Sin taxes — levies on consumer products deemed harmful like alcohol or tobacco— have a history of creating unintended consequences, if not backfiring altogether.

When Minnesota raised excise taxes on cigarettes in the last decade, for example, it caused a spike in black-market smuggling.

Now you can add another item to the tax-and-consequences list: vaping products.

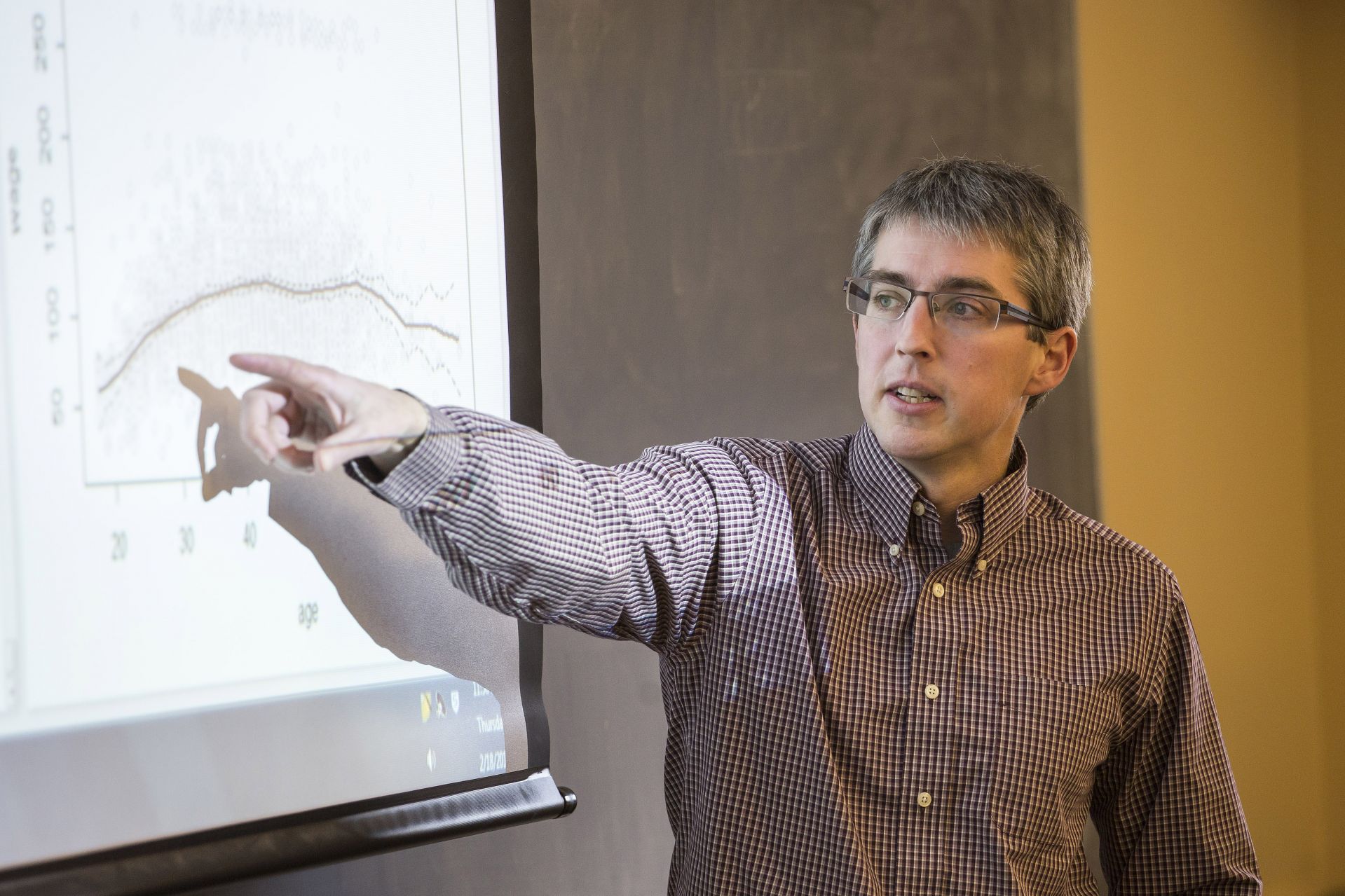

Associate Professor of Economics Nathan Tefft is one of six authors of a new study that finds that raising taxes on e-cigarettes in an attempt to cut vaping may have the unintended and dangerous consequence of increasing consumption of conventional — and many would say far more deadly — tobacco cigarettes.

Funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, the study, “The Effects of E-Cigarette Taxes on E-Cigarette Prices and Consumption: Evidence from Retail Panel Data,” was published Feb. 10 by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

A new study finds the “potential for e-cigarette taxes to induce some vapers to increase traditional cigarette smoking while vaping less,” says Associate Professor of Economics Nathan Tefft, seen in class in February 2016. (Josh Kuckens/Bates College)

The study finds “the potential for e-cigarette taxes to induce some vapers to increase traditional cigarette smoking while vaping less,” Tefft, an expert in the intersection between consumer behavior and public policy, said in an interview with communications specialist Carmen Price at Montana State University, where he is a visiting research scholar.

When the price of vaping goes up, consumers will switch to cigarettes.

The study finds that for every 10% increase in e-cigarette prices, e-cigarette sales drop 26% while causing sales of conventional cigarettes to rise by 11%.

Put another way, for every e-cigarette pod (0.7 ml of liquid nicotine) not purchased as a result of an e-cigarette tax, consumers will buy 6.2 extra packs of regular cigarettes, according to simulations conducted by the researchers.

In economic terms, this means that e-cigarettes are “elastic” goods: Consumer demand will substantially change when prices change. Also, e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes are economic substitutes for one another, so when the price of vaping goes up, consumers will switch to cigarettes.

To arrive at their findings, the researchers examined Nielsen Retail Scanner data from about 35,000 U.S. retailers from 2011 to 2017.

Nearly 3% of U.S. adults used e-cigarettes in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with growth in use by adolescents especially rapid: Almost 27.5% of high school students used e-cigarettes in 2019.

“Because smoking is known to have substantial negative health impacts,” Tefft added, “policymakers should be aware of this potential tradeoff when contemplating e-cigarette control policies.”

Twenty states (including Maine) and the District of Columbia now tax vaping products, and Congress is contemplating a federal tax.

While vaping-related illnesses are a public health concern, conventional cigarettes kill nearly 480,000 Americans each year, according to CDC data.

Tefft is spending the 2019–20 academic year at MSU conducting research focused on risky health behaviors and health policy.