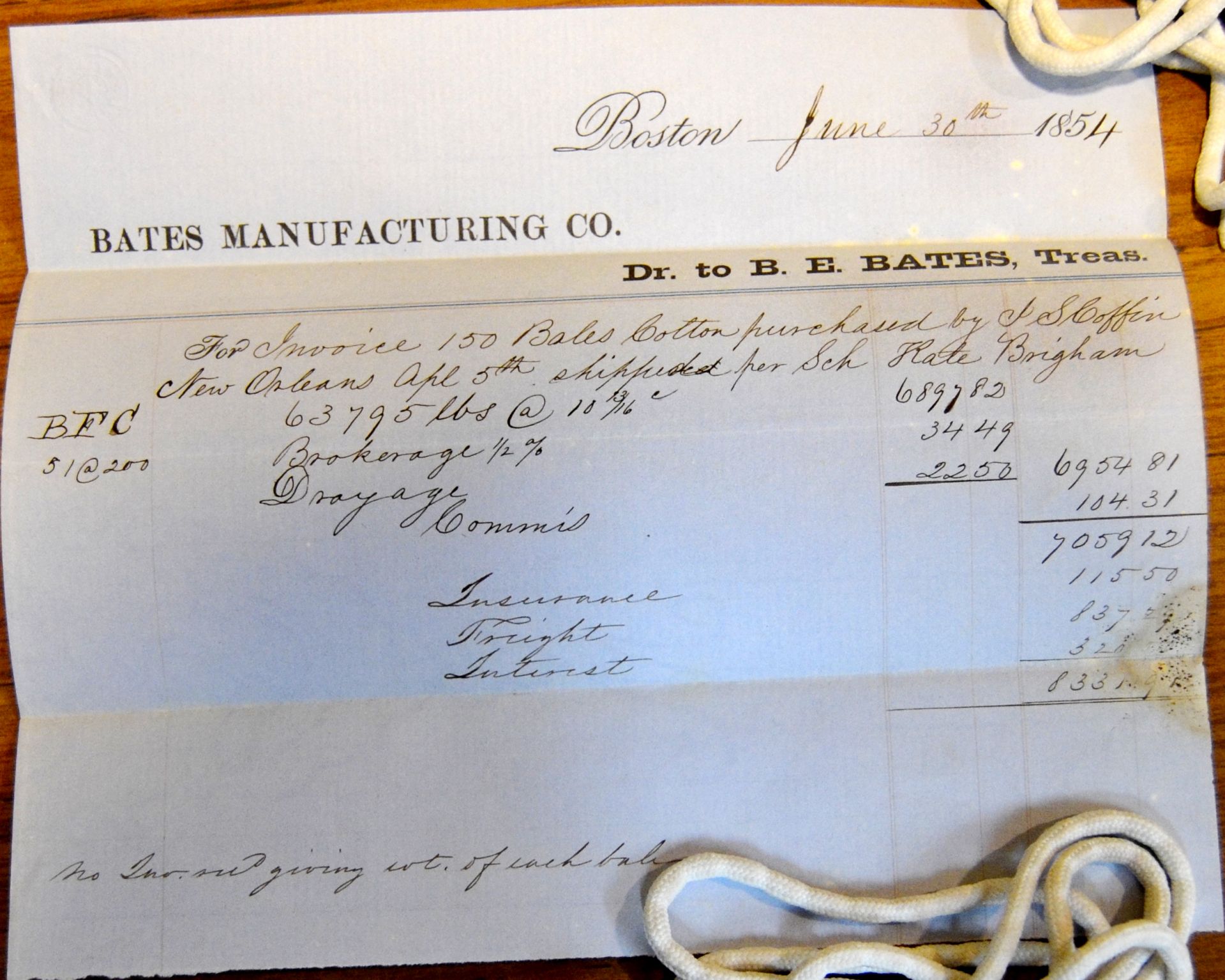

In April 1854, a three-masted schooner, the Kate Brigham, set sail from New Orleans loaded with 150 bales of cotton grown by slaves on Southern plantations.

The cotton shipment was one of many destined for Lewiston, Maine, a small but growing mill town where entrepreneur Benjamin Bates of Boston and his fellow investors had built their first textile mill two years earlier. In its first year, the mill had netted $33,000 in profit — putting Benjamin Bates on track to become a wealthy man in the years before the Civil War.

Bates readers know what comes next. Benjamin Bates and his business associates, eager to create civic institutions in Lewiston, made financial gifts to a new school founded in 1855 by Oren Cheney, a Freewill Baptist leader and fervent abolitionist. A decade later, Cheney named the school, by then a college, after Bates, its principal benefactor.

Eager to build civic institutions in the growing town of Lewiston, textile mill owner Benjamin Bates and his associates — wealthy thanks to slave-grown cotton — made financial gifts to the school that would become Bates College.

And from that foundation grew a college that today is rightly and widely known for its inclusive character.

That founding story is familiar, but it’s not the whole story, say Bates faculty and students who are now doing academic research to better understand what it means that a Northern college like Bates was intertwined at its founding with an American economy fueled by slave labor.

“Everyone says, ‘Bates was founded by abolitionists,’” says Perla Figuereo ’21 of the Bronx, N.Y., who was part of a digital humanities course last fall that has begun a long-term, data-driven exploration of Bates’ early financial history. “But no one adds, ‘and funded by slave cotton.’”

The founded-by-abolitionists narrative is “not necessarily false, but rather incomplete,” senior history major Ursula Rall of Kent, Ohio, told her audience during a Martin Luther King Jr. Day presentation with fellow senior Emma Soler of Bethesda, Md. “It’s important to acknowledge the other part of the founding.”

To be sure, up to the time of the Civil War, there’s hardly an American institution that wasn’t supported by the American slave economy.

![African Americans, possibly slaves, pick cotton near Montgomery, Ala., in 1860, (Lakin, J. H, photographer. [186] https://www.loc.gov/item/2012648057/0](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2020/02/1s02973u.jpg)

In this 1860 photograph, African Americans, likely slaves, pick cotton near Montgomery, Ala. (Lakin, J.H., photographer. 186: https://www.loc.gov/item/2012648057)

“Slavery was integral to our nation’s founding, our economy in the North and South, our universities, and our wealth,” says journalist and Bates history major Kristen Doerer ’14, who has reported for the Chronicle of Higher Education on how colleges have reckoned with their historical connections to the U.S. slave economy.

“We can’t kid ourselves and think that because Bates is in the North and was founded by abolitionists that it was immune from slavery,” she adds. “If we view wealth from cotton and slavery as dirty money, we should know that the dirt is everywhere — even under abolitionists’ fingernails.”

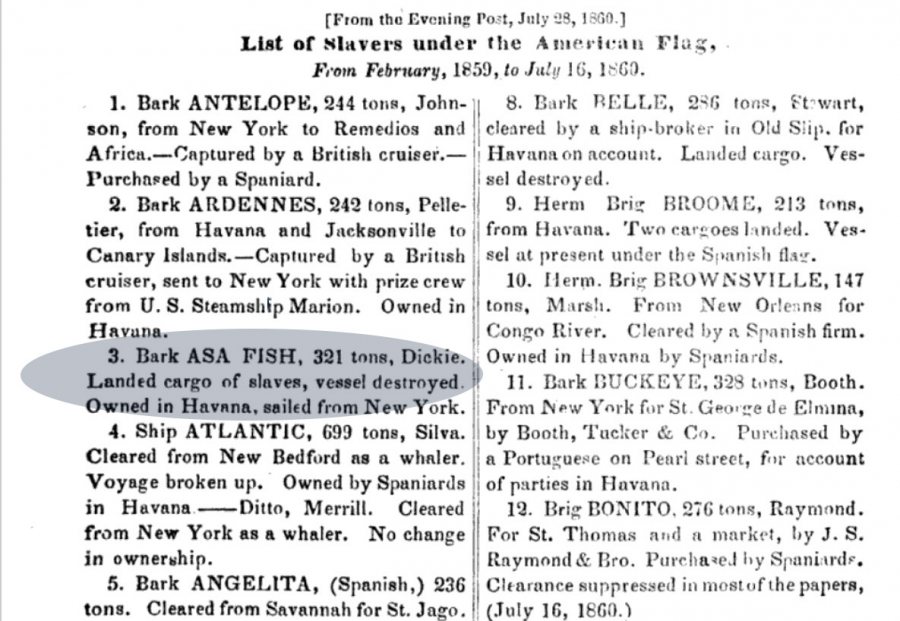

To that point, one day after Rall and Soler’s MLK Day presentation at Bates, Maine Public Broadcasting devoted a segment of its Maine Calling program to examining the connections between the slave economy and Maine’s vaunted maritime industry, specifically how various Maine ship captains transported slaves from Africa to North America in the 1800s, even after it was made illegal.

That’s a barely known fact, says Kate McMahon, a scholar and Maine native who has done extensive research on Maine’s connection to the slave trade, because Maine has “valorized” its maritime tradition over the years while “making the suffering of other people invisible.”

“Slavery was integral to our nation’s founding, our economy in the North and South, our universities, and our wealth,” says journalist and Bates history major Kristen Doerer ’14, seen during a campus visit in 2019 when she offered a public talk and met with history students. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

If we fail to fully appreciate this local history — such as, she says, the existence of “buildings in Portland that were built from funds from selling enslaved people” — then how do “we even begin to understand that we actually live with the legacies of slavery every single day here and now?”

On a larger journalistic scale, there’s also the ongoing New York Times’ 1619 Project, named for the year African slaves first arrived in Virginia. That project seeks to place “the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.”

The digital humanities course that Perla Figuereo took last fall is taught by Anelise Hanson Shrout, an assistant professor of digital and computational studies. Like her students, Shrout feels the imperative to flesh out the college’s founding story.

“For me, as a historian and as a human who lives in Lewiston and works at Bates, the story is more complicated than ‘Bates has always stood for abolition,’” Shrout says. “We have the same foundational American sin baked into our history that much of the U.S. does.”

Perla Figuereo ’21 (center) presents a digital project developed with, to her left, classmate Alya Yousuf ’21 as part of their fall 2019 coursework in “Data Cultures,” taught by Assistant Professor of Digital and Computational Studies Anelise Hanson Shrout. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Last fall, Shrout’s students began painstaking work to review and pull numbers from the college’s early business ledgers, held by the college’s Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library. Those ledgers record the donations, large and small, that Cheney took in, including gifts from Benjamin Bates, who gave approximately $175,000 to the college, equivalent to a few million dollars today.

They also began a review of the many bundles of Bates Mill cotton invoices now held by Lewiston Public Library. It is slow work, says Shrout, who anticipates devoting future editions of her course to the project. “We’ve only scratched the surface.”

Still, the individual cotton invoices are fascinating. Besides the amount and cost of the cotton shipments, they include dates, ship names, shipping routes, and wholesalers, painting a picture of how antebellum cotton made its way north.

Besides the aforementioned Kate Brigham, another ship that transported cotton to the Bates Mill was the Paul Boggs, which ran aground on Cape Cod’s infamous Chatham bar two years later. And still another, the Asa Fish, built in Mystic, Conn., in 1849, also transported African slaves to Cuba.

Shrout says the process of creating meaning from handwritten cotton invoices promises to teach a powerful liberal arts lesson. “One of the questions we’re asking is, ‘What does it mean to produce a dataset that represents labor that was violently stolen from people?’ How do we do that ethically and thoughtfully?”

Dated June 30, 1854, this invoice for 150 bales of cotton (63,795 pounds), for delivery to the Bates Manufacturing Co. and its treasurer, Benjamin Bates, indicates that the cotton was shipped from New Orleans on the schooner Kate Brigham. (Photograph by Anelise Hanson Shrout)

In today’s world, “data is thrown around as if it is objective,” Shrout continues. “We feed tremendous amounts of data into algorithms that decide what a self-driving car sees as human or how people are policed. But data is always an artifact of some kind of human decision, so at a meta level in this class, I want students to take that away.”

The basic facts of the college’s founding, both Benjamin Bates’ cotton connection and Oren Cheney’s abolitionist views, have been well-documented over the years, even as the latter narrative has, until now, received more attention.

In the 1970s, Jim Leamon ’55, then a young history professor and now an emeritus member of the faculty, enlisted students to help him research Lewiston’s economic history, including Benjamin Bates’ contributions to the city’s early growth.

Commissioned by the city’s Historic Commission, Leamon’s monograph explained why Benjamin Bates’ mills prospered during the Civil War as other New England mills suffered: because Benjamin Bates gambled on a long war and “bought up huge stocks of cotton at 12 cents a pound when the struggle began,” writes Leamon. “By 1864 cotton was worth 70 cents, and a year later it was over a dollar a pound.”

The Asa Fish was among the many ships that delivered slave-grown cotton to Benjamin Bates’ mills in Lewiston before the Civil War. Flying under the American flag, the bark also transported slaves from the west coast of Africa to Cuba.

Thanks to the stockpiled cotton and government war contracts, Lewiston mill profits were “remarkable” during the war, Leamon concludes. In sharp contrast, other New England mills sold their stockpiled cotton early in the war for a quick profit, then had to pay exorbitant prices as the supply of Southern cotton dried up. In Lowell, Mass., for example, the era is dubbed “Lowell’s blunder.”

It is important to note, too, that Benjamin Bates was among a group of businessmen who lent their support to the new school, including Francis Skinner, a Boston-based middleman who sold Southern cotton to Benjamin Bates’ mills and who became a college trustee.

“We hate it — we abhor it, we loathe it — we detest and despise it as a giant sin against God, and an awful crime upon man.”

Oren Cheney’s devotion both to abolitionism and to creating a radically inclusive college have also been well-documented over the years, including by Tim Larson ’05 in his landmark senior honors thesis in history, “Faith By Their Works.”

Noting that Cheney had operated a branch of the Underground Railroad in Maine prior to founding a new college, Larson quotes Cheney’s own words on the topic of slavery: “We hate it — we abhor it, we loathe it — we detest and despise it as a giant sin against God, and an awful crime upon man.”

Larson also notes that, in founding an inclusive college, Cheney was combatting powerful social norms that “advocated for discrimination against women, African Americans, and the poor.” Despite those and other pressures, the college “held its ground” and maintained its inclusive practices.

(In fact, Bates College wasn’t Cheney’s only handiwork. Well-connected politically thanks to his service in the Maine Legislature, Cheney used his influence to help found another mission-driven school, Storer College, in Harpers Ferry, W. Va., in 1865, which was dedicated to educating freed slaves.)

Still, Larson noted, there was the vexing question, a “contradiction” as he called it, of why an “ardent abolitionist” like Cheney would take money from industrialists like Benjamin Bates, who might be “as much to blame as Southern slave owners” for “allowing slavery to thrive.” Larson answers the question this way: “Perhaps this contradiction speaks more to the omnipresence of the slave system in American economy than to Cheney’s own shortcomings.”

Founder of Bates College Oren Cheney, seen in 1873, was a bona fide abolitionist. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Fifteen years later, appreciating the urgency with which Bates students and faculty have taken up “the contradiction” requires some historical context.

In 2003, Brown University started to investigate its direct historical connection to slavery and the transatlantic slave trade. A few years later, scholars and students at Harvard began a similar exploration. And in 2013, historian Craig Steven Wilder published Ebony and Ivy, which broadly explained how all of U.S. higher education in the 18th and 19th centuries, not just a few schools, capitalized in some way on America’s slave economy.

With Wilder’s book, explains Joseph Hall, an associate professor of history at Bates, “U.S. colleges no longer had to choose” whether to admit to benefiting from slavery. “Wilder demonstrated that everyone was involved, whether you liked it or not.”

In addition, a new generation of scholars, including Wilder, from groups previously underrepresented in academe, including women and African Americans, are now asking new questions about American history, often through the lenses of colonialism (the subjugation of one people by and for the benefit of other people), white supremacy, and racism.

“People are asking different kinds of questions,” says Hall. “And different people are involved in asking those questions.”

In the early 2000s at Bates, questions about the college’s historical connection to the American slave economy were cropping up in and around Bates classrooms, prompted by faculty in the history department and the Africana program, including professors Sue Houchins and now-retired Margaret Creighton. (Discussions in her classroom, in part, led to Larson’s Bates-focused thesis.)

In recent years, faculty and students began to move the topic front and center in their academic work, spurred in part by national events, including publication of Ebony and Ivy, racial violence in Ferguson, and the subsequent emergence of Black Lives Matter. At the same time, Bates was using its convening power to showcase a string of prominent speakers on race and equity in America, including Wilder himself, who spoke at Bates in January 2017.

An audience fills a Dana Chemistry Hall classroom on Martin Luther King Jr. Day to hear Emma Soler ’20 and Ursula Rall ’20 lead a discussion about the college’s dual founding narratives: founded by abolitionists and funded initially by Benjamin Bates, a textile manufacturer who derived wealth from slave-grown cotton. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

That September, members of the Bates faculty raised the issue during a discussion in a packed Pettengill Hall classroom, held to help students understand issues of white supremacy and Confederate monuments in the wake of violence in Charlottesville, Va.

Noting how Benjamin Bates profited from slave-grown cotton, Assistant Professor of History Andrew Baker pointed out that while it’s meaningful to remove Confederate monuments in the South, we need to look at history closer to home. Racial problems don’t somehow “belong to a different time,” Baker said. “It’s always been a part of America itself, and so that touches all of us.”

From the classroom to the public lectern, Joe Hall has lent his academic voice to the topic in recent years. He recalls how, more than a decade ago and after Larson did his thesis, he began to mention the college’s connection to slave-grown cotton as a “throwaway line” in one of his classes, such as “African Slavery in the Americas.” He says, “I remember a student telling me, ‘I never thought about that before.’ It’s been kind of an itch” ever since.

From the classroom and the lectern, Associate Professor of History Joe Hall in recent years has invited the Bates community to consider the meaning of its founding connection to the American slave economy. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In spring 2018, Hall introduced the topic in a “master class” that he led during a campus Admitted Students Reception, when Bates rolls out the garnet carpet for new admits. After briefing the students on the basic facts, he asked, “What’s missing from the story about Oren Cheney and Benjamin Bates?” One of the students replied, “There’s no African American history here.”

Hall says, “That was great, because he was absolutely right.”

And that September, Hall, speaking to the incoming Class of 2022 during Opening Convocation, used his address, “Questions for Bates,” to explore at some length the apparent contradictions of Bates’ founding.

For the past two semesters, Hall has devoted one of the department’s signature courses, “Historical Methods,” an upper-level seminar that prepares majors for thesis work, to the question of Bates’ founding. During the course, he has guided students into the college’s Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library and downtown to Lewiston Public Library.

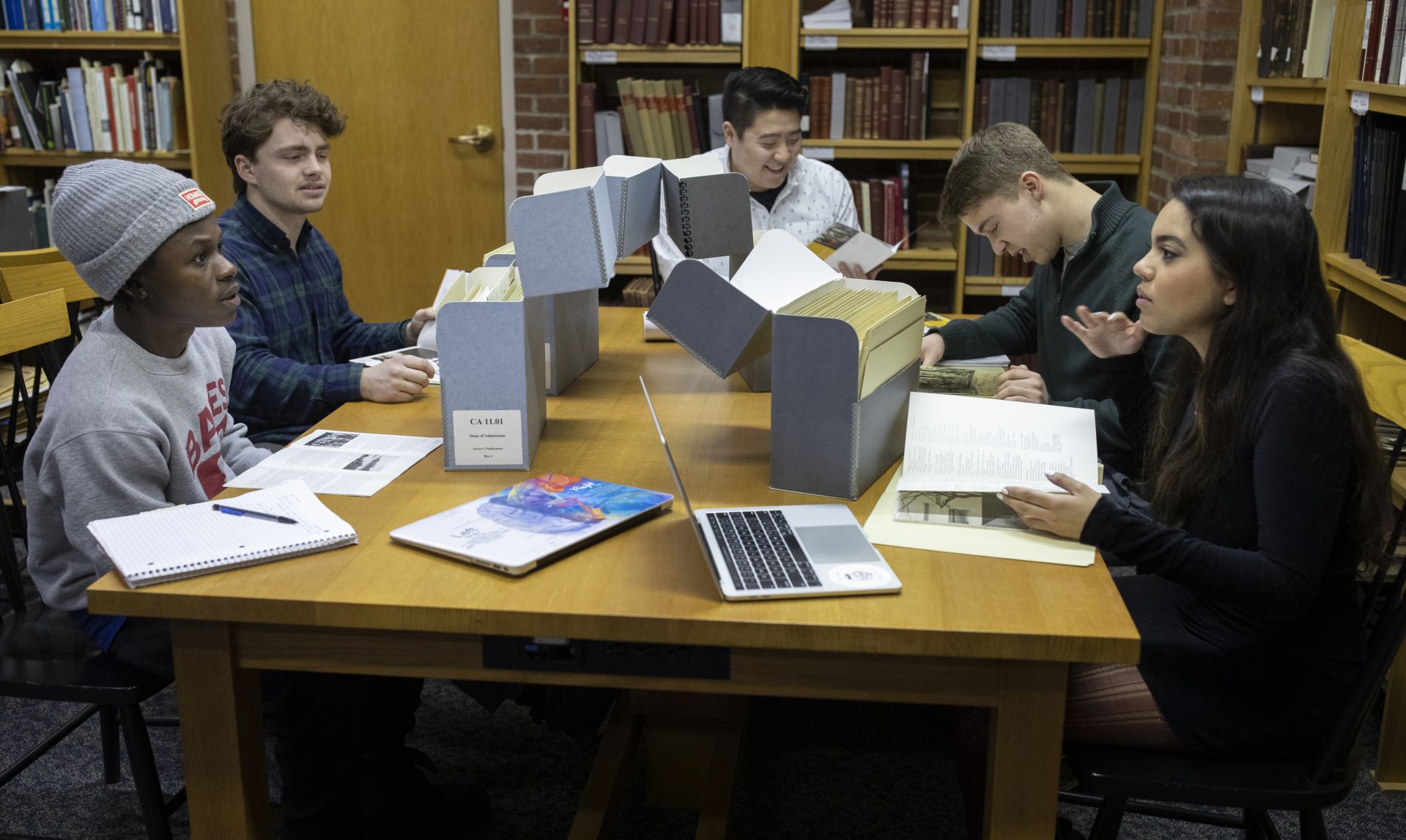

In February 2019, students in Associate Professor of History Joe Hall’s historical methods class pore over historical documents related to Bates’ founding in Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library. From left, Eric Opoku, Benni McComish, Zach Jonas, Andrew Faciano, and Ke’ala Brosseau. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

From Hall’s perspective as a teacher and scholar, probing questions about Bates’ founding are what a liberal arts education is all about: appreciating complexity, knowing that there’s more than meets the eye, and being on the lookout for unintended consequences.

“The good in the world, even the good found in a place like Bates College, does not come without a cost,” he says. “In the case of Bates’ founding, it was a tremendous cost in human lives.” And it’s powerful, he adds, that his students are learning these lessons in a Bates framework. “There’s immediacy. They can see the relevance of it because they care about Bates.”

Ke’ala Brosseau ’20 of South Burlington, Vt., was in Hall’s methods course last year. With several classmates, she made a presentation at the annual Mount David Summit that looked at how Bates, as an institution, has foregrounded its abolitionist founding narrative over the years.

When an institution emphasizes one narrative, it’s like putting on blinders. “You don’t recognize the imbalances of power,” she says, that have muted other voices over time, including, in the case of Bates’ founding, humans imprisoned by slavery. Furthermore, she adds, “It’s hard to recognize inequality today when we don’t confront things that have happened in our past.”

“It’s hard to recognize inequality today when we don’t confront things that have happened in our past,” says history major Ke’ala Brosseau ’20 of South Burlington, Vt. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

To be sure, it will take time and effort to discover, let alone amplify, the voices of people who grew the cotton that created the wealth leading to the college’s founding.

For her senior honors thesis, Emma Soler initially hoped to “put a human face” on the cotton trade by tracing cotton that Benjamin Bates used in Lewiston back to specific Southern plantations, and perhaps to specific individuals.

In the limited time of a senior thesis project, that goal proved unattainable. Indeed, Hall imagines that the search for cotton clues might someday extend to century-old dissertations on the cotton trade housed in Southern universities. “It will take some bibliographic digging,” he says.

So Soler has pivoted to a broader analysis, looking at Bates’ founding in the context of the U.S. slave economy as well as campus discourse around the issue, contemporary campus culture, and reparations movements.

Emma Soler ’20 is using her honors history thesis to explore how college’s founding narratives affect the college today. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

She’s asking questions such as, “How do we talk about this history on campus? What is the consensus about talking about this history in a different way? Do people think it’s impacting their experience here?” And, if so, “positively or negatively?”

From her perspective as an interested alumna, Kristen Doerer sees value in Bates faculty and students continuing their exploration of the college’s founding connection to the American slave economy.

“It says that this institution isn’t afraid to take on hard topics and study, examine, and discuss them.”