Al Fereshetian is excited.

It is a perfect spring day in Lewiston, Maine, and Fereshetian is finally getting to spend some quality time with his discus throwers after a few weeks of rough weather.

“It’s like we’re in Florida!” Fereshetian says to his charges, who include senior captain Adedire Fakorede ’18 of Newark, N.J., soon to be a three-time All-American. “Hey, after this, who wants to go to Dairy Joy and get some ice cream?”

Today is a great day to coach Bobcats, and Fereshetian makes sure his throwers come over to his tablet after each throw to review video of exactly what they are doing right and exactly how they need to improve.

“It sure beats the old days of using an 8 mm camera,” Fereshetian laughs. “We’d get the footage a week later!”

Fakorede is the latest in the great tradition of Bates throwers, and the latest to praise his coach’s knack for bringing out the best in their shot put, weight, hammer, discus, and javelin efforts.

“Coach Fresh is a friend, a dad, a brother, and a mentor,” Fakorede said. “He just does it all.”

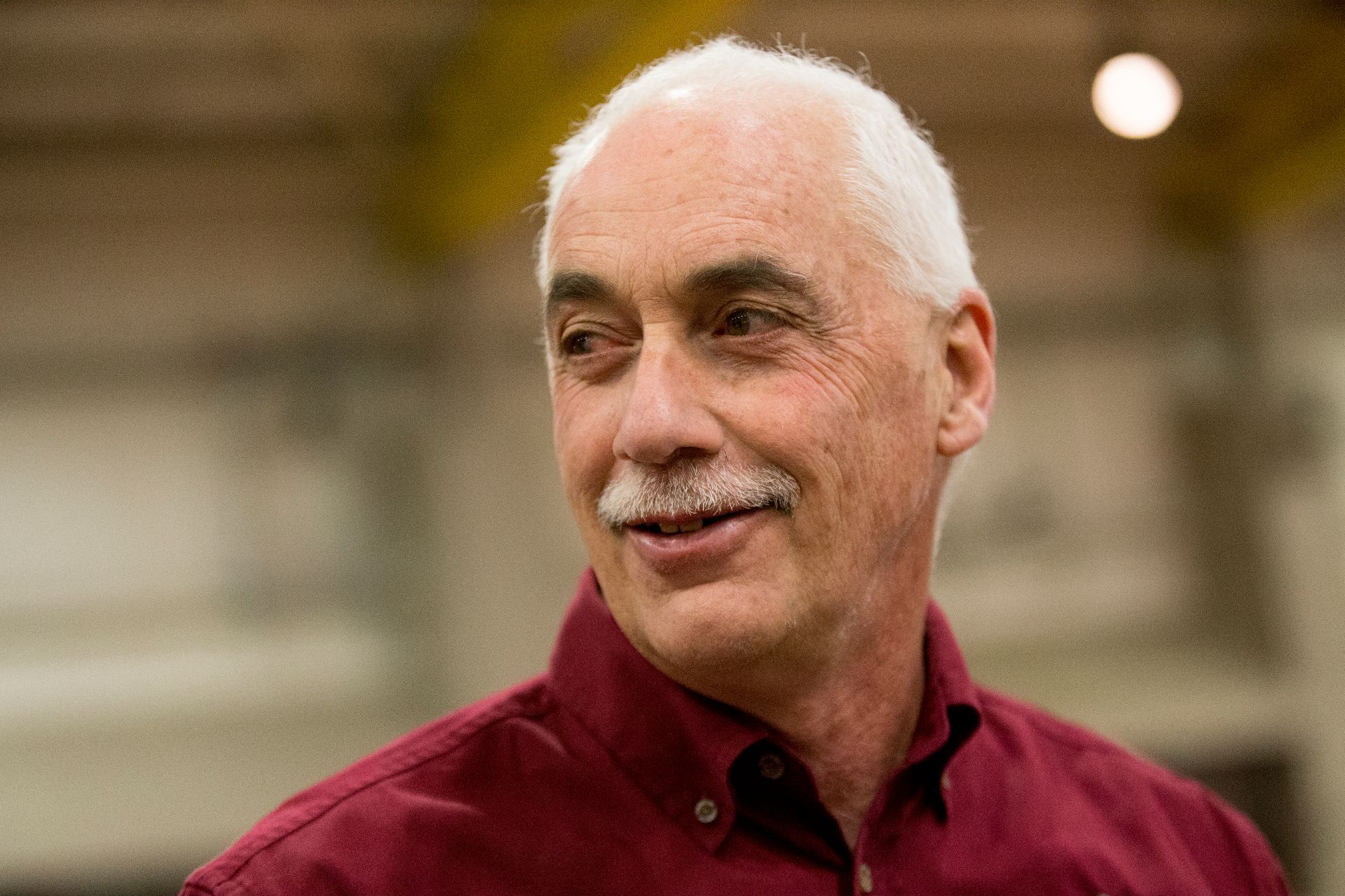

With a remarkable record of coaching throwers to national achievement, Al Fereshetian has headed the Bates men’s cross country and track and field programs since 1995. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Fereshetian has been doing it all for his Bates athletes since 1995, before any of the current Bobcats were born, carrying on — and building upon — the great post-World War II reputation of Walter Slovenski. In 43 years, Slovenski produced 26 All-Americans overall, including five national champions, such as Wayne Pangburn ’66, a national titlist in the hammer throw in 1965 and 1966, whose success was a harbinger of things to come for the Bobcats.

From late in Slovenski’s tenure and continuing through Fereshetian’s — 1991 to present day — Bates has produced at least one All-American in either the weight throw, the shot put, the hammer, the discus, or the javelin every year. That is a streak of 28 years and counting. And all told, 16 of the 21 national champions in Bates track and field history have been throwers.

Bates has 31 varsity sports and among the current head coaches, Fereshetian is the second-longest tenured. His cross country, indoor, and outdoor track teams are regularly among the top handful in New England and, by extension, all of Division III. For example, Bates has placed among the top three teams at the New England Division III Outdoor Championships in each of the past nine years.

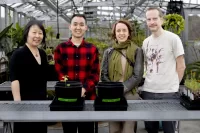

In March 2016, Al Fereshetian works with Nick Margitza ’16 of Waterville, Maine, and Adedire Fakorede ’18 of Newark, N.J., in their final tuneup before departing for the NCAA Division III Indoor Track and Field Championships. (Josh Kuckens/Bates College)

But to understand his success, first you have to understand him.

Fereshetian was born in Arlington, Mass. The son of first-generation Armenian American doughnut makers, Fereshetian spent his formative years in New Hampshire playing a lot of hockey. In eighth grade, as he started running to stay in shape for hockey, Fereshetian discovered a passion that changed the course of his life.

“Hockey required a lot of equipment, but with running, as long as I had a pair of shorts and a pair of shoes, I could go out and make myself better,” Fereshetian said. “And I did.”

Fereshetian went to Bentley College planning to major in business.

“I would study for an accounting exam for maybe two minutes, but I found myself constantly thinking about running,” Fereshetian said. He decided he wanted to coach, and developed a 10-year plan, to culminate in a Division I head-coaching job by the age of 30.

It was a far cry from taking over Charlie’s Donuts, the family business.

“It was a shock to my parents but they came around and were very supportive,” Fereshetian said. “At that point, when I talked to my parents, I had already worked out my career plan. I knew what I had to do.”

Fereshetian transferred to the University of New Hampshire and didn’t wait for graduation to begin coaching. He headed up the track and cross country program at Somersworth High School and volunteered with the UNH women’s track and field team.

For the first time, he focused on the throws, bringing atomic precision to the task.

“I worked nights as a security guard at the Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant when it was under construction,” Fereshetian said. “The beautiful thing about working in a facility like that is they have the most amazing polished concrete floors.”

“My job was to stay awake all night. The best way for me to stay awake was to move! So I did a lot of turns throughout the night. It allowed me to get a great feel for the throws. I had to get that feel so I could convey it to the athletes.”

In October 2016, Al Fereshetian exhorts his cross country runners at the end of the Maine State Championship in New Gloucester. Fereshetian, says a colleague, is the rare coach who effectively trains both runners and throwers at a high level. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Jim Boulanger is in his 33rd year as the head coach at UNH. But when Fereshetian arrived, Boulanger was still an assistant. Boulanger had no background in track at all and Fereshetian, with his running background, was learning to coach the throws. The two became fast friends, bouncing ideas off each other, and growing as coaches together. They are still close.

“Al is a throwback guy like myself,” Boulanger said. “He is not a specialist; he can do anything.”

“I always tell people that if you posted a job description that said ‘cross country and throws coach,’ Al is one of the few people in the country who could do that legitimately at a high level.”

After graduating from UNH in 1983, Fereshetian landed a position at the University of Kansas where he coached, among other athletes, two javelin throwers who qualified for the 1988 United States Olympic Trials.

“I’ll never forget this. My paycheck at Kansas came out to $111.11 per month,” Fereshetian said. “It keeps you humble, but the experience was priceless.”

“The most important people should be the ones you are currently coaching. That has always been my philosophy.”

In 1989, Fereshetian became the head coach of the Division I program at Appalachian State University, where his success eventually earned him a spot in the university’s Athletics Hall of Fame.

He was 30 at the time of his appointment. He had executed his 10-year plan to perfection.

But seven years at Appalachian State convinced Fereshetian he needed a change of scenery. It was time for a new plan.

“Division I is a business, and we were always so focused on the people we were trying to get to replace our current athletes,” Fereshetian said. “Recruiting is critical and it has to happen. But the most important people should be the ones you are currently coaching. That has always been my philosophy.”

Bates College and the Division III ethos were the perfect fit.

Fereshetian succeeded Slovenski, and he knew from experience that the best way to replace a legend is not to.

“I heard all the Walt Slovenski stories. But when I started at Appalachian State I heard all the Bob Pollock stories,” Fereshetian said. “There is always some pressure, but the bottom line is, I can’t be Walt Slovenski. I have to be myself.”

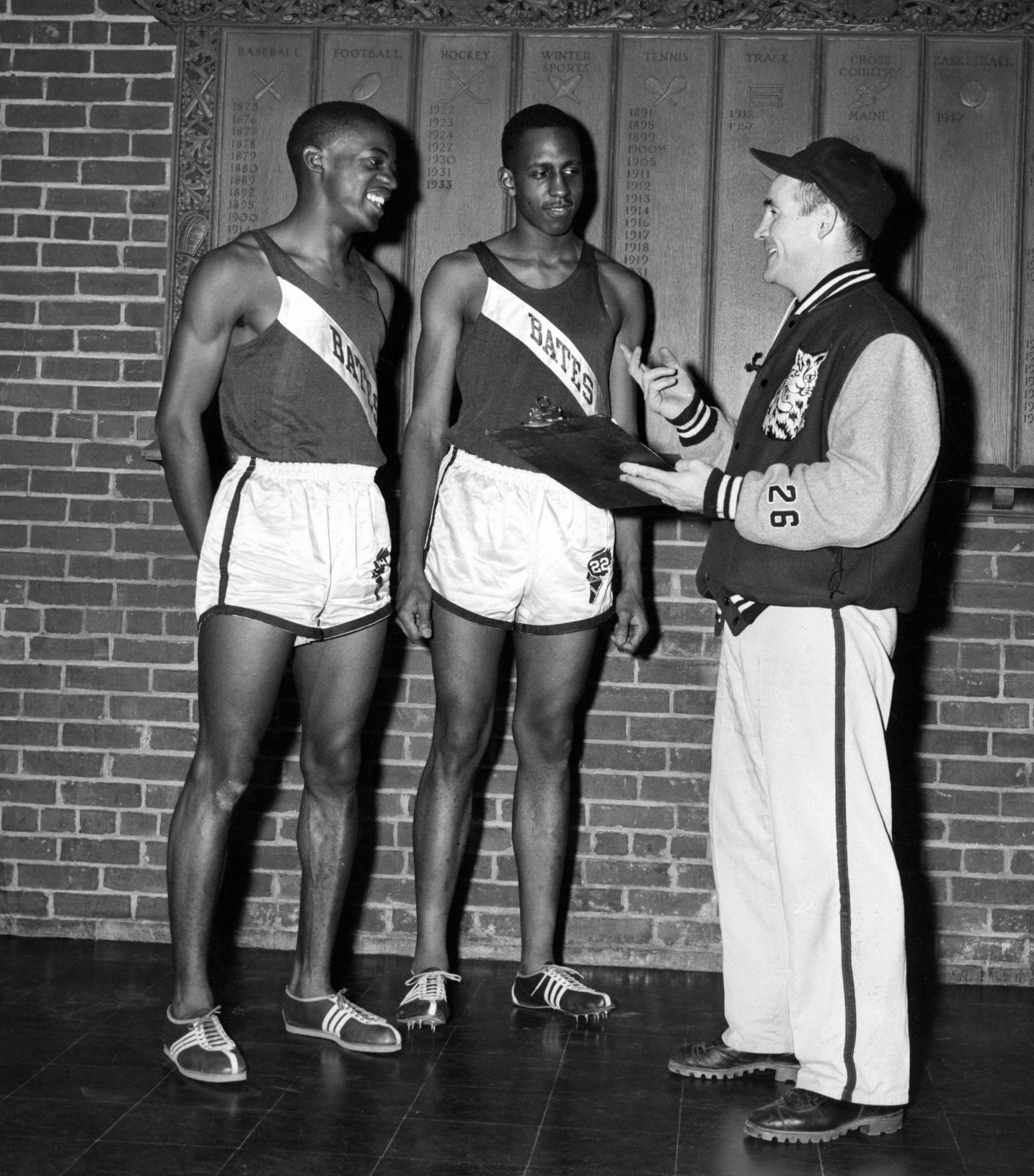

The best way to succeed a legend like Walter Slovenski, seen here with his great trackmen Rudy Smith ’60 (left) and John Douglas ’60, is not to. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

He had the time to be himself thanks to one of Bates’ great assistant coaches, Joe Woodhead. A Maine high school coaching legend, he had retired in the mid-1980s and then joined the Bates staff under Slovenski. With Woodhead coaching the throwers, Fereshetian was freed up to focus on building his program.

“I knew the throwers were in great hands with Joe,” Fereshetian said. “The truth about track and field is, I love every aspect of it. When I was at Appalachian we had national-caliber triple jumpers, and I loved that.”

“When Al arrived my junior year, the program as a whole shifted.”

Woodhead was a hammer and weight throw expert. When a Bates javelin thrower began to open some eyes — eventual three-time All-American Heather Bumps ’97 — it was time for Fereshetian to take on his first pupil.

“When Al arrived my junior year, the program as a whole shifted,” Bumps said. “My first two years, there was definitely a men’s team and a women’s team. Although we shared the same space, we practiced and competed separately. But when Al got there, he and women’s head coach Carolyn Court worked together to build a feeling that this was one track and field team.”

With his ever-present tablet in hand, Al Fereshetian coaches the hammer throw at the Maine State Men’s Outdoor Track and Field Championships at Bates on April 20, 2018. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Bumps had earned All-America honors as a sophomore the year before Fereshetian arrived. Then in the spring of 1996 under Fereshetian’s tutelage, she set a Bates record that still stands today, unleashing a throw of 144 feet, 7 inches.

“His really deep technical knowledge was a big change,” Bumps said. “I had kind of been skating by on natural talent up until I started working with Al. I can’t even imagine how many hours I watched video of my throwing. It was a completely different approach than what I had experienced to that point.”

In 1998, Billy McEvila ’99 won the national title in the 35-pound weight throw, the Bobcats’ first NCAA championship in the throws since Steve Ryan ’83 took home the title in the javelin 15 years earlier.

In the 2000s, Bates throwers upped their game to a new level, with Liz Wanless ’04 winning national titles in the indoor and outdoor shot put in 2004. Wanless became the first Bates women’s track and field athlete to win a national title in any event.

In February 2009, 16-time All-American Keelin Godsey ’06 hugs longtime throwing coach Joe Woodhead during an event dedicating the throwing circle in Merrill Gym in Woodhead’s honor. Godsey won two national championships in the women’s hammer. (Louisa Demmitt ’09/Bates College)

Meanwhile, Keelin Godsey ’06 was becoming the most decorated Bates track and field athlete ever. Earning an astounding 16 All-America honors in the throws from 2004—06, Godsey took home two national titles and set an NCAA Division III record in the hammer along the way. He later became the first openly transgender athlete to compete for a spot on the U.S. Olympic team.

Woodhead had his throwers clicking on all cylinders, with Jamie Sawler ’02 (weight and hammer) and Noah Gauthier ’08 (weight) winning national titles during this period as well.

And in February 2009, following extensive renovations to Merrill Gymnasium and Slovenski Track, the throwing area was renamed the “Joseph Woodhead All-American Throwing Area” in a surprise ceremony for the beloved coach.

By then, Fereshetian had been on the periphery of the throwers for more than a decade. “Coach Fresh recognized Coach Woodhead’s success in the throws,” says two-time All-American Chris Murtagh ’11. “There was no need for a change.”

And then, for sad reasons, there was a need for a change when, in February 2010, Woodhead fractured his femur in a collision with a Middlebury runner on the track at MIT.

As he recuperated, Fereshetian stepped in to train the throwers. Three-time All-American Rich McNeil ’10 and six-time All-American Vantiel Elizabeth Duncan ’10 finished their careers on a high note with All-America honors that spring.

But in October 2010, Woodhead died at age 76. “We were heartbroken. He was like a grandfather to me,” Murtagh said.

The throwers dedicated the 2011 season to Woodhead, and Fereshetian introduced a “full-scale, disciplined approach” to being a thrower, Murtagh says, one that “included recording everything on video, nutrition, flexibility, and yoga. He went all in. ”

“We went from being big guys who threw the weight to becoming better all-around athletes.”

“Coach Fresh is a thrower trapped in a runner’s body,” McNeil said, referring to his coach’s outsized, big-man appetite (doughnuts, of course, and ice cream) as well as his focus on technique, which is at the core of a thrower’s world. “Al is a technician. He is always willing to adjust certain things to help his athlete out. He evens names drills after student-athletes.”

Al Fereshetian works with Zack Campbell ’19 of Brooklyn, N.Y., during the Maine State Men’s Outdoor Track and Field Championships at Bates on April 21, 2018. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“There’s technique to everything,” Fereshetian says. “There’s technique to driving, there’s technique to opening a door. And there’s technique to throwing.”

Just the way Fereshetian created his own plans as a young coach, he creates plans for his athletes, and lets them do the execution. He lays the foundation, says Fakorede, then “builds it up, brick by brick.”

Fereshetian’s coaching talents helped David Pless ’13 go from throwing the shot put 46 feet as a first-year to 56 feet and the indoor national title in 2011 as a sophomore.

“Coach Fereshetian is someone who believed in me at all times even when I didn’t believe in myself.”

For the first time in his Bates career, Fereshetian got to present the All-America awards in the shot put because his athlete came in first. So Pless got his award from Fereshetian as did fellow All-American Ethan Waldman ’11. Murtagh, too, received All-America honors at the 2011 NCAA Indoor Championships, in the weight throw.

Waldman’s father, Ira ’73, was at the meet. He will never forget looking at Fereshetian as he handed out the awards.

“He puts everything he has into making these athletes perform to the best of their ability,” Waldman said. “You could see the pride on his face. You could see the tears welling up in his eyes.”

“Coach Fereshetian is someone who believed in me at all times even when I didn’t believe in myself.” Pless said. “Through all the All-American awards and national championships, the constant was Fresh.”

In never gets old: In March 2013, and for the third year in a row, Al Fereshetian presents the championship shot-put trophy to David Pless ’13 at the NCAA Division III Indoor Track and Field Championships. (Video courtesy of Ira Waldman ’73)

Fereshetian cares deeply. He once drove Murtagh and Pless from Washington, D.C., to Lewiston, Maine, after their flight back from nationals got diverted. Normally the 600-mile trip takes 10 hours, but Murtagh was graduating the next morning. So they did it in eight.

Fereshetian has been the steward of the Bates throwing legacy, but his throwers have also taken it upon themselves to keep it thriving. The passion for the program Bates throwers show every day mirrors their coach’s.

During his time as a Bates thrower, Fakorede was often reminded of his responsibility to carry on the tradition.

Those reminders came as texts, as Fakorede is part of a group chat that includes McNeil, Waldman, Murtagh, Pless, David Hardison ’13, Eric Wainman ’15, Sean Enos ’15 and Nick Margitza ’16. That is a combined 32 All-America awards, in case you are counting.

Their strong back-and-forth with Fakorede kept him focused and motivated to do his best every meet. He heard from them whether he set a personal record or if he underperformed.

Enos, who earned nine All-American awards, was a senior when Fakorede was a first-year at Bates.

“I was lucky enough to know Chris and Rich in high school, so they told me about the legacy before I even came to Bates,” Enos said. “Pless took me under his wing when I got here, teaching me how to prepare myself, and I did the same thing for Adedire.”

Al Fereshetian gathers his athletes during the 50th Maine State Indoor Championships on Feb. 3, 2018, in Merrill Gymnasium. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Fakorede paid it forward by mentoring first-year John Rex of Andover, Mass. Rex, in turn, broke Fakorede’s freshman record in the hammer.

“I hope he’s the future and face of this program,” Fakorede said. “I’ve been telling him that talent is not the be-all-end-all when it comes to the throws. You have to put in the work inside and outside the circle.”

On that perfect spring day, Fereshetian takes Fakorede and Rex to Dairy Joy following their workout, as promised. They start talking about baseball and Fereshetian brings up one of his favorite pitchers from years ago: Dan Quisenberry.

Neither Fakorede nor Rex has heard of the former Kansas City Royals closer, known for his “submarine” style of pitching.

“Oh,” says Fereshetian taking out his tablet, “you’ve got to see this.”

They look intently, and Fereshetian smiles.

“Watch him throw.”