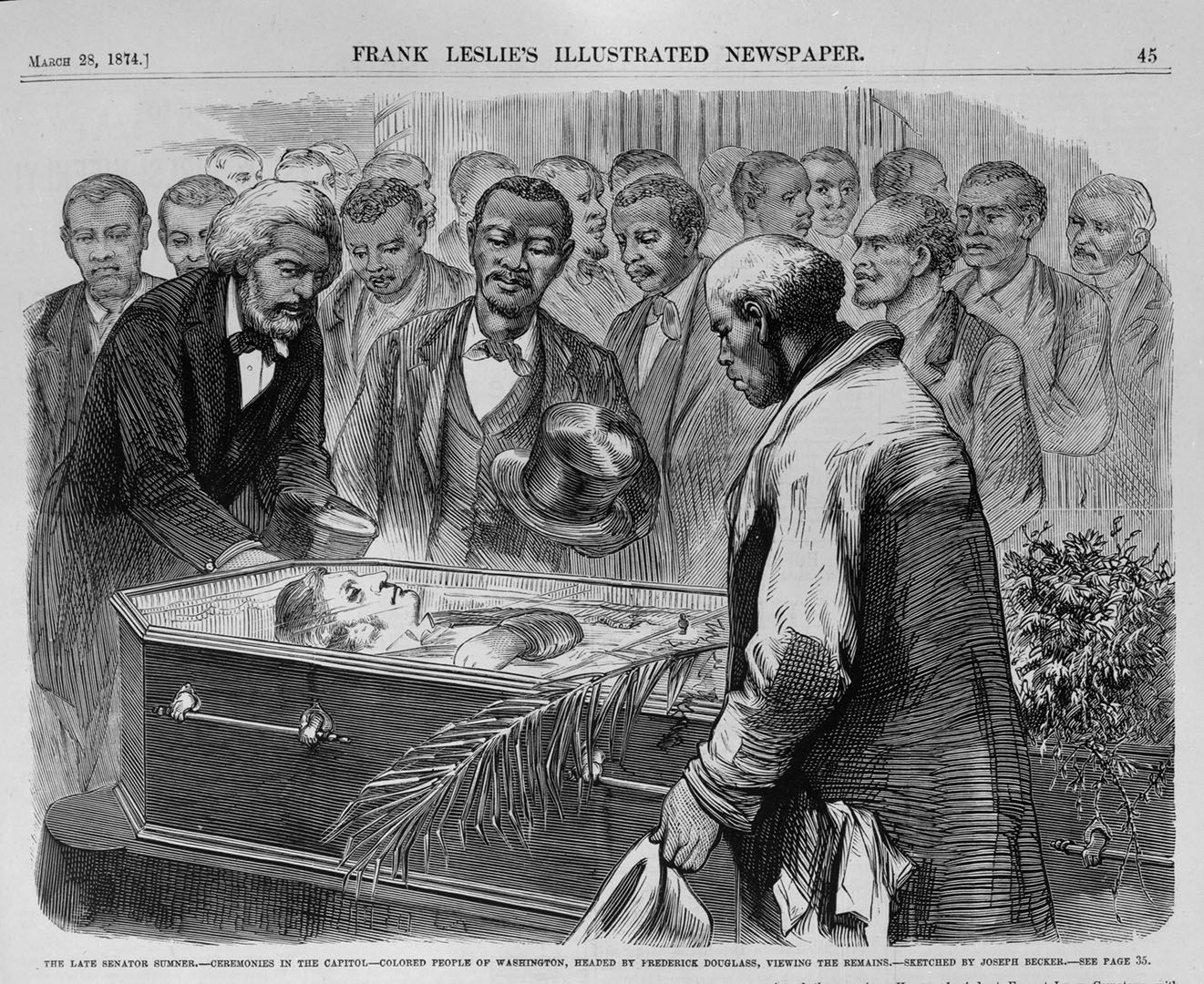

Frederick Douglass (left) pays respects to U.S. Sen. Charles Sumner, whose body lies in state in the U.S. Capitol in March 1874. A prominent abolitionist, Sumner, who was close friends with Bates founder Oren Cheney, gave Bates its enduring motto, “Amore ac Studio” — “with ardor and devotion.” (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

He circulated his anti-slavery position as owner of the Morning Star newspaper, though, he asserted, “we can find no language that has the power to express the hatred we have towards so vile and so wicked an institution.”

Douglass, of course, wrote best-selling autobiographies, published the North Star, and was involved in the Colored Conventions Movement, which before and after the Civil War advocated for social and political equality for African Americans. He traveled widely, giving orations against slavery and racism.

As the group tried to enter, the proprietor “rudely repulsed” Douglass.

Douglass also went into politics and in 1852 was named a delegate to the presidential nominating convention of the Free Soil Party, which opposed the expansion of slavery. On the way to the convention in Pittsburgh, Douglass — and Cheney, the sole delegate from Maine — joined a group of delegates for a dinner stop in Alliance, Ohio.

Dinner was ready for the delegates at a hotel in Alliance, but as the group tried to enter, the proprietor “rudely repulsed,” Douglass wrote in an autobiography.

Bates participated in a “transcribe-a-thon” on Frederick Douglass’ 200th birthday, Feb. 14, helping to create searchable digital versions of African American historical documents. Here, Wesley Chaney and Patrick Otim, assistant professors of history, watch a Facebook Live presentation on Douglass, the Colored Conventions, and the Freedman’s Bureau. Between them is Otim’s cardboard cutout of Douglass. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Cheney’s wife, Emeline, and Douglass, both writing about the incident some decades later, each ended the story differently. Emeline Cheney, writing about her husband’s political activity, said the proprietor “backed right down” when the delegates refused to eat without Douglass.

Douglass, including the incident as one of many in which he was refused food, travel, or lodging because of his race, wrote that the delegates refused to eat. Further, when the group came back through Alliance after the convention, it again refused to go into the hotel, and a dinner for 300 “was left to spoil.”

Such instances of racism did not end after the Civil War, and Douglass continued to speak and write against discrimination and for social and political equality.

Cheney and Douglass’s affinity lasted a lifetime. “Cheney clearly felt that there was a divine unity among all people regardless of race,” writes Larson. When Douglass died in 1895, Cheney attended the funeral. Both men, according to Emeline Cheney, asserted that God “hath made of one blood all nations of men.”

This year, on Feb. 14, Douglass’ 200th birthday, Bates participated in a “transcribe-a-thon,” helping to create searchable digital versions of African American historical documents in order to make historical and genealogical research easier.