Scenario:

You’re agents of MI6, the British foreign intelligence service. You recently caught a Russian spy who tells you there’s a “mole” among your ranks, leaking secret information to another government.

Your task, Elly Rostoum ’07 told the students in her Short Term course on intelligence and national security, is to root out the mole.

“Spies, Special Agents, and the Presidency,” one of five practitioner-taught courses offered this term through the Center for Purposeful Work, is designed to “mimic a day in an intelligence officer’s life,” Rostoum said.

In her Short Term course on intelligence and national security, Elly Rostoum ’07 walks students through a “find the mole” simulation, in which they have to find out which fictional MI6 agent is leaking information to a foreign government. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

Rostoum, currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Massachusetts Boston, majored in politics at Bates and worked in management consulting in the oil and gas sector before serving on the National Security Council at the White House.

The Short Term course includes learning about world geography, transforming disparate data into insights you can act on, and a series of simulations ranging from a doomsday planning scenario to today’s mole hunt.

It’s all very hands-on, said Arianna Fano ’19 of Lincolnshire, Ill., a politics major. “We get to do lots of different things we wouldn’t normally get to do during the school year,” she said.

Fano was perhaps the best able to think like a mole, having been one herself. At the beginning of the term, she found a note in her bag telling her to figure out the hometown of one of her classmates; as a sort of pre-simulation mole hunt, her classmates had to guess who was the spy among them.

(Because Fano could simply look up her classmate’s hometown on a student directory and act natural otherwise, she stayed well-hidden.)

The instructional note was anonymous, so Fano had to verify that it was indeed from Rostoum. “I had to match the handwriting on the note to the handwriting she was writing on the board,” she said. “So I got to embody at least a little bit of what a spy does just in this small exercise.”

Now, she and her classmates had a much bigger exercise ahead of them. Rostoum handed out pictures and biographical profiles of (entirely fictional) MI6 agents and their spouses, the suspects’ phone records and purchase receipts, and financial irregularities that the agency flagged.

In addition to identifying the mole, the students had to discern how the mole gathered information and use the documents to construct a narrative. Rostoum divided the students into three groups — such separations are common in intelligence work in order to avoid mutually reinforcing similar ideas, she said.

Settled in different rooms in Hathorn Hall, the students got to work.

One group quickly zeroed in on “Zubida,” a British-born schoolteacher pictured wearing a niqab. She was married to “John,” the head of the MI6 Syria desk. Every few weeks, she’d get a call from an unknown number; the next day, she would go to a particular London hotel.

Elly Rostoum ‘07 helps a group of students think through their mole hunt. What patterns could they see in phone records? In purchase receipts? (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

The husband, John, had recently been flagged for opening lines of credit without reporting them to MI6. The purchases? Thousands of dollars of lingerie, jewelry, vintage cars, and expensive boarding schools. Had Zubida opened credit cards in John’s name without telling him?

A student scanned the taxi receipts of “Archie,” John’s boss at MI6. He, it appeared, was going to the same hotel as Zubida on the same days. An affair?

Archie’s movements were unusual in other ways. One day he took a cab ride to a district of government buildings that, based on the distance traveled, shouldn’t have cost the $50 he paid for it. Then, according to GIS data, he went to another hotel that Zubida also frequented and bought two Scotches there.

Suspicious, all. But why, the group wondered, would Zubida pass along state secrets? How would she even know them? Was she a conservative Muslim, since she wore a niqab?

And what about information they hadn’t yet considered: several hours-long phone calls to Zubida from Syria, other calls from European and Middle Eastern countries, a police report that suggested spousal abuse?

As theories swirled, Rostoum circulated among the groups, dropping hints. Think about why Zubida’s “unknown” phone calls lasted less than a minute, she told the first group. And focus on the receipts: taxi rides, expensive Scotch.

Though the Bates students’ mole hunt was a pared-down version of similar simulations in graduate-level courses, they still had to sift through a mountain of phone records, pictures, bios, receipts, and satellite images. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

The records the students were given might seem overwhelming, Rostoum said, but it was a pared-down version of what you might find in a graduate-school simulation: months of phone records, reams of receipts, sifted through over the course of a semester.

The class period wound down; the group had a possible narrative but not a good idea of who the mole was. They got their information together just as their classmates reentered.

“Was it hard?” Rostoum asked the class. They nodded. “Was it confusing? Do you have a greater appreciation for the work intelligence officers do?” They did.

“Don’t fall too much into the stereotypes.”

The first group’s best guess: John was the mole, using Zubida to pump information from his boss, Archie, through an affair, and passing on the information to — Syria? Russia?

The second group inferred that Archie was the mole. John was clearly abusing Zubida, so out of revenge she passed information to Archie from John; Archie and Zubida were possibly planning to frame John.

The third group said Zubida and Archie were having an affair, but not of the heart. Zubida, the niqab-wearing schoolteacher wife of a secret agent, was moonlighting as a high-end escort without her husband’s knowledge. Archie was one of her clients.

Each mole-hunting group zeroed in on Zubida, the wife of an MI6 agent. Why was this schoolteacher meeting her husband’s boss in a hotel every month? (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

But the mole? They didn’t know.

Rostoum said the third group was close. Zubida was in fact an escort. Her work necessitated the purchase of expensive lingerie, which she financed by opening lines of credit in her husband’s name — and John, oblivious, didn’t report the new credit cards and got in trouble with MI6 for it. Zubida’s clientele was international, hence the many calls from other countries.

Sordid, to be sure. But completely irrelevant.

Rostoum brought the class back to the beginning of the exercise: A Russian agent told them they had a mole. Where in Zubida’s story was Russia?

Archie was the mole, Rostoum said. Every few weeks, he’d meet his Russian handler at one hotel or another, at least once over glasses of Scotch.

The handler, not Archie, was the one who used Zubida’s services — usually right before the handler met Archie for the leaked information. That explained why Zubida and Archie would end up at the same place on the same day; Zubida had nothing to do with the espionage.

Case closed.

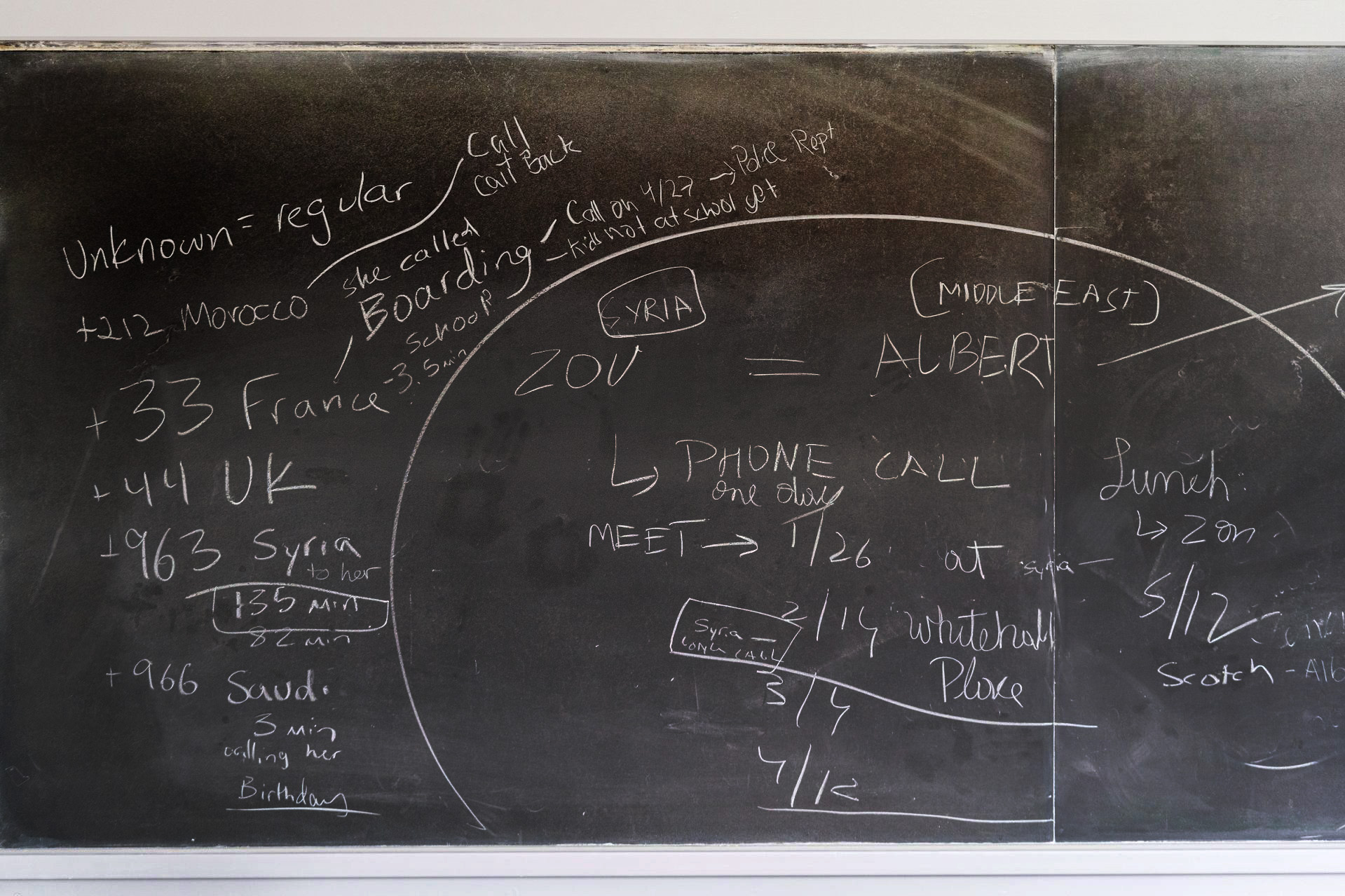

One mole-hunting group made use of the blackboard, plotting out dates, times, and locations. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

Rostoum urged her students to question their own assumptions, and to remember that, since intelligence is a human discipline, it’s important not to dehumanize the characters in the mole hunt.

“Too often there’s a Hollywood-ization of intelligence,” Rostoum said. “One thing to keep in mind is that even the target and the spies are both human. There is a human component that includes topics that are in our everyday life.

“The other thing is not to fall too much into the stereotypes, of a woman who’s covered, which might or might not suggest religiosity or modesty.”