You could say that in her written greeting to visitors entering a museum exhibition in downtown Lewiston, Bates theater professor Christine McDowell bares her sole.

In an introductory text on a gallery wall, McDowell describes a lifelong interest in shoes that stems from her fascination with the creativity and cultural clues represented in footwear. Her shoe jones, she says, earned her the nickname “Imelda Marcos,” after the Philippine political figure “infamous for having over 3,000 pairs of shoes.”

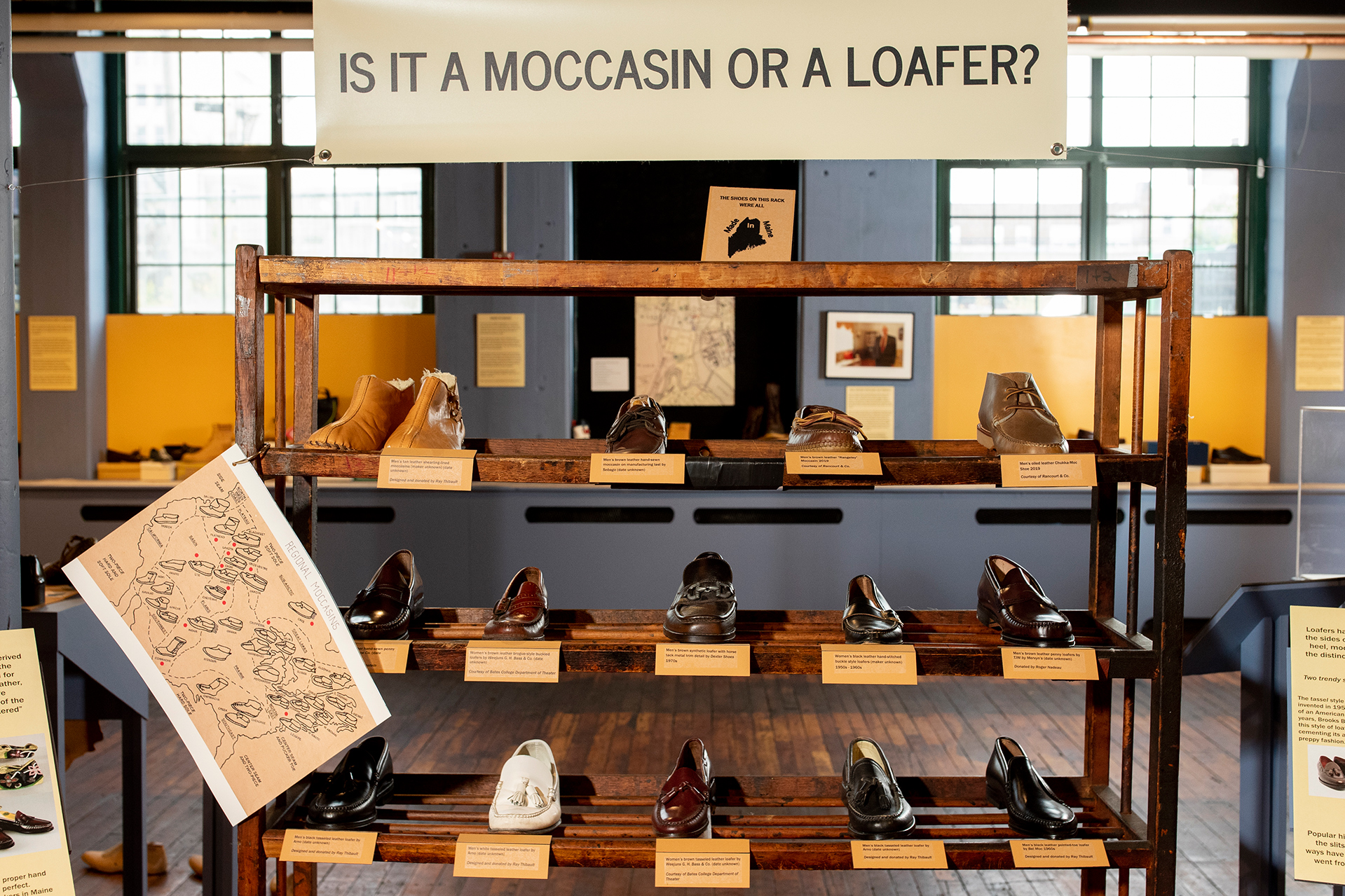

In collaboration with Emma Sieh, collections and exhibits coordinator at Lewiston’s Museum L-A, McDowell put together the museum’s current gallery exhibition, Footwear: From Function to Fashion. McDowell researched the show, designed it with Sieh and others, and provided shoes to display. (The Bates Museum of Art and theater department also loaned shoes, as did the Androscoggin Historical Society, in addition to supplying research materials.)

In fact, from platforms to peek-toes and from slingbacks to Spectators, about three-quarters of the shoes on display come from McDowell’s personal collection of 200-plus pairs. Many of them are concentrated in a spectacular “Wall of Shoes” across an entire wall of the gallery.

Associate Professor of Theater Christine McDowell, left, worked with Emma Sieh, Museum L-A collections and exhibits coordinator, to create the museum’s shoe exhibition. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The exhibition explores the shoe as a medium for social history, the stunning range of footwear styles, and the craft and artistry of shoemaking. And of course, fittingly for a museum dedicated to the history of local industry, Footwear spotlights the economic might that shoemaking once wielded hereabouts.

At one point, Auburn, Maine, was the fifth-largest shoe manufacturing center in the U.S. In the peak year of 1922, some 8,000 workers in 12 major factories turned out 70,000 pairs of shoes per day in Lewiston’s sibling city across the Androscoggin River. (Footwear has coincided with Auburn’s celebration of its 150th anniversary this year.)

An associate professor of theater at Bates, McDowell designs sets and costumes for college productions and teaches various aspects of theatrical design, including fashion. The social and historical meanings of apparel are central to her interest, but she doesn’t overlook another dimension of shoe power.

As a woman standing five feet tall, McDowell states in that prominent wall text, “I readily acknowledge the positive psychological effect shoes can have on those who wear them, and have often felt more confident in a pair of heels.”

Business and brand names associated with the local shoe industry are handwritten on a long strip of paper, displayed with some of the shoes named. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

During a casual tour of the exhibition, which runs through early January, we talked with McDowell about protecting soldiers’ feet from burning desert sand, the last shoemaker standing in Lewiston-Auburn, and, of course, the Wall of Shoes.

You have a lot of shoes.

I never thought of myself as being especially focused on shoes. I collected them as just a natural outgrowth of being a costume designer and being someone interested in clothing as an aspect of social history. I’m fascinated by everyday objects, and how we venerate them and love them. And I can find beauty in any of these particular objects.

Where do you look for shoes?

As the designer for the theater department, a big part of my job is shopping. Every different play presents a different set of challenges, and so you’re always looking in different places. A bunch of the shoes that are on the Wall of Shoes just came from me trolling the racks at Goodwill and Salvation Army, and knowing what to look for.

Footwear has a great century-long timeline of Auburn’s shoe industry, plus other glimpses at local shoemaking, but it’s not purely a historical exhibit. How would you characterize it?

We tried to create an exhibit that would have a broad appeal, that wouldn’t be so narrow that we couldn’t really fill the space, and that would celebrate an everyday pedestrian object, no pun intended, that people don’t normally think about in a museum context. We wanted it to be fun, just celebrating objects — not necessarily steering away from the history, but looking more at something broader and looser.

Shoes are something everybody is familiar with, but have little aspects that you might not think about. Where does a shoe style come from? For instance, modern wedge shoes were invented in the 1930s by this famous shoe designer, Salvatore Ferragamo, which I never knew until I started doing research. You just assume that styles develop gradually over time. But we can point to Ferragamo and say, “This man invented this particular style.”

The museum has a lot of old lasts, the foot-shaped forms that shoes are built around, and you use them as a design element in the exhibit. What do lasts tell us?

One reason that Maine was so successful in shoe manufacturing was the timber industry, because they could make all of the lasts. That’s an example of the kinds of ancillary businesses that helped make the city successful.

There was a huge turnover in shoe companies here. It was an incredibly difficult business to make viable. But because Auburn had such great infrastructure for shoe manufacturing — it had trained employees, manufacturing spaces, machinery — when a company would go bust, somebody else would immediately come in and buy up all the equipment, rehire the workers.

Holding a Western boot, Christine McDowell poses in front of the Wall of Shoes. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

So many shoes of so many different types were made in Auburn, right into the 1960s, yet locally mass-produced shoes from decades past are pretty scarce.

It was very coincidental that I volunteered to be on the museum exhibition committee two years ago. I think about 75 percent of the shoes that you see here are from my personal collection. So in some ways that shaped the exhibit, because it was available material.

Auburn was once known as the White Shoe City, because there was an early manufacturer here, Ara Cushman & Co., of what we would think of as athletic footwear. It involved a new manufacturing process, so it was a leap of faith, but it was very successful here. But I could not find a single surviving example anywhere of this particular type of canvas shoe.

The big Cushman-Hollis factory was demolished in 1972, and that symbolizes the end of the Auburn shoe industry. But there are still shoe manufacturers in L-A and Maine.

One of them is Rancourt & Co. Shoecrafters. They make high-end shoes in Lewiston, and that’s a really tangible link we have to the history of local shoe manufacturing. Those incredibly handsome men’s shoes that you see in the exhibit are from Rancourt.

Rancourt was incredibly generous. They loaned us materials, loaned us shoes, a video about shoe production that we’re showing. They let us tour their factory, which was such a thrill to me, because I got to see shoes being manufactured.

The Plexiglas display shows the 29 pieces of an “exploded” Rancourt shoe. Intact Rancourts are mounted on the wall at left. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

What are some of your favorite shoes in the exhibition?

There’s a pair of traditional Russian folk shoes made out of a material called bast, which is from tree bark. They were actually hand-woven for me, so it was nice to be able to put them in there.

And there’s one pair that are my oldest and probably most valuable shoes. They are “straights” — there’s no difference between left and right. And they’re embroidered with dyed straw and decorated with metallic threads and lace. I thought originally these were from around the 1830s, but the heels make me think they’re a little bit later, so around the 1850s.

Hand-made shoes, then?

Shoemaking was a really easy industry to have at home. You didn’t need a lot of expensive materials or a lot of square footage. Until the advent of the factories, people would make shoes for their families or the smaller local community. So those could very well have been produced in a small home.

With decorations including straw embroidery, these 19th-century shoes from Christine McDowell’s collection are among her favorites. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

You can find patterns in 19th-century women’s magazines, like Peterson’s Magazine, for slippers and embroidery designs. You could conceivably embroider something to bring to a cobbler for working into a shoe. Or with a soft-enough sole, it would be something a women could sew herself, like slippers for her husband. I’ve seen many, many patterns for crewelwork or petit point, things like that, to make men’s slippers as gifts.

Tell us about the Wall of Shoes.

Kirstin Koepnick ’21 and Jason Ross ‘19 helped me assemble this, along with Aidan McDowell, the assistant technical director in the theater department, who happens to be my nephew. I designed it, he and I engineered it, and then the four of us — it was like a barn-raising, because it was really complicated to get this minimalist object to stand freely in the space.

The Wall just celebrates aesthetically pleasing, interesting shoes from the 20th century. I think all but one of the shoes there are mine. You know, people are always sending you things that are relevant to your industry. So, some of these shoes people actually gave me.

And I also happen to have really small feet [McDowell laughs], which has proved advantageous, because people are like, “I can’t wear these, you can have them.” So small feet and a particular interest have proven to be really beneficial.