In 1876, just as the post-Civil War Reconstruction stalled and white politicians began to roll back the rights of formerly enslaved people, the Emancipation Memorial was erected in Washington, D.C.

![The Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C., embodies the complex definition of "emancipation" in U.S. society, says Charles Nero, the Benjamin Mays Professor (Photo by yeowatzup [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)])](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2019/06/Emancipation_Memorial_Washington_DC_172659694-702x900.jpg)

The concept of emancipation is more complex than the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C., might suggest, says Bates professor Charles Nero. (Photo by yeowatzup / CC BY 2.0 / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)

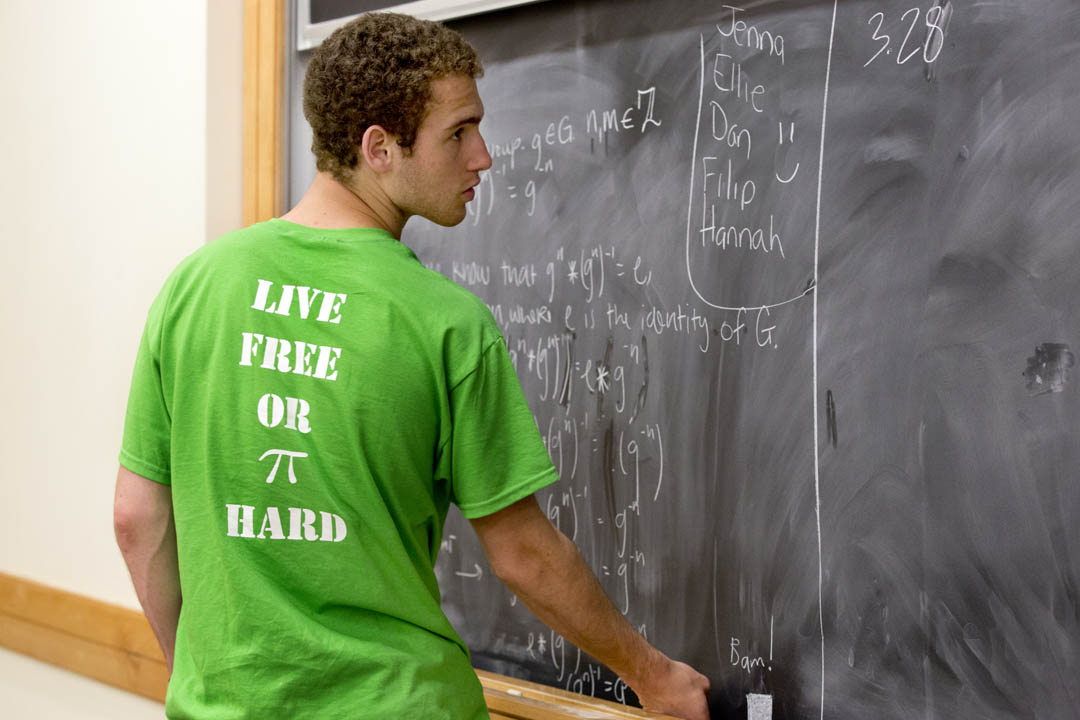

The history and ideology behind the word “emancipation” are complex, Bates professor Charles Nero told an alumni audience at Reunion on June 7.

Did emancipation happen as depicted in the statue — as a white statesman benevolently freeing the slaves — or was it the result of a war of liberation in which black Americans won their freedom through their own struggle?

The Benjamin E. Mays ’20 Distinguished Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies, Nero approached his talk — on the life of his professorship’s namesake, civil rights icon Benjamin Mays — with the rhetorician’s attention to the power of words and images.

The 50th Reunion Seminar, organized by the Class of 1969, centered on Mays’ most famous quote relating to Bates, from his autobiography, Born To Rebel.

Mays wrote, “Bates College did not ‘emancipate’ me; it did far greater service of making it possible for me to emancipate myself and to accept with dignity my own worth as a free man.”

Mays’ description of his Bates education is “stylistically very elegant,” Nero said.

When Mays published Born to Rebel in 1971, he’d had many decades to think about emancipation. After graduating from Bates and earning a doctorate from the University of Chicago Divinity School, he served for 30 years as president of Morehouse College.

At Morehouse, Mays mentored future civil rights leaders, including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., becoming known as “the schoolmaster of the Civil Rights Movement.”

Mays’ description of his Bates education is “stylistically very elegant,” Nero said.

Bates professor Charles Nero discusses the concept of emancipation and the life of Benjamin Mays during a 50th Reunion seminar on June 7. Nero is the Benjamin E. Mays ’20 Distinguished Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“He is rejecting this idea of emancipation, the idea of emancipation that is in this statue which surely he knew,” he added. “In other words, he is declaring his own agency, his own command of his future. Bates College played a role in that.”

At the same time, “Bates College is not Lincoln. That’s very important for an African American man to make a statement to that effect.”

Contained in Mays’ idea of emancipation, Nero said, were three additional heavy concepts: religion, gender, and citizenship — all of which Mays used to reject white supremacy.

Mays was a devout Christian minister, and his theology was similar to that of Latin American liberation theology, Nero said. In a 1966 edition of the Bates Alumnus, now Bates Magazine, Mays recalled how, even as a child, he had decided that if God had made black people inferior to whites, he would not pray to that god.

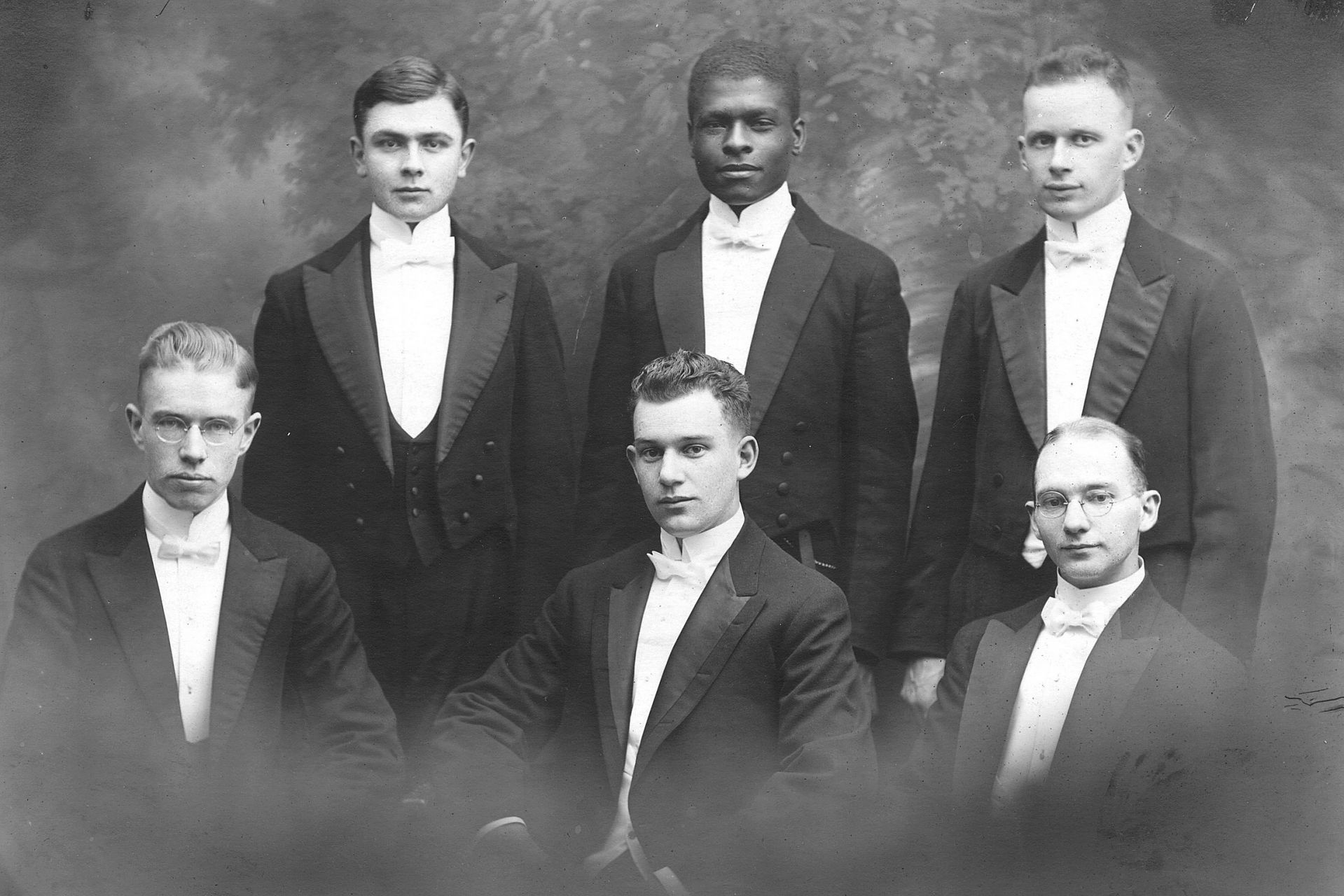

Benjamin Mays (right), with Martin Luther King Jr., was known as “the schoolmaster of the movement” for teaching and inspiring a generation of civil rights leaders, including King, who called Mays “my spiritual mentor and my intellectual father.”

“He is going to reject white supremacy, and if it requires him to reject his faith, he will do that,” Nero said.

Resisting white supremacy also meant asserting his manhood, Nero said. Here, Nero turned to the writings of W.E.B. Du Bois and the sociologist’s famous definition of double-consciousness — the conflicting identities of black men as Americans and African Americans.

Du Bois wrote of feeling best when he could beat his white friends at school or sports. So did Mays — “I thought I would go north for college to compete with whites,” he wrote in the Bulletin. “If I do well there, that would be convincing proof that Negroes are not inferior to white men.”

At Bates, Mays had the opportunity to read the Bible critically, in a way that supported his claim of equality with white men.

“I learned that God was no respecter of persons and that I was right in not believing what I had heard in my childhood — that Negroes were inferior,” he wrote in the Alumnus. He also excelled academically and graduated with honors.

A talented debater, Mays won an oratory award for reciting “Imaginary Speech of John Adams,” by Daniel Webster, a speech that emphasizes the divinity of the American push for independence. That Mays won an award for the speech was profound to Nero.

Benjamin E. Mays (middle, back row) poses with a 1919 debate team. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

“Bates allowed him the testing ground to demonstrate his masculinity, his manhood, his right to not be an outcast or a stranger in his own house — that is, to be a citizen of the United States,” he said.

Nero then asked his audience to consider emancipation as it related to their time at Bates. How did the Class of 1969 grapple with racism and white supremacy?

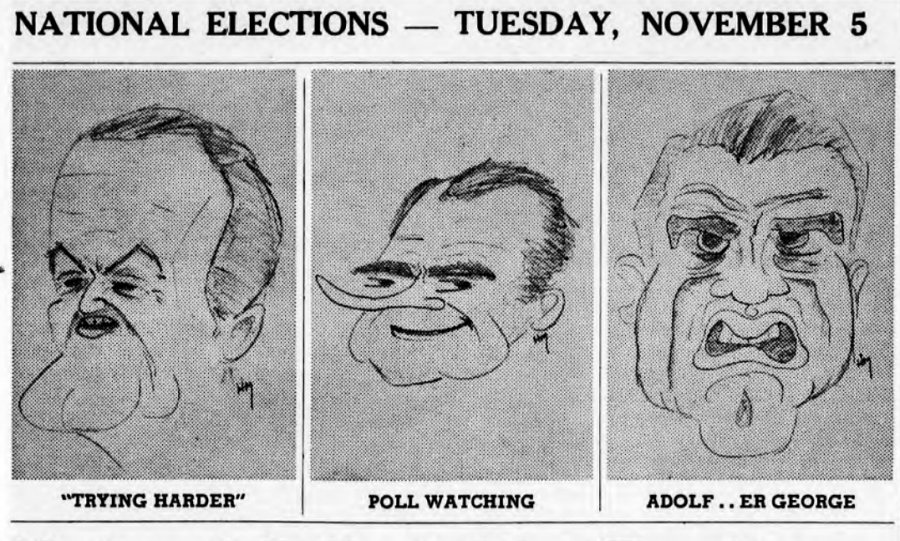

The late 1960s was, of course, a time when social structures of all kinds came under scrutiny. The Vietnam War was starting to attract widespread protest, and the Civil Rights movement was accompanied by the brutal assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., and, earlier, the murders of Medgar Evers and four young girls in an Alabama church.

Depicting candidates Hubert Humphrey, Richard Nixon, and George Wallace, this uncredited political cartoon appeared in The Bates Student the week before the 1968 presidential election.

Student publications that Nero projected showed deep engagement with the 1968 elections. The campaign of George Wallace, though unlikely to find a friendly audience in the liberal Northeast, advertised in The Bates Student. Comedian and activist Dick Gregory, then running as a write-in candidate, appeared on campus.

Students and faculty also wondered how to contend with racism on campus, and how to make Bates more inclusive. Robert Chute, a popular professor of biology, wrote a thundering letter demanding radical changes in admissions, financial aid, and the curriculum.

Dick Gregory’s talk at Bates in February 1968 was described as a “tour de force on civil rights today” by The Bates Student.

One 1968 workshop, “Bates College and the Disadvantaged Black Student,” raised questions about how African Americans were represented.

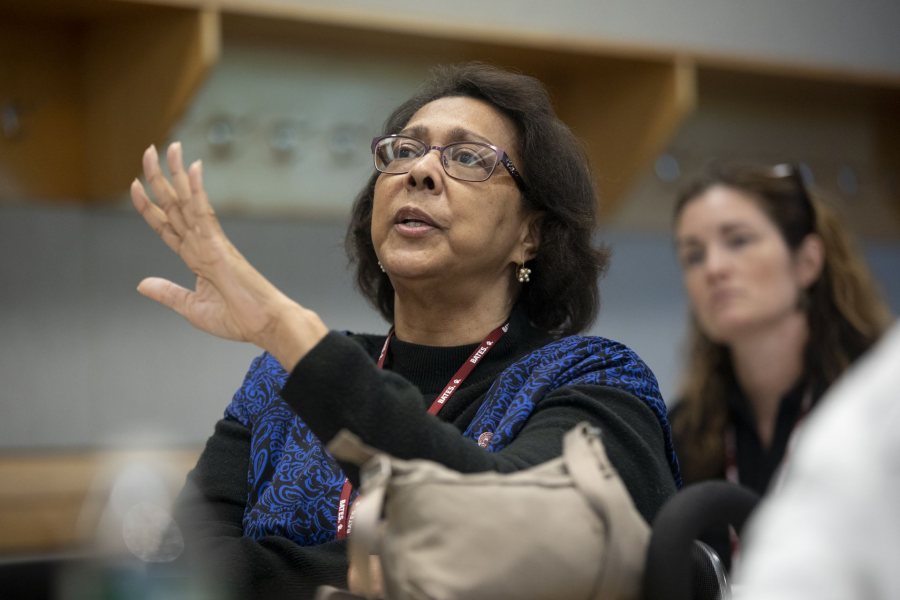

Chantal Berry Dalton ’69, a retired diplomat who was in the Reunion audience, was listed in the workshop’s program as a poetry reader. She said that, as the only black woman in her class, she went to many such workshops and conversations — and did not appreciate how black students were automatically assumed to be disadvantaged.

She said the institutional will to change was there, but it took a lot of work from her and other students of color.

“I spent a lot of hours in a lot of meetings talking about how we were going to change things at Bates,” she said. “It was interesting. It was tiring.”

Chantal Berry Dalton ’69 recalls participating in many of Bates’ efforts to make the college more inclusive. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Other, white, members of the Class of 1969 said they had little recollection of conversations about racism during their time in college. For some, the burgeoning women’s movement was more salient — at the time, women at Bates lived under more restrictive social rules than men.

In fact, for a few, it was only years later that some white audience members understood how white privilege affected their lives.

“Was it your privilege as white people that made you unaware of the kind of labor that emancipation requires?” Nero asked them.

Many of those who spoke up during the talk agreed that emancipation, for Bates, is ongoing.

Alicia Hunter Warner ’94 reminds the audience that questions of race and racism are not historical concepts. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“Like many institutions and individuals, Bates is growing into its own aspirations in a lot of ways,” said Alicia Hunter Warner ’94, a member of the Alumni Council of the Bates Alumni Association.

“I think that there is hope for how we’re changing and what we’re doing as a community, but I do think that we cannot ignore what institutionalized racism in this country is. It is not just our institutions; it’s the fabric of the way we live and interact with each other that keeps self-perpetuating.”