A lot of what we know, or think we know, about archaeology comes from movies like Raiders of the Lost Ark: Indiana Jones racing Forrestal or Belloq to discover the next cool thing.

Hollywood aside, there’s truth to that depiction, says Kristen Barnett, assistant professor of American studies at Bates. “Really, most archaeology is still about things.”

But here’s the thing.

Artifacts are often in “close proximity to living communities — people today,” explains Barnett. Despite that proximity, archaeologists have, say critics, long run roughshod over indigenous communities — the places where such artifacts truly belong — with generations of scholars “making a living conducting research on Native Americans’ lifeways, bodies, and sacred places,” in the words of scholar Sonya Atalay.

Kristen Barnett and her students walk along the shore near the Old Togiak excavation site on May 15, 2019. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

Barnett’s method, one that’s now playing out in a small village along the southwest coast of Alaska, tries to address such inequities in archaeological practice with an approach that emphasizes partnership, sharing, and engagement with Indigenous communities.

It’s called indigenous archaeology because it “places the needs of the community at the center,” she says.

Flipping the script, indigenous archaeology moves away from notions of discovery, which can imply seizing ownership. As Barnett says to her students, “We’re not really discovering anything. We’re serving.”

Indigenous archaeology “places the needs of the community at the center,” says Assistant Professor of American Studies Kristen Barnett. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

Specifically, Barnett and her students are serving the small Alaskan village of Togiak, or Tuyuryaq in the native Yup’ik language. Located about 390 miles south-southwest of Anchorage, the coastal village is accessible only by water or air. It numbers about 800 residents, of whom about 85 percent are Yup’ik.

Barnett herself is an Alaska Native, a member of the Unangax (or Aleut) people of the Aleutian Islands and coastal mainland. She has described Togiak as “kind of a cousin village.”

Funded by a major National Science Foundation grant, Barnett has thrice brought a team of Bates students to the Togiak area, most recently during Short Term last May.

As with past Bates trips, the students’ work had a twofold quality. First, they spent a week in the village, engaging with students at the local K–12 school and meeting community elders.

Then they decamped across Bristol Bay — just about a mile and a half as the crow flies — to do archaeology at Old Togiak, the village’s location until about a century ago, before inhabitants began crossing the bay to resettle at the site of today’s village.

As an archaeological site, Old Togiak has been impacted: an operational cannery, the North Pacific Seafoods Cannery and Fish Processing Plant, sits atop a portion of the old village site.

The Bates excavation site is located at Old Togiak, located across Bristol Bay from Togiak. A cannery sits atop a portion of the old village site. (Google Earth)

After two weeks of fieldwork at Old Togiak, the Bates group — comprising Barnett, 11 students, and two research assistants, Elliot Chalfin-Smith ’21 and alumna Kelsey Schober ’16 — returned to Togiak for another brief stay, including attending the school’s prom.

Midway through their Togiak fieldwork, Tim Leach ’99 joined the group for a couple days of photography and interviews. He came away with these 11 words that explain the Bates students’ experiences and insights.

‘Mind-blowing’

A prospective biology major, Emma Christman ’22 is a Mainer who grew up near Bates in Litchfield. With most of her first Bates year behind her, Christman felt some wanderlust. “I needed to get out for a little bit. Plus, I’d never been on a plane.”

The course introduced her to big ideas now facing the field of archaeology. “Some of the big ethical and moral questions that come up in indigenous archaeology and community-based research I had never even heard of,” she says. “It was mind-blowing to walk into this field and be like, ‘holy’…This is a whole new world.”

‘Narrative’

Solaine Carter ’21 of Tucson, Ariz., was drawn to the course by her major: rhetoric, film, and screen studies. “I’m really interested in narratives and storytelling,” she says.

In terms of indigenous archaeology at Togiak, she’s interested in “what it means, what it can look like, and what it should look like. That’s where the rhetoric piece comes in for me.”

When talking about her interest in the course, Nell Pearson ’20, an anthropology major from Brooklyn, N.Y., references a famous TED talk by Nigerian author Chimamanda Adichie, “The Danger of the Single Story,” who argues that it is “impossible to engage properly with a place or a person without engaging with all of the stories of that place and that person.”

On the beach, Nell Pearson ’20 prepares to screen dirt excavated from the Old Togiak dig. Screening ensures that no artifacts are missed. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

The village of Togiak knows the dangers of the single story because it’s been the victim of at least one.

In the 1960s, a doctoral student briefly explored Old Togiak and removed thousands of items, including human remains that Barnett, several years ago, helped to repatriate. In his dissertation, the doctoral student dismissed the site as a midden, a dump for domestic trash — a single story later proven wrong.

“With Professor Barnett coming here, we can see if the narrative is a little bit more complex than just one definition of a place,” says Pearson. “That’s cool to be a part of.”

‘Continuity’

Now, Barnett is challenging current thinking about Togiak and other regional models, specifically that the site was occupied by one group of people during the Medieval Warm Period, circa 950 to 1250, and then, when the Little Ice Age arrived later, “there was a total replacement of that population.”

At the dig, Jinzhi Wei ’20 (right) talks with Kristen Barnett about an object that was revealed at the site. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

Emphasizing disruption, such a theory can have “severe” implications for an Indigenous community by severing the community from its own past — “from its own story,” Barnett says.

As is typical of pre-colonial Yup’ik dwellings, the ones at Old Togiak are partially below ground. There are larger community houses for men’s work and activities, known as qasgi, and smaller sod houses, about 4 meters in diameter, for women, known as ena.

In looking at the concept of “cultural continuity” at Togiak, Barnett is zeroing in on how women ran and organized their households in the ena. For her, “ideas about cultural continuity are really wrapped up in those small homes.”

The Bates campsite at Old Togiak. From left, an ATV and cart; wooden shack used as the camp kitchen; the shipping container fitted with six bunks; Barnett’s tent atop the container; and another tent and WeatherPort nearby. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

While some things might change in a village over time — such as architecture, population, and what villagers ate — what might not change, and therefore might be a better indicator of continuity, is the operation of households.

“We all have a mental roadmap of what it means to make a home,” explains Barnett. “For instance, no matter where I live, I’ll put my keys in the same spot.” All those routines create “a roadmap of what my home means and how it’s organized.” At Old Togiak, a consistent household roadmap could be key to supporting ideas of cultural continuity over hundreds of years.

Of course, if the evidence ultimately shows a population change at Old Togiak, “you don’t ignore it,” Barnett says.

But, either way, “the archaeological framework needs to be expanded to consider local perspectives and insights and to work through the process together. The archaeologist is working with materiality, whereas a community might be working with thousands of generations of knowledge and experience.”

Having breakfast inside the camp WeatherPort are, from left, Anna Truman-Wyss ’21, Hannah Webster ’22, Emma Christman ’22, and Solaine Carter ’21. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

Speaking of the Little Ice Age: Barnett, pointing to research from University College London, notes that this period of global cooling in the 16th and 17th centuries may have been brought on by the genocide of millions of Native peoples in the Americas beginning in the 15th century. The resulting revegetation of land previously occupied by humans soaked up enough atmospheric carbon dioxide to cool the planet.

‘Ownership’

Indigenous archaeology has “a lot to do with power dynamics,” says Jinzhi Wei ’20, a religious studies and economics double major from Liuzhou, China.

In that sense, Barnett “doesn’t claim ownership of the project, and she doesn’t prioritize the needs of archaeology over the needs of the community. She’s helping the community trace back its cultural past.”

‘Soothing’

At the dig site, students had two primary jobs, one inside the 10-by-20 WeatherPort canopy that covered the dig, and one outside.

Inside, students carefully excavated soil with trowels, placing any found objects into plastic bags for labeling and logging.

Outside the Weatherport, students screened excavated soil for smaller items missed by the inside team.

During the screening process, Maya McDonough ’22 winces and mud splashes as Jinzhi Wei ’20 pours water onto excavated soil. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

Eventually, the work gets even tinier. The soil will undergo geochemical analysis as well as “flotation” to separate light from heavy particles and, in so doing, identify plant remains.

Inside the WeatherPort, a grid marked 1-meter squares that are typical for a dig site. For students new to excavation with a trowel, “one meter is huge,” says Barnett, so she further divided the meter squares into smaller, more manageable 50-centimeter quads.

Anna Truman-Wyss ’21, an American studies and anthropology double major from Auburn, Ala., preferred the slow, steady, and mindful process of excavation.

“Excavating is soothing,” she says (even though she feels that she’s “not good at it”).

Mindful that fieldwork is, well, work, Kristen Barnett scheduled fun, too, like Hat Night, where students created hats from found items. Here, Eliot Chalfin-Smith ’21 (left) presents a chocolate prize to Ian Christiansen ’22. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

The process of screening excavated dirt, on the other hand, is “sitting around waiting for more soil, and then you go-go-go, and then you sit around again. I like the consistent work of excavating.”

‘Grundén’

To do this type of fieldwork, you have to be equipped both intellectually and otherwise, with gear that’s right for days and days of outdoor work in breezy, cool (highs in the 40s, lows around freezing), and sometimes wet weather.

What Bean boots are to students on the Bates campus, Grundéns outerwear, especially bib overalls, was to the students on the Togiak trip. “We learned to love them,” says Maya McDonough ’22, a prospective geology major from Aspen, Colo.

At first, “everyone was like, ‘They’re so ugly and bulky.’ But they keep you dry and they keep you warm — and mostly clean.”

‘Respect’

For Joseph Willky ’20, a double major in American studies and anthropology from Randolph, Mass., the guiding concept behind indigenous archaeology is respect.

What L.L.Bean boots are to the Bates campus, Grundéns outerwear was to students in Togiak. Near midnight on May 15, Ian Christiansen ’22 holds rocks that he collected off the beach for skipping into Bristol Bay. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

“We follow the values that Togiak stands by,” he says. Whether it’s archaeology, or land use, or “things that might not be seen as sacred,” like pieces of wood that float onto shore near their campsite, “it all falls under respect. We are the visitors.”

Barnett, he says, tries to instill humility in her students. “You cannot take whatever privilege that you were born with and automatically place it into a new place. That does not cut it.”

‘Weather’

The absence of distractions caused by things like cell phones meant that the Bates students began to pay greater attention to the weather, as does anyone who works outdoors.

As the team prepares to depart Old Togiak, students cover the site with tarps and hay, applied here by Joseph Willky ’20 (left) and Emma Christman ’22 (second from right), to shield it from the elements. (Courtesy Kristen Barnett)

Asked what surprised her on the trip, Hannah Webster ’22 of Shelburne, Vt., seemed abashed by her answer. “This might be generic, but it’s the weather.”

The mornings, she described, “have been kind of like cloudy. It’s been a little bit rainy at night. Then we wake up, and I expect to see rain, but all of a sudden the sky opens and it’s a beautiful blue sky.”

Then there were the two days of rain and wind that threatened to blow away a tent at the campsite until they created a wind block.

Trowel in hand, Hannah Webster ’22 excavates soil at the Old Togiak site on May 15. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

“We had to have people standing against the tent to hold it up and build a wind block in the pouring rain. Those moments were really challenging,” she says.

“But looking back, it was also really exciting — kind of fun, in a way. It was a different kind of fun.”

‘Box’

During their visit, the students witnessed the delivery of a small wooden box, labeled “fragile,” to Barnett.

The box contained human remains looted from Old Togiak in the 1990s. During prosecution of the crime, the remains were held as evidence, then boxed and delivered to the Traditional Council of a nearby village, Twin Hills.

There they sat for years. Complicating and delaying repatriation was the transfer, from Twin Hills to Togiak, of the rights to the land from which the remains had been looted.

While some archaeologists work with or research human remains, Barnett doesn’t. Still, there was the box, so she informed Togiak’s Traditional Council and made arrangements to return them to the village.

During the Bates stay, a box containing human remains, looted from Old Togiak years before, was delivered to Barnett. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

In such communications with the council, she is mindful of her role. “My goal is not to burden, but be of service. So, if I’m like, ‘I’ve got this, and what are you going to do now?’ — that approach can become really burdensome.”

The remains were returned to the community. Any decisions regarding their treatment and care rest with the community, Barnett says.

‘Instagram’

None of the students had cell service in Togiak, and that suited them just fine.

“I don’t know where my phone is right now,” said Jack Johnson ’22 of Brewster, Mass. “It’s refreshing. You realize all the things that you don’t need at all. You don’t need to go to Instagram, Snapchat, and all that stuff. It’s just fluff.”

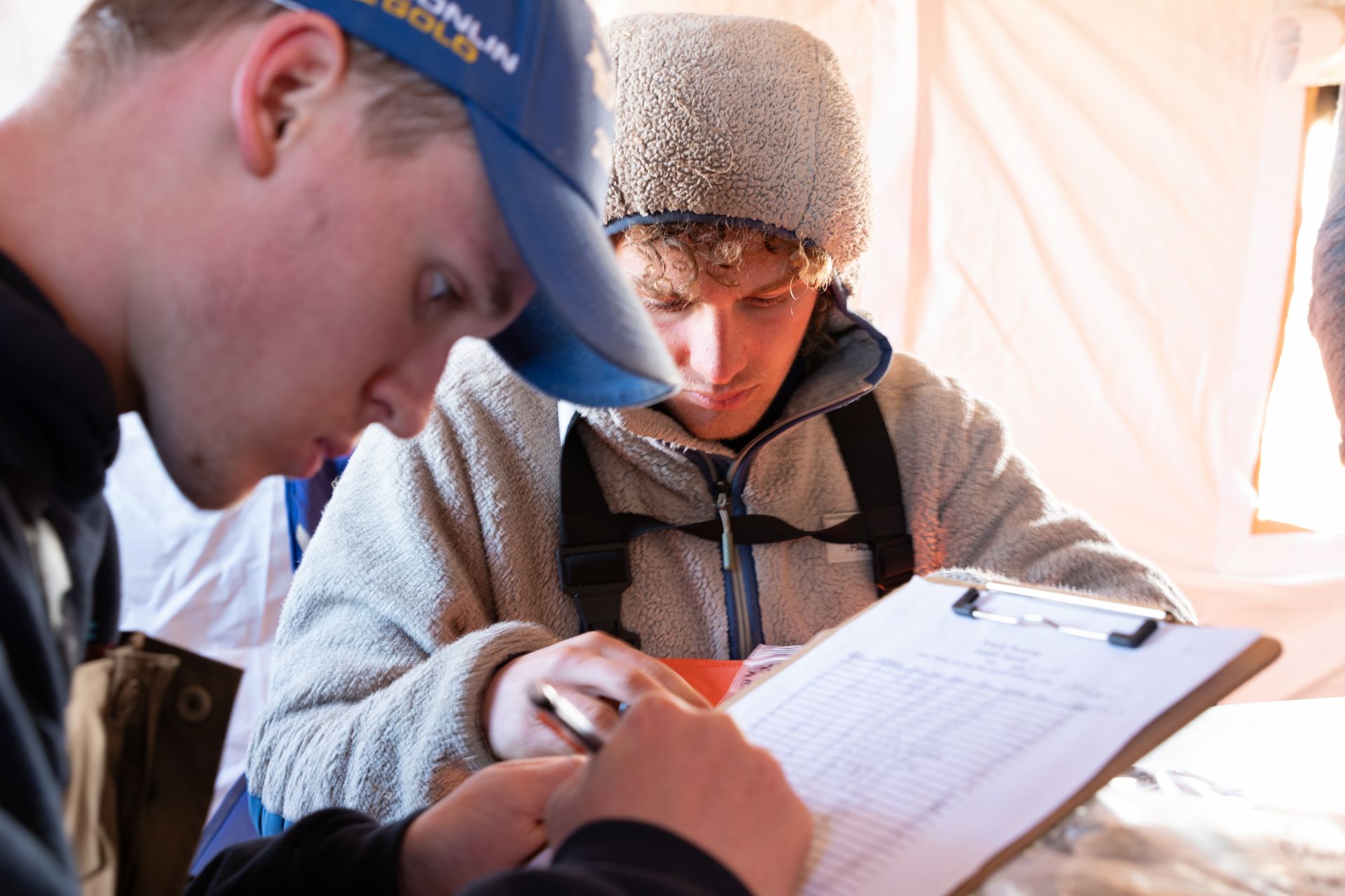

At the end of the workday on May 15, Kyle Jorgensen ’22 and Jack Johnson ’22 conduct check-in to ensure all samples and artifacts are accounted for. (Tim Leach ’99 for Bates College)

Kyle Jorgensen ’22 of Lawrence Township, N.J., agrees. “Away from the phone, I feel that I can absorb more of where I am and what I’m doing. It’s kind of like you have more purpose.”

‘Awesome’

“Awesome” is perhaps overused, but apropos when you’re surrounded by snow-covered peaks on three sides, the Pacific Ocean on the fourth, and blue skies above.

For Ian Christiansen ’22, a prospective physics major from Hudson, N.H., an awesome moment occurred when clouds and rain shrouded everything, during what’s become an annual tradition for Barnett’s students and local schoolchildren: a climb up Two Hill, a small rise near town not much higher than Mount David.

“It wasn’t pouring, but it was rainy, cold, and damp. But it was an awesome bonding experience,” Christiansen says. “We were all chugging through it together.”

Anna Truman-Wyss ’21 (left) and Skylar Wassillie, a student from Togiak School, walk together during the annual climb up Two Hill near the village. (Courtesy Kristen Barnett)